The implementation of feminist theory into the art of jazz criticism is a rational and logical step towards broadening the language and perception of jazz.

For far too long, the voices and gatekeepers of the jazz journalistic realm have embodied the overwhelming dominance of straight, white*, Western, traditionalist males whose navigation through the jazz musical community has resulted in the silencing, diminution, commodification, and cultural appropriation of a Black American art form. White men have dominated the jazz criticism field since the genre’s inception.

White male jazz journalists would argue that the tradition they have overtaken (jazz) has celebrated and supported Black jazz musicians, but this is simply not the case. Not enough has been done in the stretch of nearly a century to address the history of racism, sexism and anti-gay sentiments that plagued early jazz criticism (dominated by white men) and directly combatted the validity and power that jazz musicians had attained through sheer artistic expression, talent and musical innovation.

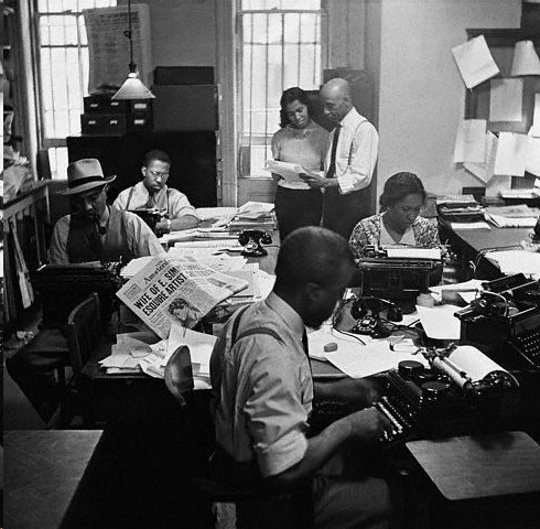

In her paper “The White Reception of Jazz in America,” (African American Review Vol. 38, No. 1, Spring 2004) Maureen Anderson wrote ”From 1917 to 1930 white America was forced to realize that a new form of music, jazz, rising on radio airwaves and appearing in clubs worldwide, was here to stay. At the same time, articles analyzing, judging, appraising, and condemning jazz flooded into publication . . . Motivated by political and racial concerns, many jazz critics during the Harlem Renaissance publicized their dislike of jazz music in order to express their dislike for African Americans.”

She continues, “In striving to analyze and to understand the concepts of jazz music, white critics often hid behind black stereotypes in order to explain the increased fascination the world had with jazz. As magazines first began to recognize jazz, between 1917 and 1920, critics’ principal aim appeared innocently enough to be asking what, exactly, jazz was. Yet, delving deeper into the language of early articles, one soon discovers that the explanations of jazz are also the signs of aggression by white critics . . .”

Though “The White Reception of Jazz in America” mainly focuses on blatant journalistic attacks against Black men, the conversation can be and must be expanded to the erasure and sexist aggression towards women and the white-washing of gay jazz artists due to the fierce and broad disdain toward the majority of non-white and straight musicians, particularly during the early emergence of jazz.

These old modes of criticism have seemed to have been forgotten by current white male jazz critics who now pride themselves and their privilege on “opening doors” for diverse musicians. But minority jazz critics (aspiring and professional) and musicians continue to be very aware of the disparity of diverse voices, looking on as white men may have changed their style of writing, but still hold the keys as gatekeepers, having the power to choose who is brought into the fold.

Therefore, even when white male editors and critics find themselves reaching out to diverse writers, their discrimination can be filtered through charges of women and underrepresented writers not having strong technique or interesting voice, causing writers-of–diversity to become excluded through journalistic standards. This can be a thinly veiled form of exclusion, which white men may not consciously be aware of (and of course, there are white male jazz critics who are undoubtedly aware of their discriminatory preferences).

The traditional voice and standard must change in order for more voices to enter into the field of jazz criticism. Nonetheless, the underrepresented writers who currently fit the voice and mold of the standard voice should not be excluded as a new form of criticism ascends. They should be encouraged to be themselves and not forced to write differently, but rather encouraged to write more freely.

Because we are entering a new post-modern era of the New Jazz Journalism in jazz, and are living in the future that seems distant from the past of fraught gender and racial relations, it is very convenient and arguably quite easy to gloss over the history of racism and the depths of exclusion, particularly during the Jim Crow era towards Black jazz musicians.

Women in jazz, and even more so Black women jazz instrumentalists, composers, arrangers and producers have been rendered nearly invisible in the jazz canon, and the jazz history we know now continues to refuse to acknowledge the multiplicity of talents by many women throughout the entire existence of the art form.

