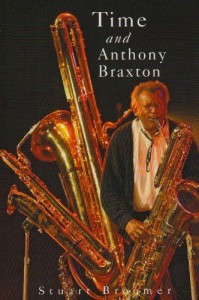

Time And Anthony Braxton

Time And Anthony Braxton

By Stuart Broomer

The Mercury Press, Toronto, 2009; 176 pages; $19.95 paperback.

Over the past two decades Stuart Broomer has become such a prolific and thought-provoking critic that it might have slipped by many of his readers that he comes to writing about contemporary music from the inside out; that is, he is an experienced pianist who began as an improvising artist – witness his impressive 1976 duo album with the Canadian saxophonist (and writer/editor/photographer) Bill Smith, Conversation Pieces, on the Onari label. But if that slice of vinyl is hard to locate today, at least his criticism has appeared in prominent places – the Toronto Globe and Mail, Musicworks, Signal to Noise, Down Beat, Cadence, Coda (which he edited for a time) among them, and he is currently a featured columnist for the online magazine Point of Departure. (Full disclosure: I write a column there as well, and wrote for Coda while he was editor, but we have never met.)

From time to time Broomer has turned his attention to the ever-challenging music of Anthony Braxton, and relevant material from his reviews, articles and liner note essays has been revised and greatly expanded to shape this book’s theme. To this end, Broomer explores various means of relating Braxton and his music to time in both its external (that is, historical/chronological) and internal (or durational, as a musical component) representation. He suggests that our individual perception of time is manipulated by music – which colors it, inhabits it, stretches or shrinks or even suspends it, gives it an identity and significance – and explains how Braxton’s distinctive, multifaceted music may focus our attention on and increase our awareness of the cultural, scientific, philosophical and spiritual affinities and relationships that serve to humanize time.

To do so, Broomer describes several areas of Braxton’s musical cosmology – his notated solo piano scores and improvised/systematized solo alto saxophone performances; the collaged interplay of his quartets; his approach to the standard repertoire; his sense of orchestral synchronicity; and his recent compositional blueprints, the Ghost Trance Music and Diamond Curtain Wall Music. He offers a condensed but clear account of Braxton’s roots in Chicago and the inspiration he drew from the city’s abundant diversity of sounds. He even weighs in on Braxton’s attraction to low frequencies, cites his symbolic connection to marches and touches upon his devotion to cardigans. But most interesting is the way in which Broomer not only places Braxton’s music in an expansive musical perspective that includes classical and world music, but connects him to a larger body of cultural modernists and philosophical and artistic visionaries. Not to say this is an original concept; Graham Lock (Forces in Motion, Blutopia), Mike Heffley (The Music of Anthony Braxton) and others have created similar, equally effective constructs. But the breadth and wit of Broomer’s frequent references to poetry and fiction – from Borges to Vonnegut, Pound to Pynchon – as well as his scientific analogies and wide-ranging musical associations, are as surprising and stimulating as they are persuasive.

In fact, the only disappointing aspect of the book is that the implications Broomer draws from his study of Braxton’s music are so potentially rich, it’s a shame that he is so concise. Like a fine pianist, Broomer is able to articulate an idea with a deft turn-of-phrase and develop it through uncharted territory with convincing aplomb. Often, however, he sets the groundwork for provocative topics that would blossom with a more detailed examination, and provides only short examples or a curtailed explanation – for example, the distinction between free jazz and free improvisation, especially in the latter’s European guise, or his daring speculation on velocity throughout the course of jazz, which leaves so many enticing possibilities unexplored. Many examples from Braxton’s immense catalogue of works are mentioned but not always described fully enough to make sense to the Braxton novice. This may, in part, be the result of adapting his material from the original space-limited sources, or the publisher’s request for a book of reasonable length. In any case, the amount of helpful, perceptive information on Braxton herein, and the engaging, user-friendly manner of presenting it, make this book, if not necessarily the best place to begin a journey into Braxton’s unique and rewarding world, definitely a welcome and worthy addition to the existing literature.