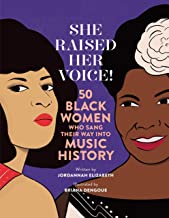

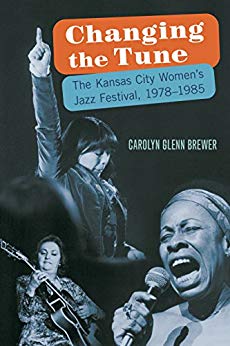

Changing the Tune: The Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival, 1978-1985, by Carolyn Glenn Brewer; University of North Texas Press, 2017; 308 pps; $29.95 hardcover.

The Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival (WJF) was the first jazz festival to feature women musicians. In Changing the Tune, author and music educator Carolyn Glenn Brewer has described the festival performances and provided musical biographies of the major participating artists and less well known performers as well as extensive coverage of the festival’s organizational aspects—fundraising, arranging venues, hiring the performers, and producing the shows. Along with contemporary media and jazz histories, the author’s sources included interviews with the festival founders, musicians, and other contributors, as well as black-and-white photos, footnotes, an index, and a bibliography that includes books, videos, films, sound recordings, and web sites.

The WJF was founded by Carol Comer and Dianne Gregg, jazz journalists and performers in Kansas City. The two friends were returning home from a jazz festival in 1977, grousing about the underrepresentation of women musicians in festivals, when Comer made a “radical” suggestion: Why not put on a women’s jazz festival? They joked about the crazy idea, but then they got serious. Comer and Gregg, portrayed as goal-driven, level-headed, and possessing the inspiration, energy, and time needed to start and sustain the festival, created an organization, sought artists and venues, raised money, and promoted the plan and the first edition of the festival.

For the site, they chose their hometown, centrally located and carrying a celebrated jazz legacy that still had an influence. The Kansas City Jazz Incorporated festival had recently ended after 17 years of well received summertime editions. Some of the younger local musicians, such as Bobby Watson and Pat Metheny, had moved on to bigger cities, but those who stayed, such as Mike Metheny and Paul Smith, were major contributors to starting and sustaining the WJF. The festival incorporated as a nonprofit corporation; the Articles of Incorporation stated its purpose as educating the public about jazz through concerts, workshops, clinics, and “scholarships for students of jazz.” The WJF logo, designed by musician and board member Mike Ning, featured the symbol for woman, ♀.

For advice and resources, Gregg and Comer turned to jazz pianist Marian McPartland, a wholehearted supporter who joined the WJF board, provided contacts, enlisted performers, and signed on to perform. She brought in fellow British expatriate Leonard Feather, the jazz journalist and presenter who had long been supportive of women jazz musicians. For the first few festivals, McPartland performed and Feather announced the shows.

Without a professional fundraiser, the founders used their grant-writing experience to win matching funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). They scored corporate donations from the largest business in town, Hallmark Cards, and from Western Union and several smaller local businesses. The board chose to open the festival to men as well as women performers and audience members; this decision was driven partly by the need to appeal to potential donors, including federal agencies bound by anti-discrimination rules that forbade gender-based exclusion by donation recipients. Although some companies immediately turned down the fundraising requests and other businesses had qualms and ultimately did not donate, the author gave no indication that the theme of women performers was a significant negative point for potential donors. Hands-on promotion and fundraising included selling festival T-shirts and tickets to a basketball game between an all-women team from the city parks and recreation department and an all-men team of jazz musicians.

In March 1978, the first three-day festival opened with workshops by festival performers and jam sessions that attracted aspiring and experienced musicians. The performers at the evening concerts in Memorial Hall included McPartland with her trio and the improvisatory singer Betty Carter backed by the John Hicks trio. Although she was generally well received, some found Carter’s distinctive performing style puzzling. Bandleader, composer, and pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi’s big band performance also won great audience approval, notwithstanding that her band were all men. The All-Stars group, led by McPartland and including Mary Osborne on guitar, Dotty Dodgion on drums, Lynn Milano on bass, Janice Robinson on trombone, and Mary Fettig on alto sax, whom Brewer called the “comfort group,” playing crowd-pleasing standards.

