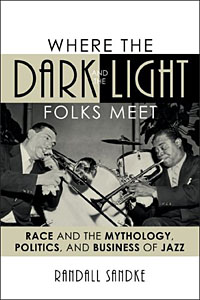

Where the Dark and the Light Folks Meet: Race and the Mythology, Politics and Business of Jazz

Where the Dark and the Light Folks Meet: Race and the Mythology, Politics and Business of Jazz

By Randall Sandke (Foreword by Ed Berger)

Scarecrow Press, 2010, 275 pp., 246 pp., $40.00, hardcover

Review by Howard Mandel

Randall Sandke, known to jazz aficionados as a trumpeter and composer, has written a provocative, exhaustively researched and ambitiously analytical book about a significant and endlessly complicated topic: race and jazz. A third-rail issue if ever there was one, the integration of America’s 20th and now 21st century culture with our continuing sociological and ethnographic history involves compelling material, presenting many highly sensitive issues to participants of any and all U.S. arts.

Unfortunately, Sandke’s entire book seems aimed to support an agenda rather than explore a thesis or celebrate the achievements jazz musicians of every stripe have made to overcome social prejudice. His argument is with history and myth – implacable adversaries — and his perspective nowhere near as comprehensive or unclouded by personal bias as he believes it to be.

As a musician, Sandke is thoroughly informed and inspired by tradition, with bracingly original ideas about modernity and creativity. Though regarded as a specialist in early repertoire, he has performed in every jazz sub-style, and recorded examples of his own “metatonal” harmonic theory. Presumably he’s had many experiences working with black and white, yellow and brown musicians worldwide. However, here he writes less about the triumphs, collaborations and spaces shared by African-, Hispanic-, Caribbean- and Euro-American individuals so much as detail what he considers to be the romanticization and politicization of black musicians’ contributions in comparison to what he thinks is the slighting of Caucasians’ deep involvement since the beginning in the creation and dissemination of the bluesy, swinging, hot and cool music.

While acknowledging that the most inspired, innovative and influential jazz musicians have overwhelmingly been black, Sandke insists that white jazz composers, players, bandleaders and businessmen – even the famous ones who made fortunes — have consistently been denied appropriate status in the music. He shrugs off the obvious: that white popularizers from Paul Whiteman through Kenny G have been rewarded with promotion, acceptance and wealth disproportionate to the value of many other musicians’ creativity.

Sandke nods to but doesn’t factor into his discussion the reality that for most of the past hundred years and maybe still, black musicians in America have operated at a considerable disadvantage, and that the work by everyone from the authors of Jazzmen and Marshall Stearns through Gary Giddins (and perhaps – due self-recognition – myself) has been intended at least in part as a corrective. Without the efforts of white writers who Sandke accuses of having been overly laudatory to black musicians – and also the enthusiasm of listeners of all stripes – the music of Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and the other greats may never have been heard by the majority of white America at all.

“Does jazz represent the expression of a distinct and independent African-American culture, isolated by its long history of slavery, segregation, and discrimination?” Sandke asks at his book’s outset. “Or, even when produced by African-Americans (or anyone else for that matter) is it more properly understood as the juncture of a wide variety of influences under the broader umbrella of American and indeed world culture?” Typifying the first notion as “exclusionary” and the second as “inclusionary,” the author launches himself into a false binary. In the vast sphere of contemporary musical activity that should all fall under the umbrella term “jazz” it’s not too difficult to entertain both depictions: jazz as derived from specifically African-American culture, but a sponge for every type of influence, processed through myriad unique and personal lenses, some of them belonging to white practitioners (and also brown, red, yellow, female as well as male and gltb ones). That is a perspective jazz commentators from Amiri Baraka through Wynton Marsalis and maybe including Sandke himself might agree on.

“Through the dark days of legalized segregation and on into the civil rights era, jazz shone as a beacon for achieving interracial respect and understanding.” Sandke poses this as an image of a departed Golden Age, though a closer look at evidence brought to light by other tomes makes the claim dubious. “It seemed as if the dream of a color-blind society was within reach in the jazz world, where musicians were judged on merit and not on skin color. Status in the jazz world was conferred on the basis of real achievement and not some artificial standard of rank or pedigree, and the music itself was infused with honesty and integrity.” A little later, he adds: “I want to see music judged on its own terms free of external considerations.” Well, isn’t that a nice thought. Dream on, pilgrim, dream on.

