A new Romanian film documents the man behind invaluable, Quixotic Leo Records, and reunited the author with Leo Feigin after 30 years.

In 2019 Ioana Grigore, a student at Bucharest’s Theatre and Film University, made her debut with a one-hour film titled Creativ. It was a documentary about the eponymous band, which had established itself as the main landmark of Romania’s jazz avant-garde during the terminal decade of the country’s post-war totalitarian regime.

Persevering for five years in the direction initiated by Creativ, Grigore has just premiered her second cinematographic-musical project. Entitled Leo Records. Strictly for our Friends, it was launched in October at the 2024 edition of the ASTRA Cinema Festival in Sibiu, the enchanting city of Romania’s Transylvania Province, home to the country’s legendary jazz festival. I was able to attend, and complete a circle of connection begun three decades ago.

Here’s the story: the group Creativ, initiated by Constanța-born pianist Harry Tavitian towards the end of the 1970s, had as its nucleus his connection with drummer/percussionist Corneliu Stroe. Their fervent collaboration, sporadically augmented by other valuable musicians, lasted until 2002. Unfortunately, in 2017 Stroe left the stage of life for good.

The film Creativ – to which I was invited to contribute as a friend and consistent promoter of the Creativ band – is explicitly dedicated to Stroe, an unforgettable artist and man. Among the epic threads that I suggested as potential themes to director Grigore was an extravagant history of producing the first two Romanian avant-garde jazz albums in the West, with the iconoclasts Harry and Corneliu as protagonists. The LPs were issued by Leo Feigin’s London-based Leo Records under the titles Horizons (LR 124) and Transilvanian Suite (LR 132) in 1985 and ’86, respectively.

Actually, as Romania’s representative in the editorial office of Jazz Forum, the magazine edited in Warsaw by the International Jazz Federation (IJF), I had managed to establish a connection (even despite the global Cold War pressures) with Feigin. His label specialized in the release of albums by quasi-unknown innovative jazz creators from nations held hostage by the odious Iron Curtain.

I had been impressed by Feigin’s productions, through which he made known to the “free world” masterpieces such as Live in East Berlin, by the unforgettable Ganelin Trio. The creative collaboration of

pianist Vyacheslav Ganelin, multi-reedsman and horn-player Vladimir Chekasin and drummer and percussionist Vladimir Tarasov, the group had established itself in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital still under Soviet occupation.(Currently, Ganelin is Israel’s supreme jazz authority, a professor at the Jerusalem Academy of Music, while Tarasov and Chekasin, his ex-companions, coordinate a veritable national jazz movement in their adopted homeland, Lithuania).

I sensed that Leo Feigin might also be interested in the achievements of native Romanian creative musicians, although no one would have given them the chance to become a cultural “export” under the isolationism imposed on Romania since 1971 by its dictator, and so I contacted him. After initial correspondence in which I attested to Creativ’s qualities, I received an agreement in principle from Leo regarding some possibilities which stimulated my inventiveness. As author (with the invaluable help of editor Carmen Cristian) of the Eseu Jazz show at Radio Cluj, I arranged a recording session for the Creativ band in that station’s studio (benefitting there from the intellectual openness of its manager, writer Vasile Rebreanu). A true feat, considering that the distance between Constanța on the Black Sea coast and Cluj, set amid the plain of central Transylvania, near the Western Carpathian Mountains, was long and difficult to travel, and the dictator complicated things even more through austerity measures (including reducing fuel consumption for cars, buses, trains, etc.).

Meanwhile, during that period the Sibiu Jazz Festival (Romania’s oldest, founded in 1969) had gained such momentum that the peak of the 1981 edition consisted of an overwhelming recital by the Ganelin Trio! Taking advantage of the goodwill of the Sibiu organizers – led by Professor Nicolae Ionescu – and also of the Radio Romania team (where Florian Lungu coordinated the jazz section), I also obtained the magnetic tapes of the concerts performed by Creativ on the Sibiu festival stage.

