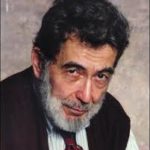

Editor’s note: Nat Hentoff, jazz journalist, civil rights advocate and JJA Lifetime Achievement Award honoree, died January 7, 2017. Christine Passarella, educator and founder of Kids for Coltrane, was among those benefitting from Nat’s attentions and support.

A Writer Supreme, by Christine Passarella

In a New York City Greenwich Village apartment sat a man deeply absorbed in banging out articles about social justice, the Constitution, human rights, and his dear friends in jazz for the Village Voice and the Wall Street Journal. He worked on a typewriter, as modern technology was not for him. One day in 2007 he noticed the name John Coltrane in a press release about a Kids for Coltrane school show I was doing with my second grade students. And this is when American historian, author, journalist and National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master recipient Nat Hentoff gave angel wings to my work in elementary and middle school education with a focus on teaching through the arts.

He called me, curious about a New York City school in which youngsters were being uplifted by the music of master saxophonist and legend John Coltrane. “This is Nat Hentoff, I write for the Wall Street Journal and the Village Voice,” his velvety, strong voice started, adding that John had been a dear friend of his, who he knew very well.

After a brief conversation he asked me a few pointed questions. He wanted to know how and when John Coltrane had come to inspire my students. I was to tell him which songs I worked with and what other projects I was doing. He asked me to explain my philosophy in education. Mr. Hentoff directed me to write down my answers and mail them to his home address.

I called the document I sent to him “Notes for Nat” and it turned out to be the first of many “Notes for Nat” that found their way to his apartment. I wrote of my belief that all students deserved to be treated with respect and my mission to create learning environments for children that inspired them to soar. Guided by research coming out of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, and Teachers College, Columbia University, Dr. Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences, Peter Senge’s, Fifth Discipline Theory, hopes from work coming out of the George Lucas Foundation, my own experience at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and with artful thinking in my classrooms, I intended to create loving educational environments where it was natural to bring the arts into the other disciplines. Giving music literacy lessons, I had discovered the importance of the music of John Coltrane.

My epiphany took place in the classroom with the children. The pure humanity in Coltrane’s music made it the perfect vehicle for which I’d been searching my entire career. Inherent in it I found an extraordinary interdisciplinary approach to education for children.

My first “Notes for Nat” seeded a bond between a writer who fought for justice with linguistic brilliance and courage and myself, a dedicated school teacher. When Nat called back after reading my words about uplifting learning environments and my deep frustration when any educational system crushed children’s souls and dreams, he asked me, “This is not just about music, is it, Christine?”

I replied, “It is about fighting for the rights of each individual child, as we are uplifted by the music and spirit of John Coltrane. I’ve come to focus on using jazz to teach children about American history, equality, character education and the arts. Such a program helps children develop a foundation from which to become innovative and vital global citizens.”

Nat wrote an article about Kids for Coltrane in the Wall Street Journal, August 21, 2008. He elated me, saying that bringing Kids for Coltrane to national attention was one of the most important things he had ever done. Eventually he included a chapter about my work in his book At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years on the Scene. “I will make it the last chapter,” he told me when he was preparing the manuscript, “as it gives me hope for the future.”

It became clear to me that both Nat and Coltrane were supporting me to do important educational work. The program soared, but the New York City system in which I found myself seemed constricting, with policies getting closer and closer to Common Core practices, a skill-and-drill environment. The days of teaching through the arts seemed gone. I retired early from the city’s Department of Education system, but vowed to continue my work and that is exactly what I’m doing. Nat knew I would.

Kids for Coltrane has taken different forms in addition to my in school programs, I developed after-school programs, library and community center workshops and presently am planning jazz clubs workshops for children and their parents. Nat was always proud of what I did, and stoked the fire Coltrane had lit under me.

Coltrane had said, “When there is something we think could be better, we must make an effort to try and make it better. It is the same socially, musically, politically….in any department of our lives.” I tried to walk that walk. I discovered that just weeks before the great saxophonist passed away he’d been in the early stages of creating a club for children in which they could listen to music and learn about life. I felt my work was a continuation of his plan.

