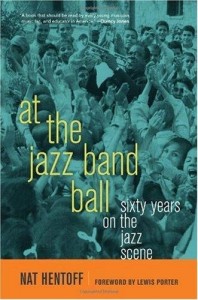

At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years on the Jazz Scene

At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years on the Jazz Scene

By Nat Hentoff

(Foreword by Lewis Porter)

University of California Press, 2010, 246 pp., $27.50 hardcover

Nat Hentoff has two passions, jazz and the U.S. Constitution. That these are not disparate interests he clarifies by quoting Max Roach: “What we do musically as we tell our stories is based on each individual’s listening intently to one another, and thereby creating a whole experience that has its own identity. Isn’t that how we and the Constitution are supposed to work together?” Some readers of Hentoff’s jazz writings may not be aware that he is also an authority on the First Amendment, has published books on the subject, and that his “day job” is “checking the pulse of the Constitution” — in other words, chasing down abuses of it and citing them in print.

Stanley Dance expressed to me three decades ago his conviction that it was important to gather in book form a writer’s previously published essays, reviews and profiles of musicians. Over the years we have seen many such jazz-themed compilations, either under individual bylines or as anthologies, and we are the richer for it. Hentoff’s At the Jazz Band Ball includes 60 pieces from his JazzTimes and Wall Street Journal columns and his reporting for several other periodicals, all appearing in the years 2004-2009, plus several transcribed TV interviews. It’s a welcome addition to similar volumes by Whitney Balliett, Stanley Crouch, Francis Davis, Ralph Ellison, Otis Ferguson, Gary Giddins, Larry Kart, Philip Larkin, Dan Morgenstern, Doug Ramsey, Martin Williams and others, including, I add in all modesty, yours truly. Incidentally, this is Hentoff’s 35th book (five of which he co-authored or edited).

Of presently active jazz writers, Hentoff is nearly unique in the extent of his reach across the decades and his ability to cite acquaintance — sometimes strong friendship — with musicians of different eras and styles. Considering himself a “chronicler” of the jazz scene rather than a critic of “form,” he has concentrated on looking into musicians’ lives and delineating how, à la Charlie Parker’s dictum, they play those lives in their music. He rarely offers analyses of their playing, “emphasizing the person rather than the process,” although he is quick to praise the talents of musicians on the bandstand and in their recorded efforts, here and there noting that this or that important musician has been woefully neglected (for example, pianist Paul Bley).

So personal is Hentoff’s writing style, he makes us feel that we are on intimate terms with the likes of Duke Ellington (clearly his main man), Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ruby Braff, Dizzy Gillespie, Phil Woods, Clark Terry, Marian McPartland, John Coltrane, such younger artists as singer Catherine Russell and violinist Aaron Weinstein, and even a teenage student saxophonist, the JJA’s Mikayla Gilbreath.

Frequently, Hentoff expatiates upon some very important problems besetting the jazz world. Chief among these is his concern over how to bring jazz into the mainstream of public education so that grade school and secondary students will come to appreciate not only the music itself, but the significance of the jazz idiom in our culture, history and society. Two lengthy interviews — 17 and 14 pages respectively — with Jon Faddis and Ron Carter explore the ins and (mostly) outs of jazz’s presence in the schools. The theme of jazz education crops up in many of the profiles as well.

Another concern of Hentoff’s is the need to recognize “the vital creative force of women in jazz — instrumentalists, not only singers.” He gives expression to this commitment in his profiles of saxophonist Hailey Niswanger and pianist Anat Fort, and in a substantial survey that appeared in the summer 2008 issue of American Legacy magazine, “The Ladies Who Swung the Band.” Commencing with accounts of the 1940s International Sweethearts of Rhythym and other early all-women bands, he goes on to praise trumpeter Valaida Snow, who was active into the 1950s, reed player Anat Cohen, drummer Sylvia Cuenca and flutist Nicole Mitchell. Of Diva, Hentoff avers, “If there were still big-band competitions . . . these women would swing a lot of the remaining bands out of the place.” He quotes writer Lara Pellegrinelli: “Virtually none of the top mainstream bands — the Smithsonian Masterworks Orchestra, the ghost bands of Count Basie or Duke Ellington . . . currently employ any female players.” Hentoff praises Wynton Marsalis as “a teacher and leading spokesman for the jazz community,” but points out that “among women musicians he has also long been known as never having had a full-time female member of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra.”

Hentoff pulls no punches, as in his somewhat overheated denial of the jazz credentials of Diana Krall and Jane Monheit. More welcome, to this reader, are his citing of the “educational malpractice” of the late International Association for Jazz Education (IAJE) for overlooking “Sonny LaRosa’s ‘America’s Youngest Jazz Band, Featuring Musicians Ages 6 to 12’” and his urging “the record companies profiting from the very welcome flood of jazz reissues” to “become important contributors” to the Jazz Foundation of America, which provides medical care and other financial assistance for ill and destitute musicians.

Much like the musicians he loves and admires and who have given him direction in his life, Nat Hentoff has his own voice. It is warmly personal, authoritative, sometimes curmudgeonly. If at times he comes across as unbending in his certitudes, he has, now in his mid-80s, paid some considerable dues and doesn’t hesitate to let you know it. As well he has a right to, considering that his ear has been tuned to this music and its makers for more than seven decades.

In an epilogue, “My Life Lessons,” Hentoff speaks of periods of suffering personal depression, “bottomless black sites [that] can’t be imagined by anyone lucky enough never to have experienced them.” He has found relief in two ways, one, by recalling “the stories of . . . jazz musicians who so unyieldingly insisted on listening to their own drums,” and, two, in the music itself. At the close of his interview with Ron Carter, Nat sums up what jazz has meant to him: “In my day job I’ve met all kinds of people, supreme court [sic] justices, defense lawyers, whatever, but the people I’ve learned most from, not only in their music, and that’s a lot, but from themselves, are musicians.” Amen.

Wow. Great review. It makes me want to buy the book. Thanks to Royal Stokes.

Wonderful review by W. Royal Stokes. I only recently found out about Mr. Hentoff's book, and I am absolutely amazed and honored that I was mentioned in it. I have ordered a copy and can't wait to receive it.

Reading the book now, My father and uncles also attended Boston Latin School at the time Nat Hentoff was there, and spoke often of the experience. As a jazz musician I appreciate the fact that he reports from first-hand experience of the times and the players, and as a son, I enjoy the little bit of my father's Boston that he so evocatively conveys. -- Tony Corman