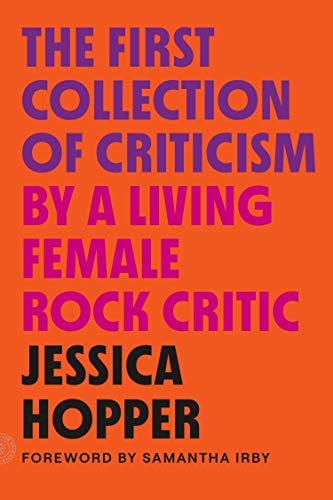

Harmony Holiday writes a stellar Substack (blog/newsletter) entitled Black Music and Black Muses; journalist and essayist Jessica Hopper has revised and expanded her 2015 anthology, The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic.

To encourage the exploration of underrepresented voices in jazz journalism and criticism, Diverse Voices on Jazz highlights the contributions, efforts and publications of women, among others, in the form of recent reviews, feature articles, op-ed, historical and analytical non-fiction. This column is meant to offer a resource, to acquire research material for academic and non-fiction writing and to highlight the exemplary work of writers who deserve to be read, photographers and videographers whose works should bee seen, broadcasters who should be heard.

Though this column mainly focuses on jazz writings, Hopper deserves an honorable mention for opening the world to collection from a woman that has stretched the limitations of masculine-centered music criticism.

But to start with Black Music and Black Muses:

it’s Holiday’s personal compilation of essays, historical analysis and archival work, organized towards an eventual memoir, and also having grown into something like her own version of the American songbook.

One of the most poignant pieces from Holiday’s newsletter is a rumination on the intimate and platonic friendship between two iconic figures: trumpeter Miles Davis and vocalist Betty Carter. The writer opens with a brief sentence sharing that Carter and Davis met in Detroit and quickly moves into details of a friendship solidifying when the two moved to the same New York City hotel complex, Carter alone and Davis with his family.

Holiday ties in that Carter was as close to Davis as his friend Gil Evans, revealing that both Evans and Carter were both born under the sign of Taurus, whose personality attributes include loyalty and stability.

Such small details makes Holiday’s writing different: she adds little known humanistic connections that allow her deep research skills to subtly glisten. She writes about how Carter took care of Davis’ family after he disappeared from New York without a trace, but sending word from a secret distance to take on this task. Carter does what she’s asked without judgement, supporting both Davis and his family through the transition of divorce.

In the midst of the story, Holiday seamlessly drops in personal information about Davis and Carter meeting her father Jimmy Holiday, a famed songwriter, and briefly acknowledges her spiritual and “energy” bond with Black music icons through blood and a larger music community-based lineage. She expresses desires to learn more through stories and by diving even more deeply into the wealth of information her elders can provide.

Returning to the main thread, Holiday moves her piece forward reporting that Davis returned the favor by hiring Carter to perform alongside him, and connecting her to his agent. Davis also connects Carter to Ray Charles, igniting their singular collaborative album.

Holiday glides to the conclusion of her intelligent essay by focusing on the meaning of friendship and Carter’s treatment of Davis with class and compassion. She ends her essay, Blind Songs, Unsung Music with beautiful, touching words: “When you find romance that requires no rhetoric or tally, you will always find music near it, in this case, two of the best musicians who ever lived, deep in healing platonic love, and Betty promising finally, I probably know why Miles did everything he did, and I’m not telling you.” Read more of Harmony Holiday’s writing by subscribing to her newsletter at harmonyholiday.substack.com

Jessica Hopper is an accomplished music writer and editor, being the first music editor of the tween online publication Rookie, senior editor of Pitchfork, editor-in-chief of the quarterly publication The Pitchfork Review and editorial director of MTV News. The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic: Revised and Expanded Edition, released July 6 2021, updates her second book, The Girls’ Guide to Rocking: How to Start a Band, Book Gigs, and Get Rolling to Rock Stardom of 2009 having been her first. This second edition of The First Collection comes three years after Hopper’s Night Moves, a memoir of grungy Chicago in the ‘ Aughts, published in 2018. The First Collection’s “revised and expanded” aspect involves inclusion of some of her newer work and an introduction by comedian and writer Samantha Irby.

The book has a unique introduction. Instead of writing something that focuses on the process, emotional investment and pain it took to compile The First Collection, Hopper shares an essay entitled “I Have a Strange Relationship with Music,” from the spring 2002 issue of Hit It or Quit It, a zine she founded that grew into a widely-read magazine (ended in 2005). In it she unfold the intricacies of Van Morrison’s album T.B. Sheets.

photo by Joe Mabel

And from there on it’s obvious that her personal appreciation for music and expression of her sensitive, complex, ebbing-and-flowing emotional states are the cruces of her music writing.

Hopper curates her book into sections drawn from her distinct back-catalog. Chicago-based, she begins with a handful of her pieces on Chicago-based musicians, including one on the musical life of Chance the Rapper. Subsequent sections have headings like “Real/Fake,” “Death/Redemption” and “Nostalgia.” She has not grouped articles in chronological order and there is no point in trying to find rhyme or reason to her selections if you don’t truly know her. Surrender and go along for the ride to learn about who Hopper is as a writer and human being.

Her storytelling is bright and poignant; she creates vivid imagery. Her voice is lyrical, brilliantly toned and softly literary. She stands out with seemingly effortless ability to heighten her articles’ quality by being thoughtful and artistically articulate. She conveys scenes by giving just enough information to embed a crisp visual in the minds of her readers. Here she re-creates an intimate backstage experience of musician Janelle Monáe who was vulnerable to inclement weather as she prepared for a show in Atlanta:

Janelle Monáe is utterly composed as she tromps to set through mud puddles in lengths of banana-hued silk organza and a pair of rain boots from Lowe’s. Handlers and helpers hold her hem high, their umbrellas lofted to protect the Mongolian lamb fluff on the David Ferreira overcoat dress and Monáe’s flawlessly made-up face. Amid the downpour soaking the set on the historic Pullman Yard, a former munitions factory on Atlanta’s east side, Monáe approaches the camera poised, focused. She kicks off the boots and climbs atop a small tower of crates; she summits and smiles She knows her angles.

Janelle Monáe carries herself like a person living by stringent code. She clearly holds professionalism as a virtue. Historically, this has played as Monáe being in tight control of her image Her early career was built on a persona, with the singer identifying herself as the android Cindi Mayweather, here from 2719 on a mission. The conceit contextualized her as androgyne, but in other ways was distancing and thwarted reading Monáe’s robot-love material as biographical.”

Hopper’s writing is valuable and most certainly should be preserved, her talent so bright and her gift is so obvious that it’s hard to imagine an editor who wouldn’t want to publish such work. Her books may not make a million dollars (although they should), but she merits publication because she is doing what she is born to do and executes her work so well that she should be introduced and if necessary reintroduced to readers until she is recognized in the upper echelon of journalists and essayists, amid the likes of Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion.

Jordannah Elizabeth is a Baltimore-based writer and lecturer.