Years back I wrote an article headlined “Tap as Turf” for the JJA’s print newsletter, discussing how most jazz writers didn’t consider they knew enough about tap dance to cover it. Even Bob Blumenthal, then in the Boston Globe, denied tap was his turf, though he turned me on to entire lp recordings by tap masters Jimmy Slyde and Baby Laurence.

A lot has happened since then — it was the ’90s! — but I still maintain that jazz writers, without any tap vocabulary, can write better about tap dancing than anyone else. Jazz journalists are as authoritative as anybody now writing about tap dancing, because most tap dancers consider themselves “playing their feet to jazz.” As the late, great Gregory Hines (1946-2003) said, “Tap dance is unique because you see the body move and hear the body move.”

Savion Glover at Jimmy Slyde’s weekly Wednesday night session at “La Cave” on Manhattan’s East Side. Photo by Karen Zebulon

I vividly remember a critic for The New York Times asking me the tune of what a younger Savion Glover was dancing to — it was Coltrane’s renowned “My Favorite Things.” On another occasion, at now-gone Sweet Basil’s in NYC, I boldly approached Whitney Balliett of The New Yorker to ask why he stopped writing about tap when he had so eloquently covered Honi Coles, Cholly Atkins of Motown choreography, Baby Laurence and Bunny Briggs, Duke Ellington’s favorite hoofer.

Balliett shrugged and told me to go back to my date. Apparently he was okay with jazz tap being covered by The New Yorker’s dance critic Arlene Croce, who intensely disliked we acoustical tap dancers who were single-footedly creating a tap dance revival. She was in favor of “line” and wrote mostly about ballet. I was crushed when she wrote that my generation, and me above all, were “a lot of white women are clacketing around . . . aping the old black tap masters.” She didn’t like them either.

Ironically, it was Croce’s The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book (1972) on the 1930s’ movies of the great screen duo that made me look up tap in the Yellow Pages (remember the Yellow Pages?) and start to study tap. Hardly anyone covered tap at the time, from the late ‘40s through the mid ‘70s, which Hines, my friend, called “The Great Tap Drought.”

Credit where it’s due: pop culture writer, David Hinckley who wrote for the New York Daily News for 35 years has consistently covered all things tap. This year he wrote the obit headlined “Arthur Duncan Helped Tap Dancing Survive Through the Wilderness,” starting: “The rich and under-appreciated art of American tap dancing lost an intriguing and invaluable pioneer earlier this month with the death of Arthur Duncan.” Prominent publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Smithsonian Magazine and TV News covered 97-year-old Duncan’s death, noting he had found work weekly on television’s long-running The Lawrence Welk Show, and survived — like many jazz musicians — by residing in Europe.

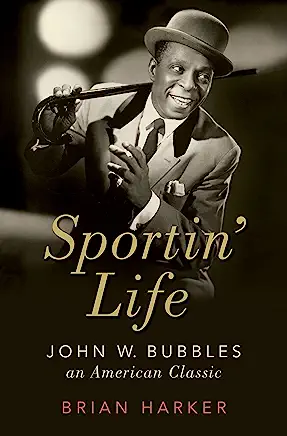

And I once took a class on jazz at New York University with renowned writer Gary Giddins. I discovered he loved John Bubbles. He wrote a long introduction about Bubbles in Brian Harker’s biography of the man, Sportin’ Life.

I knew Bubbles, having brought him to By Word of Foot. Bubbles’ syncopated jazz style influenced tap dancers throughout the globe, in classes, festivals and workshops. I also went out to study with him in 1982 to prove to the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) to prove that Bubbles was still relevant though he was paralyzed from his waist down. He taught me with his fingers tapping.

Bubbles and Jane thumb-wrestling

My cohorts and I had studied with the Old Masters like Bubbles and Duncan when we started self producing shows in the ‘70s and ‘80s, leading to a tap revival or renaissance. In 1978, a New York Times review urged, “break down the doors if you have to” to see my show in a SoHo loft. Jazz impresarios Max Gordon and the Public Theater’s Joe Papp had to climb five flights of stairs to check it out, because the elevator was broken — but we were eventually booked in their venues. Slowly, there was work again for tap dancers, young and old.

In fact, the old masters never voluntarily retired. They had found other jobs in other professions. But my generation — including black and white women, and men, too — organized the older tap masters and young people of mixed cultures to perform together. We got media attention with the slogan “Tap is Back.” And it came back with many of the younger performers studying tap’s original roots in jazz.

[Regarding my talking and singing while tapping: Working in Florida in the ‘90s, I met a wonderful tap dancer called “Tampa Jane.” I taught her mainly the kind of tap the hoofers had taught me, inspired by Father of Rhythm Tap, John Bubbles. Tampa Jane told me that before my classes, she had never before experienced anyone “scatting a class.” Referring to how I taught tap rhythmically, actually singing (a cappella) the musical tune with syllables and not just employing such typical tap vocabulary as shuffle, flap, and ball change, she said I had “changed her life completely. You taught with your voice,” she exclaimed at what was evidently for her a novelty. But Gregory Hines “scatted the class,” and even had students sing the song along with him.]