Closing the show was Mary Lou Williams in her piano trio, bringing warm applause. On Sunday, Williams also conducted an afternoon church performance of her composition Mary Lou’s Mass. The author described Williams’s affinity for Kansas City jazz, her mixed feelings about participating in a women’s jazz festival, and her critical attitude and sometimes contentious relations with the more seasoned performers, as well as her history of resentments toward McPartland and Feather.

Despite falling short of the hoped-for 3,500 attendees, the festival drew a crowd of 2,000, hailing from 36 states, who overall were very happy with the event. The author mentioned that when a small group of feminist activists staged a demonstration against in the inclusion of male performers, Margie Adams, the San Francisco-based pianist and feminist, defused their anger by explaining that the festival was planned to include men and that it was “counterproductive” to protest that in light of all the good aspects of the festival. The founders learned the protest and its resolution only after it had happened.

Soon the board started fundraising for the 1979 festival. The NEA repeated its grant offer, and the success of the first festival brought in some companies that had been previously unwilling to take a chance. With the recent spike in oil prices, the festival had to budget more for the performers’ transportation. Off-season fundraising included a successful jazz cruise with Jay McShann.

The author introduces the festival’s artist roster with a section on trombonist and arranger Melba Liston, a Kansas City native who had worked with Dizzy Gillespie. Then in her fifties, Liston came out of retirement to play the WJF. Liston’s career narrative included some difficulties unique to women jazz musicians in the late 1940s through 1960s.

Also in the lineup was established pianist and composer Joanne Brackeen, whom Brewer interviewed. Brackeen’s career story included the challenges of building a jazz career as a woman with four children. Another performer was electric bassist Carol Kaye, a veteran of many pop-song and movie sessions. Among the younger musicians who were taking off were drummer Sue Evans, guitarist Monnette Sudler, and soprano saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom, who was getting notice and some criticism for her improvisations with unusual effects that involved electronics and physical movement onstage. Brewer includes some interview responses from Bloom in which she recalled difficulties with critical acceptance and in getting gigs that she attributed partly to her gender.

Brewer gives high praise to 35-year-old Urszula Dudziak, a Polish jazz singer starting to receive accolades in the U.S., who had a unique performing style deriving partly to traditional music of her native country. The audience was very receptive to the singer, whose band included her husband, jazz violinist Michael Urbaniak.

Cobi Narita, a jazz supporter and promoter of women jazz musicians, was working on presenting a women’s jazz fest in NYC around that time and brought her women’s jazz group to the festival; it included leader Carline Ray; Bloom, who contributed an original composition that went over with the audience; Barbara London on flute; Jill McManus and Amina Claudine Myers on piano, and a number of others. Several other groups played with some overlap in the personnel, including many young women and some older, more seasoned ones. The big-name performer was Carmen McRae, whom Leonard Feather championed.

The third year, 1980, started with the quest for a new venue for the main concerts. As well as audience dissatisfaction with the Memorial Hall’s uncomfortable seats, the festival staff had a disagreement with its management, who claimed that significantly more tickets had been sold than the WJF recorded and consequently took a larger cut than expected. Furthermore, the Equal Rights Amendment had been shelved, so its passage in Kansas was not seen as a draw.

Brewer comments that a number of Missouri residents would not cross over to Kansas to attend a concert at Memorial Hall, a result of ill will between the two states’ residents that lingered from “the Civil War and Border Wars,” and that “far too many potential ticket buyers, particularly African American fans” had made known that they were not comfortable attending concerts at Memorial Hall. (This first mention, one-third through the book, of an essential aspect of the choice of main venue may be puzzling to readers unfamiliar with the relevant regional history.) The main venue was changed to the Music Hall, a more comfortable space on the Missouri side.

