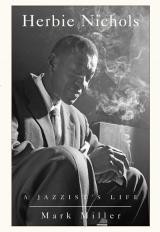

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life

By Mark Miller

Mercury Press, Toronto, 2009; 224 pp.; $19.95 paperback

The jazz world is filled with musicians who have not received the recognition they deserve. But after reading Herbie Nichols: A Jazzist’s Life by veteran journalist Mark Miller, the obscurity surrounding this pianist seems particularly tragic.

Nichols had his heart set on being a classical pianist, but because a classical career was impossible for a young African-American in the 1930s, he switched to jazz. “My earliest ambitions were to become a Prokofiev,” Miller quotes him as saying. “When I learned that I would be unable to obtain formal conservatory training I decided to become an Ellington and to enter the fascinating field of jazz.”

In the author’s notes and acknowledgements, Miller quotes one of Nichols’ admirers, pianist Frank Kimbrough: “I can’t imagine anyone coming up with enough information for a book [on Nichols].” Miller is to be commended for completing that task. However, one wonders how many jazz followers know enough about Nichols to be interested in learning more. Nichols clearly had the talent to be successful, but he had a somewhat distant personality and also seemed to be haunted by the success of his peer, Thelonious Monk.

Nichols often lamented his separation from the classical world and was critical of the attitude of other jazz musicians toward it. According to Miller, “He acknowledged the tension between classical and jazz musicians, a tension that he clearly still felt in himself, given his early aspirations in the classical field and his undying respect for its ideals and innovations.” Writing in the Harlem magazine, Rhythm, Nichols said, “The funniest thing to me is the complete realization that our florid 1946 jazzmen are austere creatures who actually sneer at the classicists. It is all an emotional mumble jumble wherein we fools should be big enough to view everything objectively.”

Nichols’s alienation from many of his contemporaries is typified in comments he made to the poet George Moorse: “I used to sit in a lot in the late thirties and forties with the guys who later became known as the bopsters. I guess my playing was even too far out for them. And most of them thought I couldn’t say anything. Of course, in those days I must have looked like a professor, with a starched white shirt. I used to talk about poetry almost as much as I talked about music.”

The vocalist Sheila Jordan recalled that Nichols would “sit in a corner. It wasn’t that he was standoffish, I think he was shy – or maybe his mind was elsewhere…. He was very quiet, stayed to himself, went and stood outside of the club, smoked his cigarets [sic]. I don’t ever remember him even talking to anybody.”

Then there were the comparisons with Monk, who did achieve the widespread recognition that alluded Nichols. According to Miller, both were “similarly influenced by Ellington,” but Monk by 1944 was “already a force among his contemporaries for the formative role that he had played at Minton’s [Playhouse] in shaping the conventions of bebop.” Critic Lawrence Gushee, writing about Nichols’s 1957 Bethlehem album Love Gloom Cash Love in The American Record Guide, said there were “pretty obvious” reasons for comparing Nichols and Monk but concluded that Nichols “is far from the champion that Monk is.” On the other hand, Alfred Lion, co-owner of Blue Note Records, told producer Michael Cuscuna in 1985 that when he first heard Nichols, “I hadn’t been so excited about someone since I first heard Monk.”

Miller’s book is at its best when describing Nichols’s live performances and his willingness, coupled with practical necessity, to play at all kinds of gigs, giving his all even when the style wasn’t his preference. The book only bogs down when Miller goes into unnecessary detail about each selection of Nichols’ recordings.

Dan Morgenstern expressed the tragedy of Herbie Nichols most succinctly in a quote at the beginning of chapter five, which covers the period from 1958-1961. “Herb Nichols,” wrote Morgenstern in the January 1959 issue of Jazz Journal, “has, of course, recorded with Rex Stewart, and with his own trio on two ten-inch Blue Note LPs and on the defunct Hi-Lo label, but all of this is out of circulation, and so is Herb.”