But rather than consider that the status of musicians in the jazz world may not be free of external circumstances, and that those circumstances during at least the first half-century of jazz explicitly favored musicians with white skins who appealed often exclusively to white audiences, Sandke cites as villains who demonized white jazzers the jazz press and people he presents as self-serving, two-faced producer-propagandists (Alan Lomax, John Hammond) and parties he identifies with the Depression Era left-leaning “Popular Front”: Ralph Ellison, Albert Murray, Langston Hughes, Milt Gabler, Norman Granz, Barney Josephson and Max Gordon among them. He sees the culmination of this distorted view in the rise of Wynton Marsalis and establishment of Jazz At Lincoln Center. According to the author, these jazz supporters were “activists,” upholding the primacy and purity of African-American jazz to advance the social imperative of civil rights regardless of aesthetic realities of “merit.”

Sandke’s contention is that a vast, powerful cadre of commentators spread the view that being black was essential to being a jazz musician. He’s right that this belief was often expressed, and I’d say right that it has often been exaggerated, perhaps even to the detriment of white musicians of merit. But he is severely mistaken to think the press or any other clique has had the power to force such a debatable notion on the greater public. The press and “activists” Sandke deplores have never been able to limit the success of white popularizers or genuinely artistic white musicians. Seldom have they tried.

Have Bix, Eddie Condon and the Austin High Gang, white swing band stars and soloists, jazz singers starting with black-faced Sophie Tucker and Al Jolson (later Crosby, Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Rosemary Clooney), Lennie Tristano and his acolytes, Stan Kenton and his sidemen, guitarists from Les Paul through Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis and Tal Farlow to Joe Pass and Jim Hall, vibist Red Norvo, pianists George Shearing, Marian McPartland (the rare woman to maintain a lengthy jazz career) and Bill Evans, bassists Scott LaFaro, Red Mitchell, Niels-Henning Orsted Pederson and Jaco Pastorius, saxophonists from Bud Freeman through Steve Lacy and Michael Brecker, trumpeters such as Harry James, Chet Baker and Maynard Ferguson, trombonists including Bill Watrous, Frank Rosalino and Roswell Rudd, drummers as different as Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich and Paul Motian, composer-arrangers Claude Thornhill, Gil Evans, Nelson Riddle, Bob Brookmeyer and Bill Holman been overlooked or underrated? In favor of whom? Have Al Hirt, Pete Fountain, Herb Alpert, Harry Connick and Jamie Cullum not prospered? Yes, so have Oscar Peterson, Quincy Jones and Miles Davis. Have unworthy musicians “of color” been forced on the larger culture? Are their reputations sustained by hype? Compare and contrast.

Since the triumph of the civil rights movement in the 1960s and rise of fusion circa 1970 (which Sandke ignores) the place where light and dark folks, or at least their ideas, genuinely meet has greatly changed. Jazz journalists, scholars and listeners who’ve emerged over the past 40 years seem to generally have more nuanced views of who’s black, who’s white, who’s great, who’s not than previous generations did. Marsalis does get a lion’s share of press attention and public funding – he’s also lived up to the responsibilities of all that.

Today’s biggest jazz stars and/or most respected improvising artists include Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea and Brad Mehldau, Mike Mainieri, Joey Defrancesco, Pat Metheny, John Pizzarelli, John McLaughlin and John Scofield, Charlie Haden, Dave Holland, John Patitucci and Gary Peacock, Chris Botti and Dave Douglas, Jay (Spyro Gyra) Beckenstein, Dave Liebman and Joe Lovano, Steve Gadd, Dave Weckl and Matt Wilson, Medeski, Martin and Wood, the Bad Plus, composer/bandleaders Carla Bley, Maria Schneider and Darcy James Argue – need I go on? Up and coming there’s a generation of jazz stars with highly diverse ethnic/racial backgrounds — Joshua Redman, Esperanza Spalding, Rudresh Mahanthappa, Vijay Iyer, Norah Jones, Miguel Zenon, Dave Fiuczynski . . .Where do they fit on a color line? Who cares? Why does it matter?

