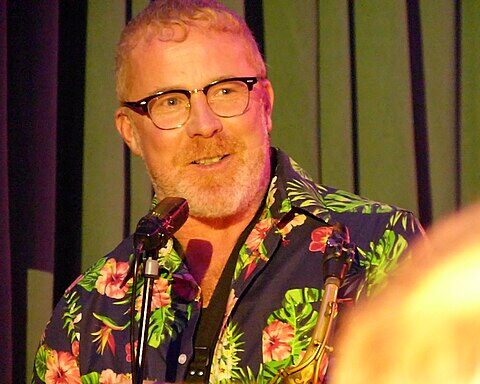

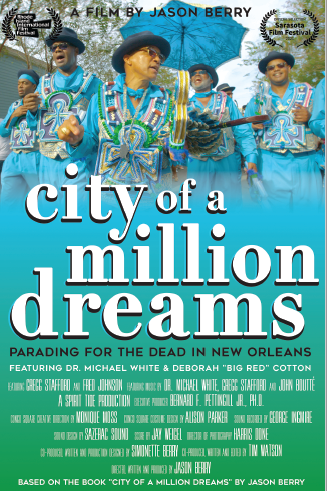

New Orleans native JJA author and documentary filmmaker Jason Berry speaks about

photo by Kathy Anderson

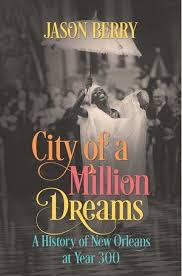

City of a Million Dreams: Parading for the Dead in New Orleans, released in 2021, his similarly titled book of 2018, challenges of filming, funding and promoting a jazz film in the age of Covid, and the current state of journalism in his home town.

LLF: For those who enjoyed your 2018 book City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at 300, what expectations should they have regarding the documentary of the same name?

JB: The book is a character-driven history covering 300 years, arguing that the city’s personality has been shaped by a long clash between a culture of spectacle and a city of laws, long anchored in white supremacy.

Burial traditions are a thematic thread. I could not do justice to the many eras and episodes across three centuries in a 90-minute film, but the dramatization of Congo Square depicting the dances of enslaved Africans in

swirling rings and burial choreographies to the ancestors is a major sequence in the film, building off several episodes in the book.

The first funeral with music I could document was the 1789 procession for Carlos III, the King of Spain; news of his death reached Nueva Orleans [the city by then had become a Spanish property] several months after the fact. I wanted to do a dramatization of that event but couldn’t raise the money. The book is a thorough, highly readable history; the film takes a more telescopic slant with Dr. Michael White, the clarinetist, and second line blogger Deb “Big Red” Cotton as the navigational figures.

LLF: What experiences, personal and professional, prepared you to create this documentary?

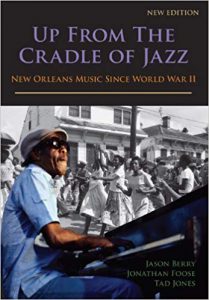

JB: I began following jazz funerals in the 1980s as a freelance writer for alternative weeklies and the city magazine in New Orleans. In 1986 I published Up From the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II with two colleagues, and over the next ten years or so, in going to wakes and funerals with music, I took a cue from

several New Orleans Style players – I use that term instead of “traditional jazzmen,” the term that was coined by the early jazz historian William Russell.

Dr. Michael White, trumpeter Gregg Stafford and older figures like guitarist Danny Barker, Olympia Brass Band leader Harold “Duke” Dejan (alto sax) and the Olympia trumpeter Milton Batiste — two generations of leading jazzmen bemoaned the impact of the crack epidemic on the burial parades. [They talked of] second liners, street dancers, tromping on cars; spewing beer on limos and coffins; brandishing and sometimes shooting off guns. The music by younger bands, not in traditional uniforms, was changing in ways these guys did not like. This was a chasm in the Black musical community. In such a beautiful tradition of ennobling the dead, that jagged fault line between continuity and change got me thinking about the funerals as a mirror on life and history.

In 1996, I landed Ford Foundation support for a video oral history project with the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane to film interviews and several funerals. It ran over two years. That’s how the book and companion film got started. I never imagined it would take 25 years but I had periods away for other work.

LLF: Who are the people (and institutions if applicable) who supported you during the project?

JB: The Ford Foundation provided initial support in the late 1990s. I received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2001 for research on the book. Hurricane Katrina upended the original production plan when Michael White lost his house. I filmed him returning in October 2005, a heartbreaking experience that comes midway through the film.

