Sad to hear that Phil Schaap has passed.

Our paths intersected during my 1985-2008 stint at WKCR, Columbia University’s radio station. I didn’t know him too well — though we did have personal conversations at several points along the way.

I think he was a great man — an extraordinary communicator, master educator, modern griot, repository and profound interpreter and analyst of culture, public intellectual of the highest order. I consider Schaap, in his encyclopedic, completist scope, as a parallel figure to Diderot or Macauley or DuBois or Alan Lomax or Appiah — I’m quite serious about this. He set a high bar to live up to for anyone who programmed at WKCR.

Schaap had a photographic memory for birthdays, phone numbers, statistics, recording dates, which he could access like a computer. It seemed to me that these were parlor tricks, kind of a distancing mechanism, a conversation starter. What made him extraordinary to me — and to thousands of his fans and students — was his ability to process and synthesize the immense amount of information that he accumulated and lived.

His father Walter Schaap was a jazz scholar and discographer who had close relationships with a number of eminent Black jazz musicians during the 1940s and ’50s. So Phil grew up in jazz, knew people like Roy Eldridge and Papa Jo Jones and Earle Warren from childhood — they were, in his psyche, literal family.

As he would sometimes reveal in those endless radio lectures-soliloquies (“Why doesn’t he play some music?”), he had a profound understanding of jazz history on the cellular level and could contextualize it on the meta level, in complete and well-turned sentences and paragraphs. During Schaap’s years at Jazz at Lincoln Center, for example, he could convey to Ali Jackson, say, how Papa Jo Jones or Sonny Greer executed a particular beat, down to the way they held the drumstick.

Unfortunately, Schaap didn’t publish. I hope that he left behind an manuscript (or two or three). I seem recall that he was essaying a book and a collection of interviews — but I had the impression that, paradoxically, Schaap liked to hold information close to the vest. Hopefully funding can be found to have his extraordinary archive of interviews – which exist in various media, including reel-to-reel tape – transcribed, intelligently edited, and made readily accessible.

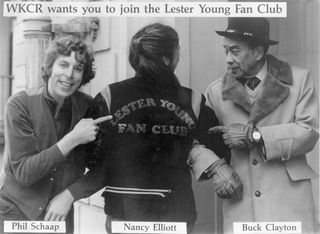

posted 2011 at WFMU blog by Nat Roe

Schaap was best known for his radio raconteur persona, but he also walked the walk. He had a very powerful personality — he understood the politics of culture and how to tailor WKCR’s programming to his imperatives. Via his “Bird Flight” and “Traditions in Swing” broadcasts (not to mention day-long birthday broadcasts for Max Roach, Clifford Brown, Ornette Coleman, Bix Beiderbecke, Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lester Young, Bird, Thelonious Monk and Roy Eldridge) which began in the early ’70s and lasted until his death, he made New York City’s jazz audience – “civilians” and practitioners alike – pay attention to Charlie Parker and bebop.

The sessions he produced at the West End down the block from the Columbia campus during the ’70s and ’80s allowed young musicians who knew what they were looking for to intersect with the old masters — and gave the elders work and helped them sustain artistic confidence. He was a diligent sound restorationist and a good engineer — as one example, his work codifying Bird’s Verve and Savoy recordings and various airchecks/location broadcasts with best possible sound, correct pitch, and discographical provenance.

He gave.

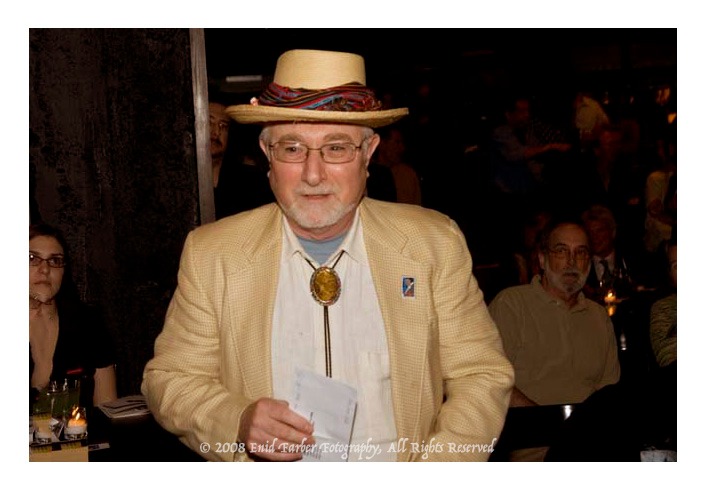

photo by Grayson Dantzic

I don’t want to give the impression that we were friends, or that I had privileged knowledge – these are observations distilled over my 23 years at WKCR, and as a sometime listener for much longer than that.

Ted Panken is a recipient of the JJA’s Lifetime Achievement in Jazz Journalism Award, and the JJA’s 2021 Award for Excellence in Writing. Phil Schaap was twice honored by the JJA for Excellence in Broadcasting.