For an in-depth study of the complicated realities regarding jazz and race, there is a worthy bookshelf. On it, find Cats of Every Color by Gene Lees; Subversive Sounds: Race and the Birth of Jazz in New Orleans by Charles Hersch; The Color of Jazz: Race and Representation in Postwar American Culture by Jon Panish; Come In and Hear the Truth: Jazz and Race on 52nd Street by Patrick Burke and Lost Chords by Richard Sudhalter. Each of these, and other books with similar focus, contribute to a richer understanding of a multi-faceted topic. Sandke’s volume may belong on that shelf, too, representing the yearnings of a man who is primarily a musician seeking attention for musicians he admires who he feels have been thwarted due to unfair perspectives on their chosen field. I find little in his selective evidence and muddled analysis to convince me that past perspectives have been overwhelmingly unfair. But Where The Dark and Light Folks Meet has accomplished one of its author’s possibly unintended, certainly unstated goals. Reading it has compelled me to return to Randall Sandke’s recordings to listen.

A very fair assessment of an important, if somewhat troublesome, book, Howard.

Howard:

Great analysis. I've always thought the claim of "reverse racism" in jazz was weak and even offensive. However, Sandke is entitled to his opinion and perhaps should be commended for defending a stance that might not be so popular....or maybe it is.

Look at the cover of any new jazz magazine and you'll find a white face. Jazz is the history of the triumph of a race--the black race--and of the whites who gave them a boost here and there. Not to say it's all for them: we all benefit, perpetuating freedom through free music.

What happened to the days when race didn't matter? The only thing that mattered was if you could no mather what color your skin is. That's how it was for me in the 60's & 70's.

As I understand it, the whole issue of "race" was never an issue for humanity until the Atlantic slave trade needed something to justify itself at which time an entire philosophical, theological and proto- anthropological infrastructure organized itself (for pay) to provide intellectual cover.

Other "race" obsessed people included the Nazis and the US and UK elites who supported them, people like Henry Ford, Hearst, and Rockefeller and their modern descendants who are worried about population growth (the population of people they classify as non- white that is.)

"Race" in my opinion is only an important discussion in so far as we still have to digest and hopefully some day heal the legacy of that horror.

The practice of categorizing people into white and black is a slavery remnant and does nothing to explain

anything about OUR music. That said, people with dark skins have been both mistreated and fetishized as a result of their appearance. To me that's a subject for abnormal psychology and the question of which "race" deserves credit for what and who got the better deal is laughable.

An important topic that black folks and musicians don't always enjoy talking about. And one that white musicians often feel misrepresented. Apart from regular consideration of musical kinship and -yes- good old fashioned friendship, for anyone to say that white musicians are fairly represented in the overall jazz"market" (or lack thereof) is to live in a distant world where I myself would like to live.

I really have no idea where Gordon Marshall buys his magazines, but let's refresh his memories, I'm looking at some of the most recent cover of Jazztimes in 2010 and what do I see: Rollins, Miles, Lenny White in the last four covers (sorry but I can't find older magazines right now).

So, please, let's discuss race in music, but let's make fairness an all-important first step. That's where it should start. Fairness for each and everyone.

My book does in fact document over a century of inter-racial contact and collaboration in jazz, and much more thoroughly than any other. If you want to call that a "celebration" that's fine with me. Howard's characterization of my book is in fact a caricature. The way he describes it, I wouldn't want to read it either, much less spend ten years of research producing it. He accuses me of being a Johnny-one-note harping on reverse racism when in fact the book is concerned with a whole range of topics not typically addressed in other jazz books.

I will post a more thorough rejoinder to Howard's irresponsible and distorted review soon. In the meantime, perhaps someone should get him a more focused pair of reading glasses for Christmas.

As I told Randy when he posted this comment on my blog (artsjournal.com/jazzbeyondjazz) I did get new glasses while I was reading his book, to make sure I was seeing clearly. Anyone who thinks I've mischaracterized his book should definitely read it for themselves.

I find it very disheartening that the president of the JJA is so blithe about dismissing the notion that music should or even can be judged on its own terms. Are you admitting that you listen differently to someone’s music based on race, gender, class, or whatever? Musicians know that they cannot achieve perfection but that doesn’t keep them from striving for it. A critic perhaps knows he or she can never be truly objective, but shouldn’t that still be their ultimate goal? I guess when we listen to Bach we’re supposed to be thinking about all the poor serfs toiling in the fields and not the way his brilliant manipulation of pitches and rhythms speaks to the soul. Thanks for the insight into why so much current jazz criticism is a meaningless waste of time (and I’m not being sarcastic here--just honest).

