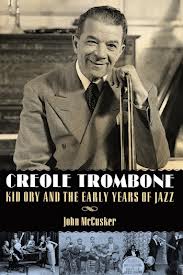

Creole Trombone: Kid Ory and the Early Years of Jazz, by John McCusker. University Press of Mississippi, 2012; 176 pp; $27.97, hardcover; $19.25 Kindle edition.

When it first kicked up dust on New Orleans streets, “ragged time” music was thought of as blatant, uncivilized, and downright immoral. “Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great,” reported the Times Picayune in June of 1918. Ten years later, after Joe Oliver had brought his talking horn to Chicago and Duke Ellington had mixed in Bubber Miley’s squeal and Tricky Sam’s Ya Ya, the jazz genre had been defined.

Slide trombone provided an opening shot. Coming out of John Phillip Sousa’s band, the virtuoso player Arthur Pryor assembled his own orchestra and began putting blustering trombone smears in his arrangements, notably in A Coon Band Contest, recorded May 26, 1906, and in Canhanibalmo Rag, cut May 8, 1911. The mule had got out of the barn—and gone was “polite” American music.

In New Orleans, the escaped-mule cornet players included Buddy Bolden, Joe Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Kid Rena, Chris Kelly, Mutt Carey and others, known for their “monkeyshine” playing.

On trombone, the early Crescent City trendsetter was Edward “Kid” Ory, who had grown up working on the Woodland sugar plantation, and then moved twenty-nine miles downriver to the “City that Care Forgot.” He brought his musical homeboys with him and called his new band by his own name.

Within five years he led one of the defining jazz bands of its time and had begun driving in tent pegs for the New Orleans “tailgate” trombone style—a key element of the new ragtime. In the end, he stood in the jazz pantheon and would help write the new Constitution of American music. Yet until now, we have had no developed story of Ory’s life.

New-Orleans bred John McCusker, for 30 years a photojournalist with the Times-Picayune and a local jazz historian, has written a tightly strung, contemplative biography of that life—revealing not only Ory’s personal story but the music in which it moved. Among other things, McCusker pulls back the curtain on moments Ory shared with Bolden, Oliver, and a young Armstrong, deepening the history. The author explores a lot of corners, until you feel you’ve been around the yard.

Evenings up the river, standing on a bridge, Ory and his buddies made up songs and harmonies—part of a growing national trend in impromptu vocal quartets, McCusker reminds us. Like so many other wide-eyed kids, they built instruments from soapboxes, tin cans, fishing line—whatever they found that worked.

As a teenager, Ory began producing successful band concerts on the plantation. He listened to local string bands, caught old French tunes wafting through the evening air, and heard the brass and concert bands play Old Folks at Home, Whistling Rufus, Home Sweet Home, and Lizard on a Rail. He was supposed to take up sugar production. It was not to be.

When Ory was barely twenty years old, the trumpeting myth Buddy Bolden invited him to join his uptown New Orleans band. Ory was too young, but during the next year he would venture Sundays to Lincoln Park, where he watched the balloon ascensions and heard Bolden and his bootstrap band “call his children home.”

No one had ever heard anything like Bolden’s dance-floor blues. They came from the stomp-down music of the Sanctified churches and the parade “second lines” where, as the early New Orleans guitarist Danny Barker recalled, “No inhibition: everybody lets his self go out to his full physical extent.” To the uptown streets, the freed slaves of Louisiana had brought their African-based ring-shout music, conjuring a religious experience.

Yet at the same time the entrenched Afro-European gens de couleur libres (Creoles of Color), scowling at their uptown cousins, stuck to their straight musical ways of solfege and sight-reading—playing it by the book. If the uptown boys let the mule out of the barn, the downtowners tended the corral fence.

It was in this multi-culture alchemy where Ory came into his own—where he helped make traditional music that swung.

He was not alone. New Orleans was full of bootstrap players—“routiners” they were called—all wanting to ride the wagon, each playing his own street-beat style. But Ory saw that the music was more than off-the-street–that it had provenance. McCusker tells us that besides Bolden’s band, Ory’s favorite was John Robichaux’s society orchestra, which would hold residencies at the Lyric Theatre and La Louisiane restaurant. Ory began to see what Jelly Roll Morton saw—that “You have the finest ideas from the greatest operas, symphonies, and overtures in jazz music.”

