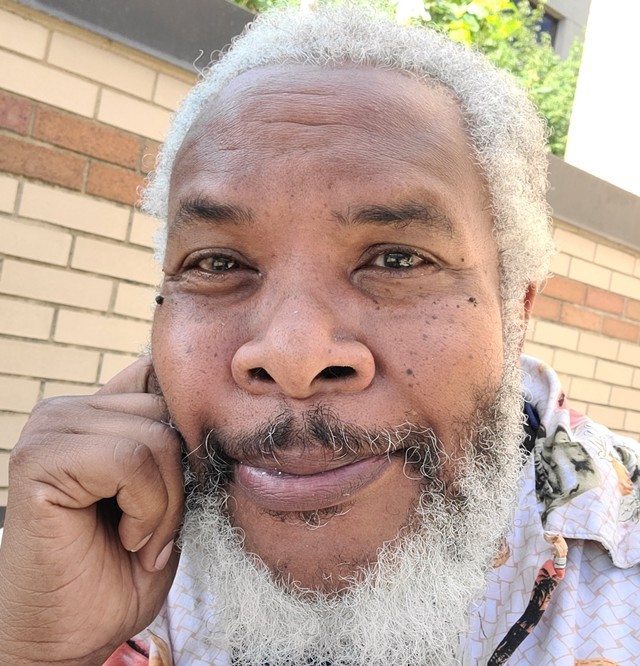

Reuben Jackson, an acclaimed Washington-based jazz historian, radio host, poet, teacher, music critic, died on February 16, 2024. The previous week he suffered a stroke. He was 67.

[Ed.’s note: A longtime member of the Jazz Journalists Association, Reuben Jackson published poems at JazzHouse.org as well as a celebration of Duke Ellington, pianist and is heard recently speaking about jazz archives on The Buzz, the JJA podcast.]

Although he was born in Augusta, Georgia, on October 1, 1956, Jackson mostly grew up in Washington, D.C.’s Petworth neighborhood. His father, Pierce Jackson, was an electrical engineer while his mother, Mary Alice, was a teacher and language arts specialist. He had an older brother named Al.