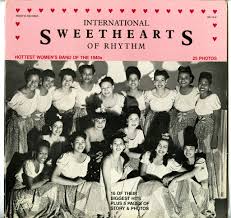

A well-received performance included the surviving members of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, originally a group of young (teenage) women of varied races and backgrounds who traveled on a bus to perform around the US from the late 1930s until 1948, touring with the USO in WWII and winning a DownBeat award. Alto saxophonist Roz Cron was a former Sweetheart who was still active and fairly well known. Carmen McRae returned for a second year, as did Joanne Brackeen, and rising young singer Dianne Reeves performed. A number of the younger and less known players returned after the first festivals in various configurations.

Kansas City declared March a special jazz month in honor of the WJF, which prompted a number of complementary performances by local musicians in clubs and other venues. In the performance category called Top New Talent (TNT), large bands were featured. Also featured was bandleader, composer, and pianist Carla Bley, whom Brewer described as brilliant and entertaining, sometimes puzzling and controversial and not always presenting herself as pro-woman. Singer Cleo Laine was the closing performer.

The chapter includes an update on the WJF scholarship program, which at that point had not been eliciting many entries (only nine for 1980), even though the festival performed outreach to 100 high schools and colleges and placed a notice in the magazine of the National Association of Jazz Educators (NAJE). The judging was blind (based on audio only), and some people were dismayed that the winning entry was the same contestant — a man — who had also won the year before. Brewer quoted the founders’ comment that, essentially, they had done all they could to attract entrants and that potential entrants needed motivate themselves.

By the 1981 festival, the jazz clinics and workshops had become less well attended, but the board decided to keep them on the program. By popular request, a children’s educational workshop was added.

Big-name performers included Ernestine Anderson, a jazz singer with a blues and soul flavor, and Shirley Scott, the spirited hard-bop organist. The other headliners included the Brazilian singer Flora Purim, whom Brewer lauds for her creativity and expressiveness and her inspiration to women.

However, the book recounts that Purim, her husband percussionist Airto Moreira, and their band arrived late because they were caught in a snowstorm as they drove from Los Angeles after diverting the money the WJF had advanced them for plane fare. Without time for a sound check, they were offered the house sound system but instead insisted on using their own cold equipm

ent, assuring serious audio problems.

The couple were unapologetic and made no attempt to communicate with the festival personnel. Moreira was the heavy; during the performance he complained to the audience about the sound quality and blamed it on the WJF. When Comer and Gregg withheld some of the remaining payment because of the transportation money they had misused, Moreira was livid. Although somewhat drawn out, this story incidentally demonstrated the customarily open and honest manner in which the WJF dealt with the festival artists and that they expected to receive in return.

With the 1982 festival, the strength of the performances and the audience size and engagement seemed to approach a peak. After mentioning the tribute to recently deceased Mary Lou Williams, the author turns to big bands, a jazz configuration that had long included few women, perhaps because of the powerful band sound dominated by the brass instruments associated with masculinity.

Weathering some gender-based discrimination, several of the WJF women performers had achieved impressive and career-advancing stints with big-name big bands; Mary Fettig had been the first woman to play with Stan Kenton, and Laurie Frink had played trumpet with Gerry Mulligan’s band. Brewer gives that year’s WJF credit for boosting the success of the first notable contemporary all-women’s big band, Maiden Voyage, which arose from the Ann Patterson ensemble that had been the Bonnie Janofsky-Roz Cron band. The author provides an overview of the big and small groups that were nurtured, encouraged and publicized by the WJF, such as the first WJF Combo Contest winner, Aerial, who used their festival experience as a “springboard” to the Newport Jazz Festival.

