By Dave Oliphant

Wings Press, 2012, 200 pps., $19.95 hardcover

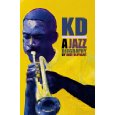

With its rich and dark portrait of Kenny Dorham on the cover, Dave Oliphant’s KD, A Jazz Biography is nicely packaged and neatly presented. To be precise, what it presents itself as is a poem, a 200-page epic on the subject’s involvements and achievements in his 48-year life. Odd, or brilliant, or a combination, depending on one’s take. Certainly intriguing, and worth embracing in an initial encounter on good faith.

Poetry is not by nature linear, and we do not necessarily approach a new work of poetry by going from point A to point B, start to finish, and wrap up the read: we dip into it, and get a feel for tone, scope, and language. On this count, Oliphant has credentials. He is capable of a concise, neat line, with good figures and good punch, much like a Kenny Dorham solo itself. A further dip into the book, however, presents one with some problems. First off, it isn’t, in principle, poetry. In its very title it presents itself as biography, a nonfiction genre. To be blunt, it seems more a kind of glorified notebook emptying. The author is eloquent and knowledgeable, but I believe the pretense of presenting us with a new form of experimental scholarship is a failed one.

If the work does not succeed as art, it should at least succeed in its purported purpose of giving us some good, clear info about Kenny Dorham’s life. And it just doesn’t do that. Dates and facts are presented in vague and elusive ways, more frustrating than artful. There are nice passages where a performance or recording session is described, with evocative similes and metaphors, but they get lost in a shuffle. Oliphant has simply bitten off more than he can chew. If a project such as he has proposed is to work, it requires a certain amount of brilliance, and perhaps even a certain amount of madness. The author lacks either.

In short, when one first dips into the text, the frosting has a nice flavor. A sweet allusiveness ties such a phenomenon as Dorham’s Denmark dates to all manner of thing from Hamlet to the Bohr atom. In a way, jazz scholarship comes of age, underdog Texan Dorham thrown into the headiest mix of cosmopolitan discourse. In a way . . . Then one discovers the cake is stale.

What Oliphant should have given us, and may in fact have been able to do, is a series of lyric poems on the artist, interrelated with the long flights of lyricism we know from Dorham himself. His feel for the artist’s music is not in doubt. In fact, that is precisely the sort of thing Dorham himself would have appreciated, lover of sublime simplicity that he was, and suspicious of the experimental or avant-garde in any form, let alone the failed form of it we get here.