This is a rather biased review. I suggest those interested-- read the book, rather than rely on this holier than thou critic.

Holler-than-thou is a useful and original descriptive. Charges of bias demand substantiation, otherwise they're just slander. I have a perspective on Sandke's book, but no prejudice against him.

In a simple frame, Jazz is as Black as gangster rap. Readily accessible evidence isolating the latter genre to origins amongst America's Black "lower" classes insulates this claim of origin from much argument. As Jazz was in the cauldron of it's birth, I gather the color line was quite distinct. Still, once a language is fully emerged, many may learn to speak it. Look how well so many of us African Americans do with English.. ironically, and for many of us, our only language. Well, beyond Jazz that is :-/

I'd say that jazz is much Blacker than gangster rap. Gangster rap had much more support from the white music industry in its earliest years than jazz ever did, at least in its first decade and a half, depending on how one dates it. I might even suggest that Gangster rap was, as a commercial phenomenon, a white enterprise using Black musicians. Chuck D scared the industry too much.

Yes, I have decided to begin a blog.

Not so many entries there, but thousands of hits already, astonishingly.

I am finding that the fewer words I write, the more meaningful become the words I do write.

It is senseless to purge an entire roster of reasons for anything anymore, because that is basically a means to mirroring one's personality.

Expressing oneself in a creative way is one thing. Responding...reacting...is another.

So many questions I have asked, I already had the answer to, right there staring me in the face.

By the way...somewhere along the line I passed by a quote by Marshall McLuhan, which goes something like this: having a perspective is fine as long it does not become or is meant to be the truth.

"In the Greek myth, Procrustes was a son of Poseidon with a stronghold on Mount Korydallos, on the sacred way between Athens and Eleusis. There, he had an iron bed in which he invited every passer-by to spend the night, and where he set to work on them with his smith's hammer, to stretch them to fit." Wikipedia

The creation myth of jazz is as follows: 1) it is a music developed in New Orleans by African Americans. 2) it developed from a peculiarly black ethos based on African traditions in which group identity was paramount. 3) This group ethos is reflected in the musical tradition of group improvisation, and it continues to bear a strong influence on jazz even a century later 4) White musicians took to the music very quickly, and the musical result was an unsatisfactory melange based on aesthetic misunderstandings. 5) The white musicians gained fame and financial success at the expense of its black creators. 6) White businessmen took advantage of black jazz musicians for their own financial benefit. 7) Racism has guided the development of the music in small and big ways.

All of these points are, at the least, worth considering and I believe that in general they are true. Unfortunately, jazz critics and historians have willfully ignored or reinterpreted any facts or events that contradict any interpretation of jazz that point to a more nuanced view of black culture and American life. Sometimes it is because they cited secondary sources that have proven to be without merit (see Randy's section on the music in Congo Square) or rely on self-proclaimed experts like Gunther Schuller who famously put African music (as interpreted by A. M. Jones) into his own Procrustean bed so it fit his own idea of New Orleans jazz. Jazz historians tend to ignore the greater American culture that has always existed around black culture. The tendency is to place musical innovations within black culture that really occurred in a broader American culture first. In some instances, the real innovators were whites, but over and over black musicians succeeded in elevating it into a more powerful artistic statement. The tendency is to denigrate music made by whites or speak of their music in a patronizing fashion. Often forgotten is that the proper critical response is to evaluate the music with different standards than one would use with contemporaneous jazz. Jean Goldkette isn't Louis Armstrong, but so what!

Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s a reaction has occurred among several white critics and jazz musicians that is just as disturbing as the Procrustean bed of black essentialists that they wish to expose. These writers begin with a praiseworthy goal: to bring back into prominence the music of brilliant white musicians whose music stopped getting the attention it deserves and to emphasize the multiculturalism of American society. This group of musicians and writers oversteps itself and wishes to overturn the entire jazz pantheon. James Lincoln Collier, please take a bow! Now that the jazz world has in Wynton Marsalis a tastemaker and powerhouse with dark skin, he becomes the embodiment of a situation in which theoretically speaking, the tables could be turned against white musicians for good. As I point out in my book (written in the 1990s when Jazz at Lincoln Center was still new), at a time when the NY Philharmonic had zero blacks in it and very few Asians, Wynton chose to make his band mostly black. Is this bad? Speaking as both a musician and scholar, I, for one, don't care who Marsalis wants to put in his orchestra, and I'm not sure how significant the black-to-white ratio is in this instance. [p. 10 in my book Jazz in Black and White:] "How obligated is Marsalis to give a race-neutral program? Should he be required to follow standards of hiring adopted by trade unions? Should these standards be required by the sponsors of all cultural events? Should James Brown have been required to hire Korean musicians before permitting him to perform at the Apollo? Should the Juilliard String Quartet have been mandated to add an African-American cellist when their cellist retired from the group several years ago?"