The TNT concert included the Swedish group Tintomara, a “European-style progressive jazz band” whose playing was “infused with rock,” as well as Sweet Honey in the Rock, an a cappella group influenced by traditional gospel, and the Bougainvillea, a Boston-based “straight-ahead” gr

oup strong on improvisation. The well attended jam sessions included some for women only, which provided a “welcoming environment for women who were more comfortable playing with other women.” (Presumably the all-women format did not violate the nondiscrimination stricture of the festival’s funding because the sessions were hosted by Crown Center, which was rewarded with crowds of potential shoppers in the mall-like enclosure.)

The house band included the WJF board members Comer, Lynn Riley, Joan Griffith, and Helen Marquette; the bassist and drummer were somewhat overtaxed because there were fewer attendees to spell them. The sessions’ sign-up lists revealed that women had come from Texas, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Georgia, as well as Canada. Singer Blossom Dearie performed in a small intimate hall, where she was very well received. Los Angeles mid-career pianist Joanne Grauer led the All-Stars at the main concert; she had received good reviews for her trio recording in 1957 and later worked as a coach for Hollywood actors with piano scenes; recently she had recorded a fusion-influenced disc. BarbaraCarroll, pianist and secondarily, singer, had also performed at the 1982 festival, and the author recounts her career. Singer Nancy Wilson was another big-name performer at the main concert whose personal and musical story the author tells.

Brewer addresses the general topic of jazz women and marriage, bringing in the stories of older women such as Marian McPartland, Mary Lou Williams, drummer Dottie Dodgion, Barbara Carroll, Blossom Dearie, and Carmen McRae, as well as younger established performers including Carla Bley, Carol Kaye, and Joanne Brackeen. Some of the women had supportive husbands but others met with spousal disapproval of their careers, possibly out of fear of competition; some husbands wanted

their music wives to perform or appear a certain way. Established pianist Jill McManus remarked that she and other women jazz musicians saw marriage as jeopardizing their careers, so that not many were married and most were “functionally single. “At the end of the chapter, the author refers to a “crack of discontent” that appeared when a board member quit because of unhappiness with the conduct and presumptions of a festival videographer and then sent a letter to the other board members that cited various problems and her perception of the WJF as lacking professionalism.

Ahead of the 1983 festival, the WJF was invited to join the KOOL Jazz festival circuit, sponsored by the cigarette company. Although the WJF board was initially attracted to the sponsorship because it would ease the financial pressure that was growing as public funding of the arts was reduced in the 1980s political climate, they ultimately turned down the offer in order to preserve their “autonomy.”

Simultaneously, the board was faced with a lawsuit in conjunction with an injury to the trumpet and flügelhorn player

Ruth Kissane in 1980, when a stage riser collapsed during a performance and seriously fractured her arm and causing long-term impairment of her ability to work in her profession as an accomplished animator in Hollywood. Marian McPartland returned that year as an official WJF performer for the first time since 1979; at age 65 she was the oldest performer in the 1983 festival. A number of college students performed, and the book’s narrative shifts to a history of college-level jazz education, focusing on the accomplishments of renowned jazz educator David Baker, who gave a presentation.

The winning TNT group was Joyspring, who came from the Eastman School’s jazz program, featuring pianist and composer Ellen Rowe, who played originals and standards. The second-place winner was ALIVE! from San Francisco with singer rhiannon. Singer Sheila Jordan with bassist Harvie Swartz also performed in the TNT, which the author remarks seemed strange, as Jordan had started her career in the 1940s and made her first recording in 1962; the duo received an excellent reception and reviews.

Amy Duncan, the pianist for the All-Stars, was also a journalist open with her appraisals of women in jazz and of the festival. Duncan contended that the 1983 festival was behind the times regarding women in jazz, that to draw bigger crowds the festival needed bigger stars such as Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan, that the women-only jams drew fewer players in comparison with the well-attended mixed jams (she partly blamed the lack of female bassists and drummers), and that the festival needed to move more quickly toward reaching the founders’ wish to “make the ‘women’ part of the jazz festival obsolete.”

