On Amazon, reviewers so far are unanimous in their five-star appraisal of Peter Pullman’s Wail: The Life of Bud Powell, and all they write is true. This book is impeccably researched, compassionate towards its deeply problematic subject without being mawkish or hagiographic, and multi-dimensional in its portraying of music, society and the lives of a distinctive coterie of difficult

people under considerable strain, some of them among the most gifted American artists of the 20th century.

Pullman is indeed a fine writer, economical and vivid, able to make the import of abstract music clear without using jargon or musical notation. He’s especially good when describing the late ’40s – early ’50s midtown Manhattan milieu which allowed bebop to come to prominence, almost despite itself and the musicians’ professional ambivalences, often expressed in very self-destructive behavior. Powell was plagued by those ills, in spades.

That the author can sustain his own patience and the reader’s concern for Powell is just short of miraculous. Although there are hints that the pianist might have suffered from the condition known today as autism, this diagnosis was evidently unknown in the ’40s, certainly not applied to anyone of Powell’s background, and Pullman doesn’t speculate (as I just have) about its possibility, either. Nonetheless, it is painful to read of the prodigy who had no life beyond his keyboard, who behaved with infantile resistance even to many of those who held his genius in high regard, and who was mercilessly abused by several people who got quite close to him. Which is not even to mention the invasive, mind-numbing “treatments” Powell endured from doctors and courts for virtually all his productive yet sadly attenuated life.

The best tribute I can make to Wail is to say it reawakens my interest in music I have somewhat taken for granted. Powell’s pianism, at its best characterized by speedy, graceful and long melody lines fed by spare yet propulsive comping remains to this day the model for straightahead mainstream jazz keyboardists, bearing a marked influence on Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea, just for starters. If Bud’s style has become foundational, we tend to forget its innovative qualities. But while reading this work, one will want to have the works of Powell as well as Kenny Clarke, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Monk, Mingus and Tatum at hand. The Complete Bud Powell on Verve, for which Pullman compiled a dozen interviews that set him up to pursue this longer project, is one vital companion piece; The Complete Bud Powell Blue Note and Roost Recordings 1949 – 1958 is another. But as the book unfolds you’ll find yourself reaching for Sonny Stitt sessions on Savoy and Prestige, Jazz at Massey Hall, and even Powell’s last, disastrous ESP-Disks. Pullman does an exemplary job of making this music live, usually with just a few words that convey his expert judgments.

Jazz aficionados may long for the return of the hothouse atmosphere of 52nd St., where Bud et al made their music a public art. Such a scene is unlikely to come again, but if it does we can hope it will be free of the corruption, bigotry, exploitation and disregard for creative genius which Powell experienced and Pullman describes. The book may help us avoid the return of such failures by the mental health care establishment, the police, club owners and record producers, fans, family and so-called friends by depicting what went wrong in Bud Powell’s life almost from his start. It’s disenheartning that such horrors should befall a person as sensitive and/or as troubled as Powell was; it’s pitiable, and maybe tragic. But with Wail, Peter Pullman has done a great service to many contingents of modern sophistication — not only jazz fans, and most especially the legacy of Bud Powell.

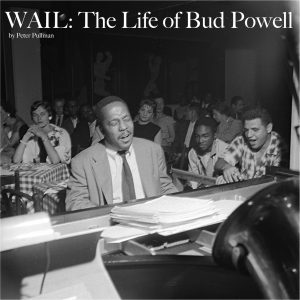

Just as a p.s.: Wail is currently available only as an e-book, and I found the format made close attention to Pullman’s detailed footnotes and endnotes problematic. Bookmarking and search functions make navigation available, but it’s a challenge to search out references in past pages when one is farther along in the tome. Also, I would have enjoyed seeing some of the photos Pullman refers to, which I suspect the self-publishing budget of this edition precluded. I can only hope that the value of this book will be discovered and understood by the libraries and schools as well as individual readers who might purchase it. Compensation should be available for the amount of dedication, insight and talent this effort and others like it have required. A hardbound edition would make it much easier to trace the strands of story, influence and experience like so many melodies spinning out with complex quirks and twists potentially without end that thread through Wail.

PPS. — Wail includes as an appendix Pullman’s groundbreaking, comprehensive research of the notorious “cabaret card” laws that hampered the careers of Powell, Monk, Parker, Davis, Billie Holiday and lesser-sung entertainers in New York City for some 80 years. It turns out the “laws” were at best quasi-legal, in practice subject to wide variance of interpretation and enforcement, kind of double jeopardy, just as capricious a curse as long assumed. There’s a lesson here, beyond that pertaining directly to Bud Powell.

PPPS — JJANews has learned that Wail: The Life of Bud Powell will be available for sale as a paperback, at the author’s website (www.BudPowellBio.com), from October, 2012.

Paul is Not really the best writers.. of course no disrespect to Bud Powell..

If you mean "Peter," not "Paul," I disagree -- Peter Pullman is a very proficient and clear writer. He is not trying to be a stylist in this book, but his writing is cliche-free, and he consciously tries not to repeat himself but always to move the story forward.

thank you, i fully agree!