The accessibility of films of tap’s Golden Age icons — besides Astaire and Rogers, I’ll mention Bill Robinson, Eleanor Powell, the Nicholas Brothers and Shirley Temple (#1 box office star of the Depression) — played a major role in educating dancers and the public, as has, surprisingly interactive formats like zoom. In fact, Trina Josdal, an artistic director of Vintage Taps, discovered me in a Zoom session, and with chutzpah, called me to teach her Toronto company using that interactive platform — which became a real high point of my experience of the pandemic.

A couple years later, with Covid-19 suppressed and following her visits to New York, Josdal and her joined-at-the-hip partner Amy Lintunen offered me a week-long Toronto residency with Vintage Taps (June 20-23, 2023). I didn’t dance — I had popped my knee — but there was a program based on my book Shoot Me While I’m Happy — Memories from the Tap Goddess of the Lower East Side

and two tap shows about me with live musicians playing “I’m Beginning to See the Light,” “Stepping Out,” “I Wanna Be Happy,” “I Thought About You,” “Some Day My Prince Will Come” and other standards, all jazz choreography and improv.

The Toronto dancers took me to Grossman’s Tavern, one of the city’s longest-running live music venues, self-described “Home of the Blues and Jazz.” There, the locally-based Happy Pals New Orleans Party Orchestra, featured every Saturday at Grossman’s for more than 40 years, was having fun with New Orleans repertoire. I got up with my cane as the orchestra brought the show to an end with “The Shim Sham,” tap’s national anthem. I learned there’s a jazz band with dancers swinging every night.

Another night called “Docs and Talks” included footage from the first ever week-long tap festival of 1980, By Word of Foot, produced by my non-profit Changing Times Tap. The “doc” included jazz tap dance masters teaching to the accompaniment of pianists Ram Ramirez and Dick Hyman. I spoke anecdotally about the footage and held a Q&A session that lasted into the evening.

I also met Travis Knights, who, like me, has been documenting and interviewing tap dancers of my generation. By Word of Foot set the tone for tap festivals “tappening” globally, always accompanied by jazz musicians.

Says Trina Josdal, co-Artistic Director of Vintage Taps: “The skills and

and musicality of tap dancers should be appreciated because it has historically been that symbiotic relationship that pushed the syncopation and swing of jazz. Brian Harker writes Sportin’ Life about the time from 1926–1927 where Louis Armstrong spent every night playing with many hoofers, including John Bubbles who ‘played every step they made’ . . . ‘Instead of the dancers working out a routine to Armstrong’s music, it was the other way around.’ In 1926, Armstrong recorded ‘Big Butter and Egg Man,’ the first to give evidence of his rhythmic breakthrough. In this solo, the old ragtime cliches give way to constantly changing patterns – the kind you’d expect from someone shadowing a pair of rhythm tappers.

“So tap dancers who dance to jazz should be covered because they are constantly pushing the rhythmical boundaries of jazz music. I’m not saying every band needs a tap dancer, but imagine if you had a jazz band where a journalist covered all the instruments but the drummer. As preposterous as it would be for them to not review a jazz band because they have a percussionist, is how it feels to not review a tap dancer, one of the earliest players of jazz.”

Adds Amy Lintunen, Co-Artistic Director of Vintage Taps:

“If tap dance isn’t important to jazz/jazz history then why did Marshall Stearns make a point of interviewing as many tap dancers as he could for Jazz Dance?

“Tap Dancers are often put in the entertainment category and not considered the serious musician they actually are. Listen to Jimmy Slyde and tell me he’s not a member of the band. Listen to Baby Laurence and tell me that tap dance improvisation is not as difficult as jazz improv when you are having to account for movement, momentum and the technique that lives inside all the vocabulary. I think tap improv is more difficult . . .If tap dance is not jazz, tell me why is Ian Berg at Berkeley in the jazz program and his instrument are his tap shoes? Tap dance is jazz. It embodies everything that jazz is. Wikipedia defines jazz as: Jazz is characterized by swing and blue notes, complex chords, call and response vocals, polyrhythms and improvisation. Jazz has roots in European harmony and African rhythmic rituals.”

When I returned to New York from my Vintage Tap residency, the 22-year old Tap City festival, organized by Tony Waag, director of the American Tap Dance Foundation director, began. An excerpt from Tony’s email to me:

When I returned to New York from my Vintage Tap residency, the 22-year old Tap City festival, organized by Tony Waag, director of the American Tap Dance Foundation director, began. An excerpt from Tony’s email to me:

“Today, tap dance continues to be practiced, taught and developed as an international art form and it is being interpreted, explored and presented around the globe.

“The popularity of Tap Dance has risen significantly since the mid-seventies. Our nation has slowly been educated about the history of Tap and its significance as a legitimate art-form worthy of examination and perpetuation! Its history is very complicated, and it is absolutely fascinating. It parallels our nations issues with racism, sexism and ageism. It basically grew up from a folk dance, and then went onto the stage and in films, and it is now considered and recognized as a high art! Just like Jazz music!”