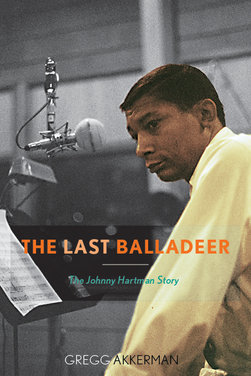

The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story By Gregg Akkerman (forward by Kevin Mahagony)  The Scarecrow Press. Inc. (2012), 367 pages, $55.00

The Scarecrow Press. Inc. (2012), 367 pages, $55.00

Gregg Akkerman’s new biography of Johnny Hartman bears the suitably elegiac title, The Last Balladeer. But after reading the author’s litany of missed opportunities, shoddy management, poorly produced (and marketed) recordings, racial roadblocks and sheer bad timing that characterized the singer’s career, a more appropriate subtitle might have been, “The Unfulfilled Promise of Johnny Hartman.” Ultimately, however, the power of one transcendent album – his 1963 collaboration with John Coltrane – bolstered by a lifetime of brilliant singing, personal and professional integrity and the respect of his peers, not only leaves the reader with admiration for the vocalist, but eager to seek out additional recordings from his sizeable (if underappreciated) discography.

During the course of his absorbing and briskly paced narrative, Akkerman chronicles the story of Hartman’s life, while correcting a number of factual inaccuracies (many generated by the singer himself) that have crept into previous accounts of the elegant crooner. Born in 1923 in Houma, Louisiana, Johnny Hartman joined his parents and five older siblings as an infant on the Great Migration to Chicago, where his close-knit, aspirational family established itself within the city’s African-American working class community. Like so many of his peers, Hartman first exposure to singing was in the Baptist church (a congregation that included another great jazz vocalist, Dinah Washington). But unlike most singers who “crossed over” from the spiritual to secular realm, Hartman eschewed the fervent, emotionalism of gospel. “I was a cool singer even when I sang in church,” Hartman once declared. “That was just me, my style of singing.” And so it would remain.

Hartman’s interest in music was reinforced during his time at DuSable High School, where, during the course of his long teaching career, legendary music director Walter H. (“Captain”) Dyett nurtured an astonishing array of African-American talent (in addition to Hartman and Dinah Washington, DuSable alums include Clifford Jordan, Johnny Griffin, Dorothy Donegan, Wilbur Ware, Nat “King” Cole, and Redd Foxx). According to one graduate of the school’s music program, students who survived Dyett’s rigorous training would have been “qualified to do a Broadway show” – that is, if New York theaters of the era had been open to black performers.

Although Hartman listed his career goal as “Business Man” in the school’s yearbook, in 1940 he enrolled in the Chicago Music College at Roosevelt University where his studies focused on correct vocal production, proper enunciation and pitch control – all of which would become hallmarks of his popular singing. In 1943, the19-year-old Hartman’s studies were suddenly sidetracked when he received greetings from Uncle Sam. But – in a story Akkerman admits is probably apocryphal – when the recent inductee was heard singing in the shower of a Virginia army base, he was immediately reassigned to the Special Services and was soon performing at local bases and at Washington D.C.’s Walter Reed Hospital.

By 1946, Hartman was back in his hometown singing at South Side nightclubs, and recording for a couple of local indie labels. Unfortunately, the timing couldn’t have been worse for a singer of Hartman’s talents and musical predilections. The Swing Era big bands that had offered a showcase for so many successful vocalists were now virtually extinct, and Hartman’s brief stints with Earl Hines’s large ensemble in 1947 and a slightly longer one with Dizzy Gillespie’s Orchestra a year later would amount to little more than an epilog to a musical style that had launched the careers of an entire generation of the county’s most successful vocalists. Meanwhile, as the decade came to an end, African-American listeners were dancing to a whole new beat – the rollicking, gospel-tinged sound of rhythm & blues that was the antithesis of Hartman’s laid-back aesthetic.

For much of the 1950s Hartman struggled to gain a foothold in popular music scene. Although he was recording regularly with a succession of independent labels, and produced a series of sides for RCA Victor, he never had the kind of breakthrough hit that could have vaulted him to national prominence. Hartman continued to work the mostly African-American club circuit, got airplay from a handful of loyal disk jockeys who admired his plush baritone and musicianship, and he even got the rare opportunity for a network TV guest spot or two. By the end of the decade, following the dissolution of a brief early marriage, Hartman had met and wed the love of his life, Theodora (Tedi) Boyd, and eased into the stable life of a husband, father of two daughters, and – or so it seemed at the time – the prospect of an extended career as just another journeyman popular singer.