It took several years for Michael to regroup, a stretch in which I was doing investigative reporting (two books and a film, Vows of Silence) on the Catholic Church crisis. Finally in 2016 I began fundraising to get the [New Orleans] film back into gear. The Davis Dauray Family Foundation in San Francisco was a major supporter. Michael Arata, a New Orleans actor and attorney, provided major help in that phase. We had a number of fundraisers, with support from the New Orleans jazz and Heritage Foundation; the Cahn Family Fund; the Chase Family Foundation; a range of personal donors, a Kickstarter and timely help from Harry Shearer, James Carville and Dennis Vitrella.

The pivotal shift came in 2018 when Bernard “Biff” Pettingill, a friend since we went to Jesuit High School, saw the work in progress and provided substantial support, coming on board as Executive Producer. Independent documentaries typically rely on a combination of fundraising and grants with a fiscal sponsor approved for 501 [c] 3 donations, and private investors. I should also mention the Office of Louisiana Economic Development, through the film tax credit program, for crucial back end support.

LLF: On a personal note, do your final wishes include a jazz funeral (mine do) and who are you hoping will show up?

JB: I would naturally like to have a jazz sendoff. I hope that the city will withstand the ravages of climate change and sea-rise such that enough of the people I love will be around to say, “The boy did all right.”

LLF: How has the covid pandemic affected this project?

JB: We lost roughly a year of work.

LLF: We’ve seen confederate monuments fall and jazz endure. What cultural changes do you foresee for New Orleans in the future?

JB: The city still has no monumental sculpture underway to replace the statue at the circle long named for Robert E. Lee. A commission on changing street names from segregationists and slaveholders is underway with some encouraging results, offset by a myopia that a younger version of me would be railing against if time availed.

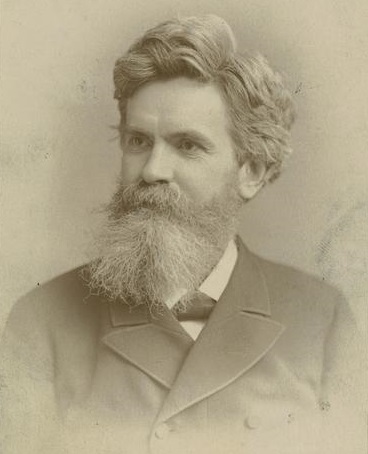

I did an op-ed suggesting a statue for George Washington Cable, the city’s great 19th century novelist

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

and civil rights prophet who was driven out by hostile whites and you could hear a great sound of yawning. I do love this place but it is a break your heart town too.

LLF: Off topic, but do you see a future for its newspapers in this difficult time for print industry?

JB: That’s one tough question.

The Times-Picayune/The Advocate is holding its own, good local news, and a recent $1 million Ford Foundation grant to further their investigative reporting. The daily owns the weekly Gambit, which is unfortunate as we need alternative voices, but Gambit delivers pretty well though with less editorial space than in years past. New Orleans Magazine is a food magazine in favor of Confederate monuments.

Here in the city where jazz began we have no full-time jazz critic. Keith Spera at the TP is an excellent music writer, but he covers everything from hip-hop to rock to concerts back again to jazz. There is no daily print listing of all the clubs and movie theaters. Offbeat, the music monthly, does digital and print listings, which is fine, but not broad-scope. Still, it’s the only place with regular CD and music reviews. The digital revolution kneecapped print media. There are so many unwritten stories about the music culture, yet I guess that’s true in many other cities. Wish I had an answer.

LLF: How can your fellow JJA members and the public see the documentary?

JB: Covid created a huge bottle-neck in films seeking venues at the film festivals. Getting an independent film before live audiences is a challenge. We’ve been fortunate in having five festivals feature the documentary since May: Sarasota, Flickers’ Rhode Island, Martha’s Vineyard African American, Heartland International in Indianapolis and the New Orleans Film Festival, which we headlined.

The website is posting the list of upcoming screenings with a link for folks to request a screening. We’re experimenting with small-audience Zoom screenings, outside of the festivals, many of which stream on their websites for a given window. We have college screenings in early 2022 at Tulane, Loyola New Orleans and Fairfield University thus far, with others in the offing.

We can send a link for JJA members who have review outlets or want to line up a screening. Email info@jasonberryauthor.com.

LLF: What’s next for you personally and professionally?

JB: Getting this film to market takes up a great deal of time. I am working on another book and thinking about another film. Of those, prudence dictates I say no more.