The All-Stars also included Nadine Jansen on trumpet/flügelhorn, a 54-year-old veteran of jazz, and 20-year-old Carol Chaikin on sax, who had already played with Marian McPartland and with Freddie Hubbard. A discussion of drug use and its negative influence on jazz was introduced by the cancelation of the festival appearance of rising star guitarist Emily Remler, who had a heroin habit that ended her life a few years later.

The author here writes a balanced and believable overview of the pressures and stresses affecting jazz musicians and how they can lead to substance use as a means to relax, feel more energetic and creative, ease stage fright, and please colleagues and club owners; she also touches on pressures unique to or more pronounced for women, such as family responsibilities and bias against women. She refers to the 1981 festival problems with Flora Purim and Airto Moreira as possibly connected to drug use. This chapter closes with an interesting musical biography of singer Anita O’Day, who was one of the big-name performers.

In December 1983, the WJF board announced publicly that there would be no 1984 festival. There had been considerable attrition of the festival board, unsurprising after several years of the demands on the members; the Kissane lawsuit, although settled without financial harm to the festival, had been particularly draining. Many other festival volunteers also needed to take a break.

Comer and Gregg felt exhausted by their leadership roles, and they decided to step down from their positions as officers while remaining active as board members. Several other members felt that Comer and Gregg had become too influential and were holding up the changes needed to revive interest in the festival and improve its flagging finances. Comer and Gregg offered to step down from official leadership roles but to remain involved in the organization.

However, the loss of confidence in the founders became clear in an incident involving the new treasurer. For all the festivals, Comer had routinely given the organization an informal, interest-free loan to tide it over until ticket sales came in. This year, when Comer requested reimbursement, the treasurer challenged her, and other members wondered whether the founder was collecting a salary for an ostensibly volunteer position. The founders’ disappointment and dismay about the members’ professed ignorance of the loan arrangement as part of the general mistrust lessened their surprise when the board asked them to resign for the sake of the festival.

A new president, Julie Hanson, came on to lead the effort to present a 1985 festival. The board hired a consultant to help with revitalization; among the desired outcomes was “willingness to operate organization as a business.” They perceived the need to strengthen advertising, promotion, and long-term planning and to create a “formal community relations plan.” The board rented an office chosen to project professionalism, and they pursued the idea of a paid staff.

The 1985 festival was structured largely as the preceding year’s but with a somewhat smaller number of performances. That year’s scholarship was awarded to pianist and singer Diana Krall, a Berklee College of Music student at the time. Brewer points to Krall’s subsequent success and popularity as validation of the scholarship program and as “yet another way that WJF touched the future of jazz.”

In the board’s quest to bring “new talent” to the festival, they let go of Leonard Feather as the MC and brought in Rosetta Reitz, record company owner and champion of women jazz and blues vocalists past and present. It was harder than anticipated to find “new talent,” and Amy Duncan was again a jam-session leader.

The TNT concert presented a mixture of jazz and rock, Latin, and blues. Group Deuce won the Combo Contest, playing all original material with a Latin influence; the group was led by Jean Findberg and Ellen Seeling and included percussionist Nydia Mata. Joyce Collins, a “seasoned” pianist and vocalist performed a mix of originals and compositions by jazz artists including Mary Lou Williams and Marian McPartland. Local blues singer Ida McBeth warmed up the crowd of 500 with gutsy blues and up-to-date jazz singing. Pianist Judy Roberts returned for the main concert to play a variety of styles. The vocal group Rare Silk, from Boulder, Colorado, impersonated popular acts of the past such as the Andrews Sisters. Toshiko Akiyoshi returned with a trio, with Jay Anderson on bass and Jeff Hirshfield on drums, who played her originals featuring a tribute to her inspiration, Bud Powell. Akiyoshi had played at the first edition of the WJF in 1978, and it turned out that she was playing the last edition of the festival in 1985.