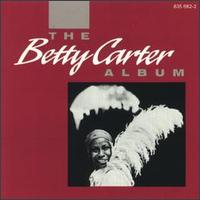

Characteristically the current era of jazz criticism is acutely aware (at least informationally) that women jazz artists write and arrange music for several instruments on their albums, often record and produce their own

music, assemble their own bands, and run record labels — a rare but notable tradition in the efforts of women jazz artists like Betty Carter’s Bet-Car Records (founded in 1970) and Satoko Fujii’s Libra Records (founded in 1997). Carla Bley was breaking ground in 1972 when she founded her WATT label and New Music Distribution Service, the non-profit operation that challenged the gatekeeping endeavors of major label distribution companies, leading to a boom of DIY releases. (Ed. note: Carla Bley was recipient of the Jazz Journalists Association’s Lifetime Achievement in Jazz Award in 2020).

The question becomes whether women jazz instrumentalists and composers should continue to rely on the written tradition of jazz journalism that fails to cover their music often enough and accurately. If men continue to go down this road of sexism and exclusion along with the failure to highlight the breadth and diversity of women’s talents, will women in jazz realize they don’t need men to write about them at all?

With the advent of social media, music streaming sites where women artists can distribute their own music and independent podcasts and journalism platforms that make self-promotion and production extremely accessible, is it any wonder that if cisgender men do not change, women jazz musicians will abandon traditional jazz media altogether? That said, women who find themselves signed to traditional labels and managers may still be groomed to believe that traditional jazz publicity, available though fraught and hard to attain, is something that they need now.

But in the next 20 years, if there is not an obvious transformation of inclusivity — employment! — of women and LGTBQ writers and editors, the established publications and outlets of today may lose key readership. The new generation of fans will not stand for not seeing themselves in the writers, hearing themselves in the voices covering the music.

If jazz criticism continues to recruit and include a small number of women and underrepresented jazz critics without making efforts to train, encourage and rework a sexist landscape that has suppressed these voices out for decades, the would be-critics will either cease to exist altogether or create independent platforms turning away the exclusionary traditional jazz journalism community, run by people of diversity.

It is also possible that underrepresented jazz artists will find alternative ways to promote their music, threatening the future of jazz media staples through no lack of a diversity of voices. That result would solely fall on the shoulders of the men, more specifically white men, who have not worked diligently enough to provide spaces for more than the handful of artists who they consider deserving of praise.

If efforts are made, the future can unfold in a richer, more positive manner as jazz media publications do away with outdated modes of musical selection based on popularity, strong publicity campaigns and male privilege. Women and artists of diversity will find themselves recognized for their breadth of talents. There will have to be incremental yet dramatic changes to the way these artists are described. There should be a wider range of cultural literacy and empathy in the ways they are presented and perceived.

The feminist future of jazz journalism can be imagined in a myriad of forms: As the expansion of the Afro-futurist universe that artists like June

photos by Isio Saba, from the archive of Hat Hut Records Ltd.

Tyson helped create through collaborations with Sun Ra and his Arkestra, for instance, giving glamour and creating a new tone in feature articles that include explorations of the feminist experience and engagements of jazz stars in more well-rounded conversations regarding inclusion. There might be an influx of women and LGTBQ talent whose presence shatters and re-builds the jazz journalistic landscape into a realm of vision and expression derived from their unique experiences, leaving onlookers amazed by innovation that could have never been predicted. One can only speculate about what can transpire. It is impossible to concretely know what the New Jazz Journalism will look and feel like.

If the future is uncertain, the possibility is that the jazz criticism community will alienate a new generation of writers and musicians by not opening its mind to becoming more culturally aware and misunderstanding the metamorphosis of the world around us, which is calling for an entirely new take on jazz and who is making it.

Such alienation can bring nothing but loss – the loss of a generation, the loss of unification, the silencing of growth, advancement and change. The work to avoid this need not be overwhelming. The first step is to admit that the groundwork laid down by sexist, racist and anti-gay writers of the past (1940s to 2000s, say) must be broken, and that the reality of the history of Jim Crow still sits and bellows just below the surface of our amazing community.

With or without effort, jazz criticism will evolve. Will we become caught up in a cycle, where the inclusion and forward movement of the New Jazz Journalism, after a few years of a feminist golden era, falls back into old habits, worn patterns and male domination? Or will we move forward without looking back?

If we do not look back, New Jazz Journalism will usher in a post-reality that will no longer need feminism. Women and LGTBQ will be a part of a new, refreshing season of positive change. Then, with more time, diverse voices will simply be a part of a landscape that will no longer need uproar and lobbying for a better future.

The future will be now, and when that happens advance will come more naturally, as young writers feel safe and receive the same privilege that White men have experienced for many years.

This is, of course, idealistic. There will always be a need for change, for inclusion, for vibrancy and diversity, and the New Jazz Journalism can usher the world of jazz criticism towards addressing these needs for as long as it needs to order to turn idealism into reality. Every human being has the right to embrace jazz. Therefore, every human being must be notified that their voices are vital in the preservation and growth of the art.

Jordannah Elizabeth is a Baltimore-based writer and lecturer.

*white: In keeping with the Associated Press and New York Times’ stylebooks and the author’s preferences, the word “Black” has been capitalized to represent a specific shared cultural history and identity, but “white” not, as ‘ it is an identifier of skin color, not shared experience, and […] white supremacist groups have adopted that convention.’ — ED