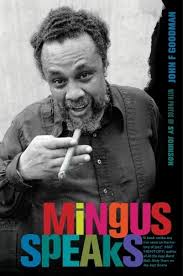

Mingus Speaks by John Goodman, photographs by Sy Johnson

Mingus Speaks by John Goodman, photographs by Sy Johnson

University of California Press, 2013; 350 pps; $34.95 hardcover, $19.22 Kindle edition

Unlike a standard biography in which the author relies on previously published articles and books about an artist, Goodman used a tape recorder. Forty years ago, while sitting in jazz clubs, bars, restaurants and even Mingus’ home, he asked the artist a series of questions about his personal life, musical training, views on black music, the true definition of “jazz” and much more. The interviews took place between 1972 and 1974, when Mingus had just made a musical comeback after being away from performing for about six years because of personal difficulties and a long struggle with depression. Up until then Mingus had been stereotyped as “an angry black man”; his own words portray his genius, his complexities and troubles. The tapes required little editing .

The year 1971 was a fruitful one for Mingus: he was beginning to perform again in public both in the United States and Europe, had just recorded Let My Children Hear Music and was asked to give a concert in New York at Lincoln Center, which Goodman attended in order to write a review for Playboy magazine, his employer at the time. After the concert the author met with Mingus, who agreed to do interviews for a Playboy feature story. Mingus consented to the interviews because he wanted to publish another book following his controversial autobiography Beneath the Underdog, needed the money and also looked forward to discussing sex, as Playboy would be the publisher. Later, the 20-plus hours of taped interviews became material for a book. The results are truly informative and unique and I highly recommend reading Mingus Speaks.

Its 13 chapters are arranged in a question-and-answer format. The tapes have been transcribed to authenticate Mingus’ sometimes hipster and inner-city dialect in depiction of artists he disliked, fights he had with cab drivers whom he found discourteous, and his analysis of the playing styles of noted artists including Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Miles Davis and the Beatles. He explains why he is critical of avant-garde music of the sixties, stating that it lacks discipline and structure; talks about the importance of receiving a classical training in music; laments the meager earnings of most jazz musicians while he credits the work he did for a while in a New York post office, and details the difficulties he encountered while recording Let My Children Hear Music at Columbia Records under the production of Teo Macero. Listening to a selection from the tapes and Goodman’s podcast interview (on the UC Press website here, where you can also read Chapter 1 of the book) enables one to appreciate the depth and richness of Mingus’ musical knowledge.

Each chapter’s q-and-a is followed by commentaries by one or more of ten Mingus friends and associates, including George Wein, Dan Morgenstern, Paul Jeffrey, Bobby Jones, Sy Johnson (who also provided photographs), Sue Mingus and the late owner of the Village Vanguard, Max Gordon. The author also adds an occasional commentary. All attest to the fact that Mingus was violent, cruel and unstable while at the same time loving, caring and generous and above all a musical genius who could not separate his life from his music. Speaking for himself, Mingus reveals his depth of knowledge about music and other artists and their compositions. His comments about avant-garde music, club managers and owners, critics, the need for black people to embrace a form of music that is their own — the blues, which he regarded as better reflecting the black experience than rock ‘n’ roll and rhythm and blues—in order to realize the importance of jazz. He felt rock was destroying jazz as a genre, and was especially critical of the use of electronic instruments in jazz ensembles: “I’ve heard nothing better than a Steinway yet, all over the world. I’ve heard nothing better than a violin.”

Jazz, Mingus thought, should not only be appreciated by upper-class African-Americans because they could afford to go to clubs to listen to Billy Taylor, Max Roach, and the like. The blues, he felt, should appeal to all black people. Particularly before and just after World War II, jazz musicians traveled with one another to gigs and learned from each other (he talked about traveling with Lionel Hampton, whose band included his Cuban friend Fats Navarro), a practice that was ending. He explained why he’d started his own record company with Max Roach, and his ambivalence about George Wein, who considered him a talent akin to Duke Ellington but without Ellington’s disciplined ability to sustain a big band.

Chapter 8, one of the most important in the book, is titled “The Critics.” Mingus was angry at Barry Ulanov, who called him an avant-gardist, and John Wilson of the New York Times, who evidently had attended one of his concerts and written a bad review, prompting Mingus to state that white critics did not understand jazz and needed to take the time to listen. In the commentary, Teo Macero declares that critics destroyed the livelihood of jazz artists because of their negative reviews. Goodman interrupts to state that he no longer writes jazz criticism because he did not want to destroy artists’ careers.

The remaining chapters deal with Mingus’ personal and financial difficulties, including an eviction from a New York residence for many reason; his relations with women in general and, specifically Sue Mingus, who cared deeply for him and understood him. His discussions of civil unrest, including the reasons for the Watts riots of 1965, are demonstrative of the times in which Mingus lived.

Mingus was ahead of that time, in that he wanted jazz to be recognized as an original art form and wished to establish a performing arts school for young black children similar to the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, DC, where inner-city children among children of all backgrounds could receive training in the arts leading them to become first class musicians, singers, dancers and even symphony orchestra conductors. Finally, author Goodman draws distinctions between the mythical Mingus and the real Mingus, who faced obstacles such as societal racism and suspicion of young black men. Mingus was a great composer, conductor and bass player, a key participant in a golden era of jazz. For this reason, I recommend reading “Mingus Speaks” and then listening to some of his music.

I love you Charlie , your music was from Heaven and I am sure you are there playing for all the good guys. Rest in Peace dear man.