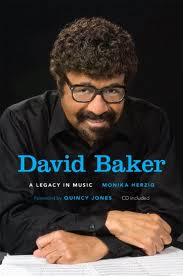

David Baker, A Legacy in Music

By Monika Herzig, with contributions by Nathan Davis, JB Dyas, John Edward Hasse, Willard Jenkins, Lissa May, Brent Wallarab, and David Ward-Steinman. Foreword by Quincy Jones

Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2011; 448 pps; $29.95 hardcover

While the word does not appear in any of its more than 400 pages, this attractive volume clearly belongs to the academic literary genre known by the German term “Festschrift.” As such, it implies (normally just one) volume celebrating the life and achievements of a highly respected academic. The contributors to the volume are usually the honoree’s colleagues and/or former students.

In this instance, the volume celebrates Professor David Baker of the prestigious Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University (IU) on his 80th birthday (December 21, 1931). All contributors — with the exception of our own Willard Jenkins and Dr. Nathan Davis, director of the Jazz Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh — have a connection with IU in one way or another.

Born in Germany, Dr. Herzig came to the United States in 1988 and eventually received her doctorate in Music Education and Jazz Studies at Indiana University. She is a jazz pianist and composer, a former student of Baker and now his colleague on the IU faculty. Dyas also has his PhD degree in Music Education from Indiana; Hasse has his doctorate in Ethnomusicology from IU; May received all her degrees from Indiana and is an associate professor in her alma mater’s music school; Wallarab is also on the music faculty at Indiana, and Ward-Steinman is an adjunct professor in the Jacobs School of Music. Even Quincy Jones has an honorary doctorate from IU and gave the commencement address there last year.

As a former member of IU’s faculty myself (now Professor Emeritus), I got to know David Baker as a friendly acquaintance. We started at Indiana in the very same year, 1966, he in the School of Music and I in the College of Arts and Sciences. We once served together on a large pan-university committee, and David kindly allowed me to sit in on his popular jazz history class in 1987. (It’s not often that one faculty member has an opportunity to see another faculty member in class on an almost daily basis, and I have to say that that experience was a distinct pleasure for me.) I also had occasion to see Baker in action many times on the performance stage, both in the Musical Arts Center on campus and at the nearby club known as Bear‘s Place. I know a number of his former students who are now professional musicians. I have also run into David many times since retiring, most recently when he was in New Orleans as an NEA Jazz Master to deliver a lecture at Loyola University last year.

Under the circumstances, Howard Mandel rightly warned me ”in the interest of journalistic integrity re the JJA” to not hesitate to point out any of the book’s “flaws or limitations” (if they existed) in my review. I have attempted to take his advice into careful consideration as I contemplated that which follows.

The volume is divided into nine chapters plus six appendixes; a bibliography of Baker’s written works; a Baker discography, and a selected list of publications about David Baker. Also included in the book is a CD with 11 tracks of selected Baker compositions and performances by him on both trombone and cello.

Quincy Jones notes in his foreword that Baker, then a trombonist in his band that toured Europe in 1960, “could really play.” He goes on to say, “As my success grew scoring films, arranging, and producing, I tempted David to come and join me in Hollywood. But his dedication to teaching, and to the program he built at Indiana University, was stronger than the promise of riches and fame.” That pretty much captures the spirit of the man represented in this book. As JB Dyas observes later (Chapter 4, “Defining Jazz Education”), “David is an eminent performer, composer, arranger, bandleader, and conductor — but I believe he has made his greatest contributions as a pedagogue.” Indeed, those contributors who studied with him, beginning with the comments of Herzig in her preface, emphasize Baker’s high standards as a teacher as well as the high expectations he has for his students, who have included Randy Brecker, Jamey Aebersold, Chris Botti, Jim Beard, John Clayton, Shawn Pelton, Herzig herself and on and on. But the aim of the Baker Festschrift is to give as complete a picture as possible of the many dimensions of this remarkable man.

In Chapter One, May surveys Baker’s youth in Indianapolis, where he grew up, and his relationship with peers such as fellow trombonists Slide Hampton and J. J. Johnson.

Herzig outlines his early career in Chapter Two, including his winning Down Beat’s New Star Award in 1962, attending Indiana University (MA, 1954), his first real jazz education at the prestigious Lenox School of Jazz, his early compositions and performing with the George Russell Sextet and his first teaching position at Lincoln University in Missouri.

The turning point in Baker’s career — the 1953 auto accident that eventually caused him to give up the trombone and turn to the cello and jazz education — is covered by Herzig and Davis in Chapter Three (“New Beginnings”).

JB Dyas, vice president of education for the Thelonius Monk Institute, discusses thoroughly and in considerable detail Baker’s approach to jazz education in Chapter Four.

In Chapter Five Brent Wallarab, trombonist, arranger and co-leader of the Buselli-Wallarab big band, joins with Herzig in evaluating Baker’s contributions as a composer and arranger –especially as they are reflected in his “21st Century Bebop Band.” I had occasion to watch this band, with its unusual instrumentation — cello, tuba, flute (played so well by David’s wife Lida), piano, bass and drums — evolve in the 1980s.

Composer David Ward-Steinman discusses the scope and details of some of Baker’s compositions, estimated to be more than 2,000 in all, in Chapter Six (“The Composer”).

John Hasse, curator of American Music at the Smithsonian, analyzes in detail Baker’s intimate relationship to that institution, especially the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra and the new Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology (just released in the spring of last year). Chapter Seven is exceptionally thorough and the longest in the book.

Chapter Eight (“Social Engagement“) focuses on David Baker’s service to his profession by addressing his relationship to the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Council on the Arts, the late National Jazz Service Organization, the late National Association of Jazz Educators and its successor, the late International Association for Jazz Education. Jenkins succeeds in demonstrating Baker’s devoted and tireless service to jazz.

In a “Coda” (Chapter Nine), Herzig offers a most interesting analysis of the state and future of jazz education.

Finally, just to mention the appendixes: A (“List of Compositions”), B (“Awards and Honors”), C (“Service”), D (“Performing Experience”), E (“Teaching”) and F (“Professional Societies and Organizations, Past and Present”). I would have liked to see a list of Baker’s best known students (especially those who are now performing) as well, though I understand the difficulties of preparing such a list.

Jazz education has come a long way since its formal beginning at (then) North Texas State in 1947. As we all know, countless institutions of higher education now offer jazz courses and/or degrees, and several centers of excellence now exist, Indiana University certainly among them. Maybe I’m overly sensitive since I live in a city where two fine programs in jazz education can be found, at Loyola University and the University of New Orleans, as well as the first-rate program on the secondary school level at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts. Yet, while fully realizing this volume is intended to focus on David Baker, Herzig’s presentation rather gave me the impression that IU is at the center of the jazz ed universe.

I give warm thanks, in conclusion, to Ms. Herzig for putting together the Baker Festschrift. Unlike many other examples of the genre, this one has real substance. It is a fine tribute to this extraordinary man and a valuable contribution to the history of jazz for the last half-century. I recommend it highly.

Love David, but it's Festschrift, accurate in final graph, but wrong in headline. We're supposed to be pros, so please correct.

From and old editor....