Nat and I understood one another, so he and I came to speak intermittently year after year about education, his legendary musician friends, and his beautiful family. I reveled in his stories, and was honored that this great man showed me such deep respect.

Nat Hentoff was born in the 1920s in Boston, a time and place where Jewish people were not always treated justly, as he wrote in his memoir Boston Boy. He was a gifted young man who attended Boston Latin School. Jazz music soon became his love after he heard Artie Shaw play “Nightmare.”

As his passionate pursuit of the music continued, jazz musicians embraced Nat throughout his life.

Besides Coltrane, he became close to Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Quincy Jones, Lester Young, Cecil Taylor and the list goes on and on. African-American jazz musicians felt this Jewish-American writer’s great empathy and respect for the lives they’d lived and music they’d created. Nat wanted to learn from them and share their life stories, which they played with love through their instruments and sometimes spoke of to him, as in his classic book Hear Me Talkin’ To You (oral histories, in collaboration with Nat Shapiro).

I got to hear Nat’s own stories first hand, right through the telephone. He loved talking about his granddaughter Ruby who was learning to play the piano, and his daughter Jessica, one of the founders of the Big Apple Circus. There were heart-warming tales about his close buddy Q — Quincy Jones, who he told about my work! It was edifying to learn about his relationship with civil rights giants such as Malcolm X.

Yes, Nat had earned Malcolm’s confidence. The two first met for an interview. As Nat told it, Malcolm had him wait for over a half hour in a Nation of Islam-owned eatery as a song titled “A White Man’s Heaven Is A Black Man’s Hell” played on the jukebox, over and over. Finally Malcolm made himself known to Nat and the gentlemen spoke that day for over two hours.

Something happened during that discussion which connected them; they became friends as they worked toward social justice over the years. Nat saw Malcom just days before his assassination, and remembered Malcolm stating he did not have much longer to live. Nat was in Washington Square Park sitting on a bench listening to the radio, with his daughter in a stroller, when he learned about Malcom’s tragic death.

In 2014 the documentary The Pleasures of Being Out of Step honoring Nat was released. During my Coltranean journey I became close friends with American philosopher, educator, writer and social justice superman Dr. Cornel West.

“Cornel, would you like to meet my mentor Nat Hentoff and attend the New York opening of the film?”

“Absolutely!” was his reply.

After the film Nat made a statement to the audience about the importance of my work! I was on cloud nine. Cornel looked at me, and I was beaming with pride. We made our way down to Nat, sitting in a wheelchair in the front row. One of his sons announced our arrival; then and there I witnessed the meeting of two brilliant civil rights activists, who fully respected one another and shared that uplift Coltrane gave people listening to his music. I was stunned by the beauty of the moment, and felt my journey was written in the stars.

Sadly, Nat has passed away. He was 91 years old, a loving husband to his wife Margot, a dedicated father to his two daughters and his two sons. How blessed they are to have been loved by him. I cannot imagine the loss they feel, but I know that his love for them will always keep them strong.

I want to tell his family that Nat changed my life forever, too, because he had the ability to see into my heart, mind and soul. He would often reference Duke Ellington’s song entitled “What Am I Here for?” as we both pondered life.

“You know exactly what you are here for Christine,” he confidently said to me. He understood that I had to follow my bliss and calling as an educator uplifted by John Coltrane’s life, music and spirit.

Nat was truly a hero to me and my students. Now each year we award the Kids for Coltrane Nat Hentoff Humanitarian Award to an outstanding adult who is inspiring children. Nat was very pleased to be the first recipient. His work will live through Kids for Coltrane, as he breathed his rare essence into my dreams and the dreams of so many young people. Nat was thrilled to discover in 2015 that the Kids for Coltrane would be included in the DVD version of the documentary film Chasing Trane.

I will forever be humbled and grateful to Nat Hentoff for seeing something inside of me, and saying “Who knows what else will come of your Kids for Coltrane in the future?” With gratitude I write this of my mentor, with A Love Supreme.

Postscript: On January 20, photographer Charles “Chuck” Stewart died (1927 – 2017). Stewart’s images of John Coltrane enhanced some of the same Impulse! albums graced by Nat Hentoff’s liner notes. Stewart was recipient of the JJA’s 2008 Lona Foote-Bob Stewart Award for Excellence in Photography.