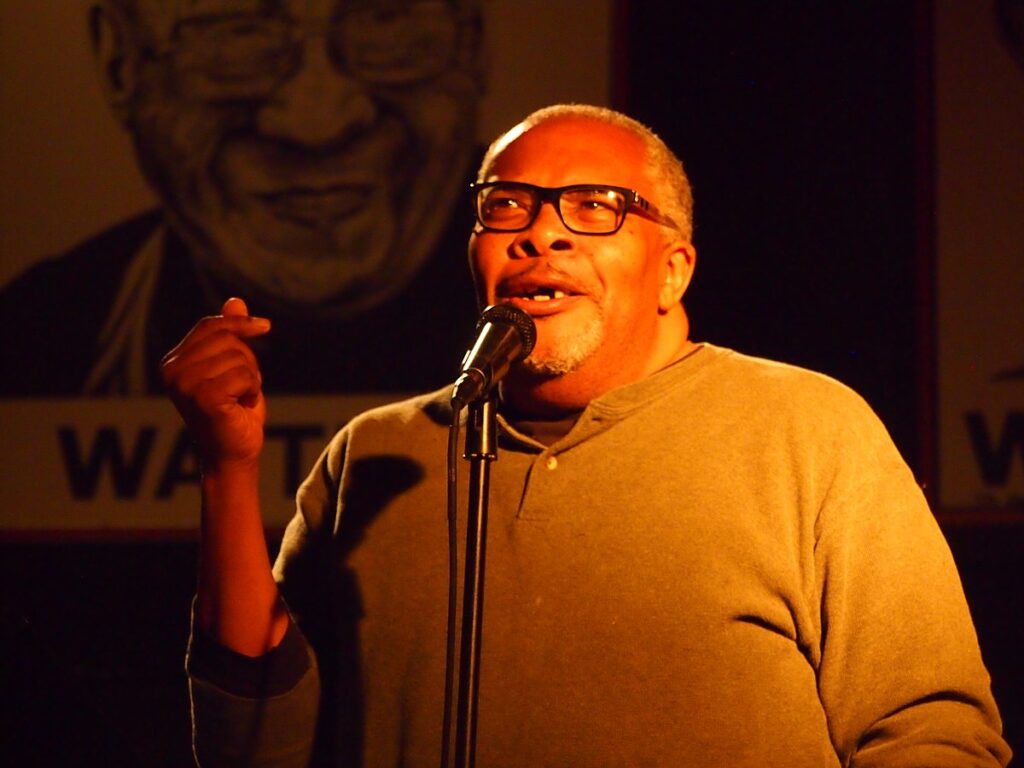

Jackson’s presence in the D.C.’s cultural ecosystem was as influential as it was omniscient. He was often heard on WPFW-FM (89.3), a Pacifica radio station, co-hosting the popular jazz show, “The Sound of Surprise,” on which his catholic taste of music would entrance listeners with a program that included music from artists ranging from Bill Frisell and Carla Bley to Duke Ellington and Santana. As a music critic, Jackson also contributed to JazzTimes, The Washington Post, and National Public Radio’s All Things Considered.

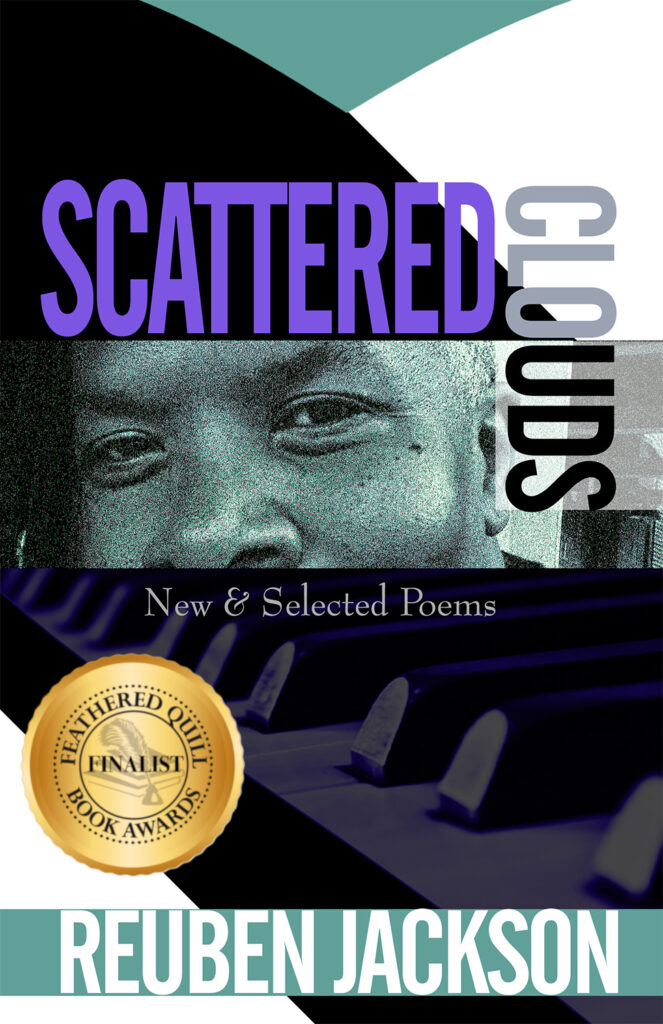

His encyclopedic knowledge of music was matched by his brilliance as a poet and teacher. For 11 years, he taught poetry at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Some of his early works were first anthologized in 1991 with his first book fingering the keys (Gut Punch Press), which focused mostly on his love for music; the following year, the book won the Columbia Book Award. Jackson released another book of poems, Scattered Clouds: New & Selected Poems (Alan Squire Publishing), in 2019, which contained some poems from his first book as well more newer ones that centered on love, longing, and loss.

Jackson’s poem, “for duke ellington” was most recently included in Kwame Alexander’s This Is The Honey: An Anthology of Contemporary Black Poets (Little, Brown and Company), which came out in January 2024.

Speaking of Ellington, Jackson worked at the Smithsonian American History Museum’s Archives Center on its Duke Ellington Collection as an archivist and curator between 1989 and 2009. It was the summers of 1989 and 1990 that I first discovered another important descriptor for Jackson – mentor.