Ory found a way to mix the shaky and the sweet. “Ultimately,” writes McCusker, “the combination of Robichaux’s musicality with Bolden’s blues for dancing became the Woodland boys’ template for success: play the rough stuff, but play it sweeter and softer.”

Again, he was not alone. Turn-of-century New Orleans musicians played for dances, parades, picnics, fish fries, and funeral processions—people on their feet rather than in their chairs. Still, the people wanted it sweet.

Dance moved the show. The bassist Pops Foster wrote, “Back in the early days we used to play soft and hot. Most of the time it was so quiet you could hear the people’s feet shufflin’ on the floor.” One observer recalled that when Ory’s colleague Mutt Carey played, “You could hear every instrument. Whenever the band became noisy, Mutt would look back and sideways and say, ‘Sh, sh,’ meaning get down softer. That didn’t stop them from swinging.”

And as Ory later recalled, “We’d get on a street corner, come down softly. People would just run out of the house and start dancing. They liked it soft, not just blasting all the time, you see. They couldn’t hear it way off, you see, and they’d get close, you see. Bring them to me with sweetness, I guess.”

The two sides—uptown and downtown—were finding harmony. Writes McCusker, “While the old divisions between the downtown Creole bands and the uptown gut-bucket bands continued, by 1918 they had become irrelevant because Creoles born in the mid-1880s and after–like Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Jimmie Noone, and the members of the Original Creole Orchestra–fully embraced jazz as their music.” It was as Thoreau had written over sixty years earlier: “One generation abandons the enterprises of another like stranded vessels.”

In 1917, the white Original Dixieland Jass Band (ODJB)—from New Orleans–cut Livery Stable Blues for Victor in New York. It was the first jazz recording ever released, and you could hear Eddie Edwards’ caterwauling trombone pick up where Pryor had left off. Many national listeners had never heard jazz before –and the side “went viral.” The 5-piece ODJB had no violin, so Ory and his partner, Joe Oliver, decided to follow the ODJB’s success and fire their band’s violinist. During these times, the “Dixieland” front line—trumpet, clarinet, and trombone–got its start. Kid Ory was right in the middle of it.

McCusker, however, paints a larger picture: whites and blacks influenced each other. “Oh sure,” he quotes Ory. “You know they, [ODJB leader] La Rocca and those boys, used to stand on the walkways out at Lake Pontchartrain and pick up everything we were doing. I saw them.”

For his research, McCusker had access to an essential source—Ory’s unpublished autobiography. The liberal quotes give new insights into Ory’s relationships with his father, Oliver, Armstrong, and more. The quotes reveal a loving, generous man who took his musical life seriously. They also divulge his feelings about his city and his times.

“I was nothing but a boy from the country, living a clean life while I was growing up, not knowing what was going on in the world, but I want to thank New Orleans and Storyville for opening my eyes to how the rest of the world lived and how people enjoyed themselves in that tough life. It looked as though the people were much happier down there, doing the things they did; which we would call wrong; more so than the people of today having a good time and living a clean life. They were much happier in New Orleans then.”

Anyone who has spent time in New Orleans will understand. The natives will relate to H.L. Mencken: “Immorality: the morality of those who are having a better time.”

Among those who saw further than just “a good time” was a 17-year-old Louis Armstrong, who in 1918 came into Ory’s band, filling the space left by his mentor Joe Oliver. Since he had been seven or eight years old, the young Louis had helped put red beans and rice on his family’s table by selling newspapers, driving coal carts, collecting junk, working on a milk wagon. unloading banana boats, and working construction. His work ethic fueled his talent and ambition.

McCusker establishes the Ory-Armstrong relationship: Ory: “After he joined me, Louis improved so fast it was amazing. He had a wonderful ear and a wonderful memory. All you had to do was to hum or whistle a new tune to him and he’d know it right away….Within six months, everybody in New Orleans knew about him.”

Ory’s band became Louis’ shot-out-of-a-cannon scenario. Within a year the bandleader Fate Marable recruited him to play the Streckfus steamboat orchestras—known among New Orleans musicians as “going to the conservatory.” Writes McCusker, “Armstrong remembered: ‘Fate’s (band) had a wide range and they played all the latest music because they could read at sight. Kid Ory’s band could catch on a tune quickly, and once they had it no one could outplay them. But I wanted to do more than just fake the music all the time because there is more to music than playing just one style.’”