The following December, word went out that the Women’s Jazz Festival had ended. Although some board members wanted to try to continue it, most felt that that was not feasible. Brewer dispassionately lays out the upstart leadership and festival board’s realization that the need to hire professionals with a wide range of expertise not possessed by those running the operation, most of whom were not musicians or industry professionals, could not be met. Members who had decried the original volunteer-driven board and management as messy and unprofessional found that running a professional organization was very costly, and even opening a professional office with one full-time staffer was out of reach.

The current president felt she had done what she could by putting on one last production and leaving the festival solvent. The board donated the remaining funds to the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music. A press release stated that the WJF board was happy that the festival had attained its goal “…to create a market and performance platform of national stature for female jazz performers, and to promote jazz in general.” In January 1986, former board member Mary Hodges wrote to former president Hansen that in a discussion on “Women in Jazz” at a recent NAJE convention, the WJF was praised.

With the Epilogue, the narrative shifts to the present time to touch on the festival presenters’ and performers’ experiences of the festival and how it had affected their lives and careers. In 2015 at the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, there was a viewing and discussion of the 2011 film The Girls in the Band by Judy Chaikin, on the history and current state of women jazz performers and presenters, including those of the WJF. The two WJF founders were in the audience, and the author mentions that Comer continued to perform and teach jazz in KC and that Gregg was active in the organization Young Audiences, which facilitated artistic endeavors for young people, particularly in jazz. A discussion panel included Sherrie Maricle, drummer and cofounder of the longstanding women’s jazz band DIVA, and Lisa Hittle, baritone sax player formerly with the Kenton band and current director of Jazz Studies at Friends University in Wichita. Hittle spoke of her students—both women and men—thinking of and treating women jazz performers no differently from men jazz players. Maricle talked about decades of dealing with negative or skeptical attitudes and how the situation for women musicians had become much better but was far from perfect.

The author notes that women musicians were by then much more prevalent in jazz, from students through internationally recognized groups, such as Wayne Shorter’s 2014 ensemble that included Esperanza Spalding on bass and Geri Allen on piano. She also observes that although Gregg and Comer always contended that they wanted and expected women’s jazz festivals to become unnecessary sometime in the future because “women would be heard as equals,” there will probably continue to be women jazz musicians who prefer to perform mainly with other women. She mentions the women’s jazz festivals that followed the WJF, including the Washington (DC) Women in Jazz Festival and the Women’s Jazz Festival at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in NYC. The celebrated Mary Lou Williams Jazz Festival, started as a women’s festival by pianist, educator, and jazz journalist Billy Taylor in 1996, was drawing criticism for starting to include male performers.

The book concludes with Lisa Hittle’s recollection of attending the festival as an audience member with not much money and “nowhere to stay” and how much it meant to her, even though she was already an accomplished performer. She was struck at how friendly and enthusiastic everyone was, especially at jam sessions.

Before the Epilogue, the book might have been enriched by more insights from WJF performers and other participants on how the festival experience had figured in their own careers and in the general progress of women in jazz. Another shortcoming was that some topics were introduced with less than optimal explanations and follow-up. For example, readers not familiar with Kansas City could be confused by the descriptions that seem to assume a familiarity with the locale, its landmarks, and its jazz clubs in the era of the festival. The WJF scholarship program is introduced with limited details to help the reader fathom why it attracted so few applications—for example, were there restrictions on how, where, and when the recipient could use the award? Finally, the multiplicity of festival performances might have been easier to follow with a listing of the groups and major players and a schedule of the concerts for all the WJF editions.

On the whole, however, the book offers ample and well crafted coverage of the significant aspects of the WJF and on related topics about women jazz musicians. The author effectively points up the strikingly large number of professional (or seriously aspiring) women jazz musicians who were active during the time of the WJF. The festival’s range of genres and styles was impressive, as was the diversity of the musicians in terms of age, geographical, racial, and cultural background. As it becomes more usual for jazz festivals to include significant numbers of women musicians, a book such as Changing the Tune is a significant contribution to understanding the history and current participation of women in jazz.