Though it occupies barely a dozen pages in a densely-written, full-scale biography, the centerpiece of the book is Akkerman’s definitive exploration of the single day in 1963 that changed everything. Aptly titled, “The Mythology of a Classic,” the chapter not only painstakingly documents Hartman’s classic collaboration with John Coltrane – recorded on March 7 of that year (in a three-hour session) – but it also provides a prism through which one can view the remainder of the singer’s problematic professional life. Along the way, Akkerman gathers together all the available facts about “A-40” (the Impulse catalog number for the album titled simply, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman), provides musically-astute descriptions of its six tunes, and dispels a series of long-standing myths (no, they weren’t all single takes) – while wisely avoiding the temptation to analyze the album’s sublime alchemy. But, it’s the author’s depiction of the record’s unintended consequences that provides an ironic coda to his story of A-40.

When Hartman’s collaboration with Trane was released later that spring, the enthusiastic reviews it garnered in the music magazines (along with its respectable sales figures) prompted Impulse to feature the 40-year-old balladeer on his own LP, backed by a band of top-shelf jazz musicians. But neither it nor the four others on the label issued over the next few years were able to launch Hartman to the level his talent warranted. Of course, it didn’t help that the so-called “British Invasion” heralded by the Beatles arrival in America in February 1964 would completely decimate the jazz scene itself. While Hartman’s “tales of woe” weren’t unique – by the late 60’s, Akkerman explains, “there were hardly any nightclubs left hiring the previous generation of non-rock vocalists” – his identity as a “jazz singer” (along with the restrictive racial policies of the few up-scale supper clubs that survived), made it even more difficult for Hartman. “I was trapped in jazz,” the singer recalled of this period in a 1981 interview, “and I couldn’t get out.”

Not that the singer was given to self-pity. As Akkerman makes clear, the “optimistic” Hartman just kept plugging away: touring Europe and Japan (where his album with Coltrane made him a revered performer), creating a Nat Cole tribute act that took on the road for years, even studying acting (and getting a couple of well-reviewed roles). Periodically, he’d get the chance to record another album, one of which, his 1981 release, Once in Every Life, earned him his only Grammy nomination for Best Male Jazz Vocalist. A year later, an already-ailing Hartman cut his final tune, the title track for the sequel to the X-rated film, The Devil in Miss Jones (don’t ask), and on September 15, 1983, Johnny Hartman died of lung cancer at the age of 62.

Over the years, Hartman’s collaboration with Coltrane has earned its place as one of the classic jazz albums of all time, as well as one of the greatest vocal recordings of any genre, and it continues to attract legions of new fans year after year. In 1995, when Clint Eastwood set a crucial seduction scene in his film The Bridges of Madison County to Hartman’s 1980 recording of “I See Your Face Before Me,” it not only brought the singer to the attention of a massive new audience, but reinforced his music’s reputation as a potent aural aphrodisiac. After the film’s soundtrack – featuring four Hartman sides – became a fixture on the Billboard charts, there was a flurry of reissues of the singer’s own out-of-print albums, and a new generation of jazz vocalists including Kevin Mahogany and Kurt Elling acknowledged his influence with their own Hartman tributes.

While Akkerman makes no effort to plumb the singer’s psychological depths (or to provide Balliettian descriptions of his vocal magic), with this lucid and meticulously researched new book Hartman – whose life and career were models of self-effacing professionalism – finally has the biography he deserves.

As one would expect of a book in the scholarly but accessible Studies in Jazz series, Akkerman, an Associate Professor of Music at the University of South Carolina Upstate in Spartanburg (and himself a performer of standards from the Great American Songbook) provides a set of comprehensive appendices including a session-based discography, complete listing of all the songs Hartman recorded, and a timeline of key dates in his life and career.

* * * *

David Kastin is the author of Nica’s Dream: The Life and Legend of the Jazz Baroness.

I heard him on the Cox singers for the first time. Never heard of him before. He was an outstanding singer and reminded me of one of the greatest, Nat King Cole. Unfortunate that he didn't get the acclaim he deserved in the 60's-80's. when his style was popular.