So ends my diatribe of the day. I hope you get around to reading my books! (Jazz in Black and White: Race Culture and Identity in the Jazz Community, Salsa! The Rhythm of Latin Music, Cuban Musicians in the United States- Charley

well, I've only just begun reading Randy's book and think it's a much more honest appraisal than may be indicated by Howard's review - the problem is that Randy's argument is not either/or; he's accurately portraying the perceptions of a large part of the populace, and he's showing the reality for the vast majority of white jazz musicians, not the ones who appear on Downbeat's cover. For those of us below the upper tier, it;s a constant struggle to prove our "authenticity."

and just to add as a self plug, in addition to the above-named, I do believe that my jazz history That Devilin Tune was the first to really look at the black-white thing in perspective. While I admire Sudhalter's work on white musicians, my intention in Devilin Tune was to show, through the music and it manifestations, the true integration of jazz's history.

And lastly, let me say that the person who has written the best things on the parallel cultures of black and white Africa and the USA, is John Szwed. For these essays I recommend a collection of his called Crossovers.

let me please add one more thing, in anticipation of the comment above about the difference between perspective and truth - if Randy's perspective is that he personally has lost out because of certain kinds of reverse racism, than this IS truth, because he is absolutely correct (there is no other jazz player I know whose renown is in more inverse proportion to his genius then Randy). And this is significant; to quote Martin Luther King "I cannot be what I want to be until you are what YOU want to be,"

I agree with Allen (whose book That Devlin' Tune is an admirable and valuable alternative to the conventionally accepted jazz history narrative) that Randall Sandke is "accurately portraying the perceptions of a large part of the populace, and he’s showing the reality for the vast majority of white jazz musicians, not the ones who appear on Downbeat’s cover. " However, that perception is sadly skewed. It's unfortunate how racism in America doesn't just hurt people who aren't white, but regular ol' racism set up more intractable barriers to more musicians than "reverse racism" ever did.

It is a challenge to every musician -- to every artist -- to establish themselves/ourselves as legitimate, credible, "authentic." Musicians in jazz have always been able to do that with other musicians by demonstrating that they can play. That's the meritocracy that Sandke's book might have celebrated -- by its title, promises to concentrate on -- or explored more thoroughly if it didn't spend its words on denunciations of journalists and producers who supported black musicians they thought were artistically worthy and/or commercially viable in their careers.

"Renown in inverse proportion to genius" is rife in the history of jazz, cutting so far and deep across "race" lines as to render that kind of identity if not meaningless, not the A-one necessary principle, either. Who's "successful" in America depends on a lot more than race, right now as throughout American history. Commercial success and "renown" rests on such elements as artist-audience Identification, artist/business projections, art-work marketability/saleability as perceived by marketers and sales forces prevail to a far greater degree than the immediate OR enduring influence of a cadre of "activist" critics and scholars (though yes, their support can help). A musician like any artist is successful by dint of their individuality, taken whole. Personality, building relationships, presenting art that other people want to support -- these things all make a difference.

Allen's assertion that Sandke (and/or his book?) is valid because "he personally has lost out because of certain kinds of reverse racism, then this IS truth, because he is absolutely correct (there is no other jazz player I know whose renown is in more inverse proportion to his genius than Randy)" is debatable on two fronts. First, I can think off the top of my head of a couple dozen musicians -- of every ethnic background -- whose renown is as inversely proportionate to their genius as his. And secondly, considering the many other musicians with Sandke's ancestral background who have somehow been able to triumph over "reverse racism," it makes one wonder if Sandke's professional problems as a musician have something to do with personal attributes or the attractiveness of his music -- either way, something other than the color of his skin.