When I first arrived in Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1989 as a Smithsonian intern on the Duke Ellington Collection, Jackson quickly became one of the first mentors. I was still an undergraduate student at Mississippi State University, trying to make my way into adulthood. I was brimming with passion for music but barely had a compass to help me navigate it into the professional world.

At the time, I hardly knew of Ellington’s eminence beyond him being reverent footnote. Jackson recognized that but he never made me feel inferior about my ignorance about Ellington or any other jazz icon. He would be just as conversant and enthusiastic about some of my favorite artists – Prince, Jimi Hendrix, Chaka Khan, Sheila E., Parliament-Funkadelic and Earth, Wind & Fire – as he was about Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Ben Webster, and Johnny Hodges.

In fact, Jackson encouraged me to continue indulging in my music taste and my ravenous new and used LP crate digging to enable me in developing my own perspective about the expansive world of jazz and how it relates to R&B, blues, Latin music, disco, hip hop and deep house music.

About two or three weeks into my internship, I expressed my burgeoning love for Miles Davis. The next day, without prompting, Jackson gave me a copy of the four-LP boxed set, The Columbia Years 1955 – 1985. Befriending Jackson was one of the reasons I applied for the same internship the following year with plans to make D.C. my home. In Mississippi, I didn’t have any Black role models, who exhibited a deep love for music, collected records, yet still made it work for them in the professional world without them being a musician.

During my second summer in D.C., I soon learned that Jackson was a regular contributor to the city’s acclaimed alternative weekly newspaper, Washington City Paper.

In early June 1990, the City Paper published Jackson’s poignant cover story, “A Branch Apart,” which gave harrowing details about his time working with at-risk kids as a librarian inside the children’s room of the D.C. Public Library’s Anacostia Branch. Such brave, honest, and eloquent features as well as his incisive album reviews for the City Paper inspired me to want to write for them. I would give Jackson copies of my music journalism from Mississippi State University’s newspaper, The Reflector and magazine, The Prism, for his review. My writing was never as personal, polished, and edifying as his; nevertheless Jackson saw a diamond in the rough. He knew that I had a skill, worthy of improving and investing. And for an impressionable, shy, Black queer kid from Mississippi, his encouragement was more than enough for me to move forward.

Jackson also showed that mentorship could evolve into true friendship. Whenever I saw him at the Smithsonian, in a record store, at a concert, or just on the street, he greeted him with avuncular hug that also help me as a queer person cut through the narrow-minded, hateful narrative that the Black community was more homophobic than its white counterpart. People like Jackson – as well as other Black mentors in the city, such as Willard Jenkins, Suzan Jenkins, Katea Stitt, Bobby Hill and Bob Daughtry – helped make me feel increasingly comfortable in my skin.

After Jackson retired from the Smithsonian, he moved to Vermont, the state where he earned his bachelor’s degree from Goddard College. As a college student in the mid-1970s, Jackson got his first gig as a radio host and producer at the college’s station, WGDR.

Jackson reprised that passion for jazz radio in Vermont between 2013 and 2018, by hosting “Friday Night Jazz” on Vermont Public Radio. He also mentored aspiring writing teens at Burlington High School’s Young Writers Project.

When Jackson returned to Washington, D.C. in 2018, he resumed his archival expertise by working at the University of the District of Columbia’s Felix E. Grant Jazz Archives. Jackson was also a founding member of the New Music – Theatre workshop.

Through his published poems, journalism, radio programs, teachings, and mentoring, Jackson’s multi-faceted legacy will continue to inform Washington, D.C.’s cultural community for decades to come. Jackson is survived by his partner Jenae Michelle, his extended family in Georgia and, as reported in Seven Days, the Vermont independent publication, “wonderful group of chosen family.”

for cassandra wilson

an old friend

calls to tell me

“she’s abandoned jazz”

– his voice a moaning

delta breeze.

when he’s done,

i call miss cleo;

who, fake caribbean patois

aside,

assures me there’s never been

no desertion in the music’s

fifth house,

or something like that.

i swear i hear the

infidel in question’s

version of james taylor’s

“only a dream in rio”

in the background,

along with tarot cards

shuffling like a great

tap dancer.

my dear myopic friend,

evolution has always been

a band book with countless chapters.

how could charlie parker

quote stravinsky,

if the music did not

check out everything?

reuben jackson

copyright © 5/2002