When Ory left his home turf for Los Angeles in 1919, he found a kind of second home; the Great Black Migration had already brought New Orleanians into town. On his first L.A. gig, his band played “to a packed house,” McCusker reports. As would be true in Chicago and New York, few had heard the sound of black New Orleans jazz. Ory’s cornetist, Mutt Carey, recalled that the audience “saw that what they’d been listening to was a lot of tin cans rattlin’, and they fell for our music like a baby falls for milk.” (McC/Ory: 138) On Chicago’s South Side, venue owners had begun hiring only New Orleans musicians.

It was in Santa Monica that the former sugar cane worker and his group—“Ory’s Sunshine Orchestra”—laid down the first grooves by a black Crescent City jazz band. One of the sides, Ory’s Creole Trombone, would forever define the horn’s structural role in the exuberant new American music. As McCusker aptly notes, it is “an ensemble piece from beginning to end with all the players engaged throughout….The out chorus of ‘Ory’s Creole Trombone’ is an outstanding example of New Orleans jazz polyphony”—described by W.A. Mathieu as “Everybody’s playing a different song, but everybody’s playing the same song.”

Ory’s story reached its first flowering when, in 1925, the trombonist was called to Chicago to participate in Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five sessions for Okeh Records—and to join Joe Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators. Both socially and musically, it was full circle. “Those days in Chicago were very happy,” Ory wrote. “We had all played together before, and were friends from the old days.” He had reunited with his two favorite homeboys in the new jazz hub; and he had let his tailgate trombone style, now at maturity, out of the barrel.

McCusker covers the high points of those legendary Hot Five sides—Muskrat Ramble, Heebie Jeebies, King of the Zulus, Struttin’ With Some Barbeque, I’m Not Rough, Savoy Blues, and the justly slower and more swinging re-take of Ory’s Creole Trombone on which, in concert with Armstrong, the trombonist moves the beat more than on his Santa Monica session and further develops his structural underplay. “Here Ory’s contributions are significant,” writes McCusker. “Ory’s tailgate—some would say throwback—style of trombone was a perfect counterpart to the work of Armstrong and (clarinetist) Dodds.”

My own first awareness of Ory came years ago, during the Hot Fives’ take of Armstrong’s Yes, I’m in the Barrel. The tune resounds of a New Orleans funeral, leading with 20 rolling bars of minor-key stop-time (the dirge) by Armstrong, then lifting into a relative-major, four-beat blowout (the second-line parade). As the onslaught reaches the 15th bar (and God knows those all-day New Orleans band parades stopped at plenty of bars), Ory spikes the mix with an urgent, stop-the-show upslide, swinging the parade around a corner.

That slide is really the maturation of Arthur Pryor’s inchoate sound–a huge bee in your ear. Pryor’s is a bit of grandstanding, done more for effect than for musical content.

Ory’s slide however, pushes through the polyphonous mayhem to a blues fourth and drives it, like a stake, into the ground. He opens the Red Sea, and the band marches through. To my ear, it is as defining a note in American music as Beethoven’s syncopated jump-ahead at the 13th bar of the Ode to Joy chorus.

But through it all, Ory apparently never lost his salt-of-the-earth values. When he joined Oliver’s tightly arranged Dixie Syncopators in 1926, McCusker reports, he needed to improve his sight-reading. He contacted a contemporary–Jaroslav Cimera (Ory called him “Schimmery”)—who had played with John Phillip Sousa. The two studied together for just eight months until Ory, with Oliver’s band, left Chicago for the road. Yet with all of his hard-earned success, Ory wrote in his journal, “I’ve always been grateful to Schimmery for what he did for me and I can never forget the man.”

Thank you for a beautiful review of John's telling of my dad's story.

It took many years, through Katrina,& after John's Wife passed.

I miss my dad every dad& now 40 years after we laid him to rest,I still hope to continue

the work I started in 2001.

That is to bring him back home to NOLA.,Many Journalist& Jazz Clubs were on Board.

If it all works, it will 100th anniversary when Louis joined his band.

All the best

Babette Ory

@oryskid twitter

thanks for your note, Babette. Good luck with your project.