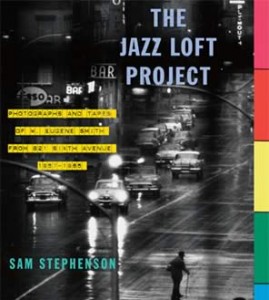

The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957 – 1965

The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957 – 1965

By Sam Stephenson

Alfred A. Knopf, and Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University, 2009;

288 pp.; $40 hardcover

When W. Eugene Smith (1918-1978) moved into his storied loft in New York, he was already a superstar of the photographic world somewhat trapped by his own legend, in full retreat from the world at large. He had been World War II’s photographer-equivalent of Ernie Pyle, and his postwar work, mostly for Life, had redefined photojournalism, lifting it from narrative to interpretive as he developed (some would say perfected) the photo essay. At the time, Smith was also still heavily invested in his most ambitious and frustrating undertaking, the multiyear Pittsburgh Project, which Sam Stephenson edited into its most extensive and magnificent form to date in an earlier volume, Dream Street (W.W. Norton), about a decade ago.

Smith was a tortured soul to say the least, an obsessive perfectionist, willing to go without sleep for days and nights in the darkroom — aided by a diet of scotch and speed, his record player turned way up — to make the most incredibly beautiful prints mere mortals can. He also taped his own recordings of what went on in the loft — jam sessions featuring a who’s who of the day’s vibrant New York jazz scene, and most notably Thelonious Monk’s big band rehearsals for the first Town Hall concert.

There are no CDs included with Stephenson’s The Jazz Loft Project, but there are transcriptions from some of his many tapes of radio and television broadcasts, Smith’s raw telemetry of history unfolding as he lived through it. (There is more, including audio, to be found on the related web site jazzloftproject.org, and in a companion touring exhibition, currently at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts through May 22.)

Smith’s only subjects outside of 821 Sixth Avenue were passersby he could see from the remove of his fourth-floor window, though his work from that vantage point, some of which is included in this volume, isn’t as consistently poetic as what André Kertész did from a higher perch above Washington Square Park. Other than that, Smith’s subjects comprised the changing cast of fellow residents, including musician Hall Overton and painter David X. Young.

[pullquote]Smith left a magnificent mess; Stephenson has not only organized it but made sense of it as well.[/pullquote]

Then there were the visitors, a roster of the distinguished and the obscure. Stephenson has documented 589, including Mose Allison, Diane Arbus, Albert Ayler, Art Blakey, Carla Bley, Jaki Byard, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Salvador Dalí and Miles Davis, and that’s skimming just from A to D.

At any hour of the day, but more frequently of the night, there were jam sessions and elevated conversations, fueled by all sorts of substances, some legal, a certifiably hip scene. Smith prolifically photographed the musical goings-on at 821, but his images of Monk deserve special mention. Monk is seen totally in the moment, completely caught up in music not yet perfected, among friends and colleagues, not mugging for an audience. He is depicted with the force and strength of a Rodin sculpture, but then Smith had a way of doing that to subjects he liked.

We can never know if those two eccentric geniuses felt any connection, conscious or not, as fellow manic-depressives, but these are the most intimate — and, to my eye, the best — photographs of Monk in existence. Like all of Smith’s photographs from 821, they possess an almost abrasively grainy yet also velvety quality, born of shooting patiently and unobtrusively in the available darkness of the loft, within the limits of the technology of the day. By themselves, the Monk pictures make the book worthwhile, but it has much more to commend it.

There are innumerable fascinating tidbits in the texts, such as Smith advising Ornette Coleman on a Guggenheim fellowship application (which was successful), Bill Evans crashing for several consecutive days on a sofa, and a technical explanation of how Smith got that subtly diffused effect on selected prints: by letting the booming bass speakers in his darkroom sound system slightly shake the enlarger during the prints’ exposure.

The only correct answer to the question whether this is a book of texts, profusely illustrated, or a volume of engaging photographs with supporting texts, would be “yes.” Smith left a magnificent mess, and Stephenson, in his second decade of research on the man, maintains the same simultaneous eye both for detail and the bigger picture. He has made serious inroads not only into organizing some of the Smith collection’s 22 tons, but making sense of it as well. Smith was famously — or infamously — unsatisfied with how most editors handled his work, and this caused him to quit Life magazine several times. So he likely would not be pleased with what Stephenson has done, but I hope Stephenson is. He should be.

Stephenson certainly seemed happy at the book’s debut to-do in Durham last December, which featured live music by the Ron Free trio. Back in the day, drummer Free, who is depicted in the book, was one of the regulars at the loft (and one of the more energetic and creative, according to another 821 rhythm section participant-youngster, Steve Swallow). It was a magazine piece by Stephenson, written in the course of researching Smith’s work, that brought Free out of obscurity a few years ago. Thus this was a totally righteous gig, with the variety of nicely rendered standards being exceeded only by a soaring free improvisation in the later set, well worthy of 821’s flights of fancy, though those of us there with cameras were all too aware of being in the long, deep shadow of Smith himself.