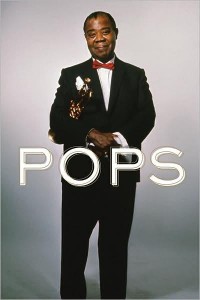

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong

By Terry Teachout

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston/New York, 2009;

496 pp.; $30 hardcover

If we subscribe to the theory that there should be at least one book on Armstrong every decade, then this thoroughly researched tome is the one for the 2010’s. And it should be a bestseller as well. Pops is as carefully planned and executed a life of Louis Armstrong as any I have read. The uninitiated might get the impression that they were living with him, selling the coal to the prostitutes, running in the streets of New Orleans shooting off that pistol, ending up in that waifs’ home, having been saved from a fate that might have ended “jazz” before it began.

However, it took some chapters to get to the new stuff. The early going can feel more like a book report rather a new book. Teachout repeats information wholesale from others, notably Gary Giddins’s Satchmo, long my favorite Louis book and video, which I continue to show in its entirety to all my classes. But what Teachout does accomplish is to put it all into proper contexts. There are chapters on Louis’s addictions to marijuana and the laxative Swiss Kriss, his relationships with Earl “Fatha” Hines, European encounters and his inexplicably nearsighted devotion to his manager Joe Glaser, all from revealing personal perspectives making for engaging reading.

Missing is a full account of what Louis did that created our music, and how it all intertwined with his personality. Teachout hints at this, saying that Louis was strong and wouldn’t let others tell him what to play or how to play it. He does tell us how after Glaser took over, Louis let this former Capone mobster dictate how to make millions from his minions. But Armstrong’s dramatic sense is nowhere to be found: the stop chorus, the improvised solo breaking away from group improvisation that was standard in New Orleans music. Of singular importance was the introduction of the 4/4 swing tempo that presaged the big band era. Teachout notes that Louis’s big band was roundly criticized, so he did not fully participate in the swing era’s popularity. He finally gave it up and formed the All Stars, the small groups that would be with him for the rest of his life.

Louis was jazz’s first entertainer, and Teachout reports that Louis insisted his sets never vary, not in terms of song order or even the banter. “I play what I know,” Louis is quoted as saying. As elaborated in Pops, his hiring of and devotion to the rotund singer Velma Middleton was embarrassing. A personal aside: Having booked the All Stars into Brooklyn College in 1958, I made the mistake of asking Louis not to bring her to the school as I was trying to increase the jazz audience, and I thought Middleton not to be jazz. (I still feel that way.) [pullquote]Responding to doubts about the veracity of this anecdote raised by Dan Morgenstern in comments below and Michael Cogswell in an email message, Arnold Jay Smith writes:

“I humbly beg the pardon of those whom i have offended in my seeing Louis smoking at Brooklyn College in 1958. That was a long time ago. I have no other proof as all involved are long gone. Again, I am sorry for the offense. As for Ms. Middleton, Louis probably looked at me as some punk kid who didn’t know any better.”

[/pullquote]Louis’s reaction was silence. At the same concert, his pot habit nearly cost me my college career — I might have dodged the jail-time bullet — as he and the band were imbibing during the show.

It’s in the research that Pops proves its mettle. You will never need another Armstrong reference book if you consult his lengthy appendices and index, running to dozens of pages of discography, bibliography, references and cross-references. Teachout has culled from all the correct sources: George Avakian, Phoebe Jacobs, Dan Morgenstern, Gunther Schuller, George Wein and more. His stories of Louis’s encounters and lifestyle were all made available to him as to no other writer.

I can only imagine the ecstasy when Teachout discovered the treasure trove found at the Armstrong Queens College Archive. When I was preparing for my first Jazz Insights class at the New School in 1979, Lucille Armstrong and Dick Hyman were to be my guests, and Lucille invited me out to the house, now a historic landmark. We shared lunch, squatting on the floor of the famous living room, an island in the midst of recordings of every stripe by and about Louis. Teachout refers repeatedly to Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography (Decca), which was narrated by Armstrong. Lucille endorsed her last copy of the LP box to me, and it now resides at the Queens archives.

This is a warts-and-all book. If you want to believe in Louis’s purity of heart, don’t read it. Otherwise, Pops is a need-to-have guide to the life and art of jazz’s greatest icon.

It must have been Arnold, not Louis, who was indulging that night in 1958, causing him to hallucinate, or to confuse a Camel with a joint. Louis Armstrong didn't smoke pot in public, never while performing, and most certainly not on stage, nor would any of his sidemen have been permitted to do so. It is a disgrace to see such foolish and slanderous horseshit published in a source representing professional journalists. Smith should have been asked to furnish proof of this ridiculous claim. We are further asked to believe that a college student would have had the nerve to request that an artist of Armstrong's stature adjust his group's personnel--aside from being idiotic, it would have been a breach of contract. If indeed Arnold Smith had asked Louis not to feature Velma Middleton, his face or groin would still bear the marks of the appropriate response, assuredly not silence!. It is hard to imagine this entire ridiculous and offensive scenario--unless you happen to be Arnold Jay Smith. I strongly suggest prompt removal, with an apology.

I was stunned to read Mr. Smith’s contention that he witnessed Louis and his band smoking marijuana during a performance at Brooklyn College in 1958. The concept of Louis “imbibing during the show” is as ridiculous as it is offensive. Yes, Louis was a regular pot smoker, but he was always a consummate professional. Of the thousands of resources of the Louis Armstrong House Museum (e.g., Louis’s candid home-recorded tapes, oral histories with band members, biographies, newspaper and periodical articles, my own conversations with those who knew Louis well) not one supports such a claim. I know Mr. Smith and have had the privilege to attend and to address his Jazz Insights class. Perhaps he can elucidate what he remembers.

I just read Arnold J. Smith's review of Terry Teachout's splendid book, "Pops: "A Life of Louis Armstrong." As a friend of Arnold's, as well as a much closer friend - from 1940 until forever - of Louis Armstrong, I take umbrage at the statement, "If you want to belileve in Louis's purity of heart, don't read it."

If any person, among the thousands I met in a the jazz world in a span of more than 75 years, had a totally pure heart, it was Louis Armstrong. He was the epitome of kindness, thoughtfulness and grace, with a boundlessly pure love of his fellow man. He sprang from the roughest of origions and could be tough when necessary, but the gentle goodness of his very being remained paramount at all times.

As for his ever smoking pot on the job, or permitting it by his musicians, this is a charge that is completely unbelievable. I spent countless hours with him socially as well as professionally, and got to know him more intimately than any other artist with whom I worked. Armstrong enjoyed his marijuana - suppposedly every day of his adult lilfe - but he was no fool; he had been "busted" early on, and knew better than to make a public spectacle of his enjoyment of the weed. Nothing would have been more out of character.

George Avakian