Transporting those precious documents over our borders was, in principle, prohibited. That being so, we have never found out (neither I nor Leo Feigin), who had passed them on to him for production in London or how they’d done it. The assumption communicated by Corneliu to me at the time was that certain young Cypriots, students in Romania, would have taken them to their country (a former British colony), and would have shipped them from there to London. Anyway – not being a dissident literary work, of the Solzhenitsyn or Paul Goma category – the respective tapes were eventually processed and edited into the form of the two above-mentioned albums, asserting their historical value internationally, not only within Romanian jazz.

I had heard Feigin’s voice for the first time in 1984, on the phone from the Swedish Jazz Federation‘s headquarters in Stockholm, on the occasion of my participation in the IJF congress in Norrkoping.

To get there I had used the passport, after an exhaustingly long procedure, thanks only to my status as a member of Romania’s Writers’ Union, I had obtained in 1981. In those conversations we managed to finalize matters related to the track lists and the two albums’ covers. Leo entrusted me as well with the mission of writing the liner notes for the second LP. Another sign of invigorating confidence from his part was the invitation he addressed to me, to conceive two extensive essays for the collective volume he would publish in 1986 titled Russian Jazz New Identity (Quartet Books, London).

My long-awaited direct meeting with Feigin did not happen until 1994, when I toured England, Scotland, Ireland and Northern Ireland, uttering my poetic texts in interaction with Alan Tomlinson (trombone master and prominent figure of the British musical avant-garde), as the first step for the creation of my Jazzographics group, which would also include Tavitian and Stroe. Leo had generously invited me to his home near London’s Crystal Palace, where he lived with his young wife, Lora. I was also to be his guest on the jazz program he made for the BBC Russian Department. It was there that he introduced me to Efim Barban, the respected “guru” of Russian-speaking jazz studies, who did me the honor of inviting me as well to his show in the same studio. Another gesture of solidarity was Leo’s appearance at my spoken word performance of own poems in the company of a devastating improvising trio: Tomlinson, trombone; Roger Turner, percussion; Dave Tucker, experimental guitar. The show was held at the Priory Arms, a prominent venue for London’s non-conformist jazz scene at the end of the 20th century.

It’s no wonder that Feigin’s biography inspired an entire new film for Ioana Grigore, after she had included in Creativ some sequences recorded in the small town of Kingskerswell on the south-west coast of England, where her protagonist had retired to old age, in a life that has taken him a great distance.

Leo Feigin was born in 1938 in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad). In his youth, he was a performance athlete – a high jumper.

He became involved in the world of jazz as a young man, and after the famed 1967 jazz festival in Tallinn he met Willis Conover, who had accompanied Charles Lloyd’s Quartet, with Keith Jarrett, Ron McClure and Jack DeJohnette, to the Soviet Union. The group even performed in Romania during the same tour.

Conover was the creator of the legendary Voice of America jazz broadcasts avidly listened to in countries with dictatorial regimes at the time from the mid-1950s to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But in those years, contacts between Soviet citizens and foreigners continued to be viewed with suspicion by the state security organs. It is no wonder that in his autobiographical volume All That Jazz, issued by Amfora Publishing House in St. Petersburg in 2009, Feigin devotes an entire chapter to the infamous KGB, evoking conclusive moments of the surveillance, harassment, prohibitions, or threats to which it subjected him for years. Lastly, in 1973 the KGB suggested to Feigin that he would be preferable to emigrate to Israel rather than live under the threat of possible exile to Siberia. A few weeks after landing in Tel Aviv, he found in a local Russian-language newspaper a job offer from the BBC’s Russian Department as a translator and broadcaster. In Britain’s capital he had the chance to inaugurate his weekly jazz program, presented for years under the radio pseudonym Alexey Leonidov.

In 1978 a tape of Ganelin Trio’s music was smuggled out of the USSR and sent to Feigin, with a note saying “Phenomenal!” Although that masterpiece aroused the astonishment and admiration of Western experts to whom the BBC editor proposed it for post-production and release, no record company had the flair to transfer it to vinyl. From such circumstances, in 1979, Leo Records was born.

What began as a project limited to a single release became a venture of endurance. For 45 years now, Leo has run one of the world’s most notable record companies, although – as is well known – the uncompromising aesthetic he promotes has no chance of commercial success. His advantage over his Western-born competitors lies in his global vision of the avant-garde phenomenon’s evolution. The mission he undertook with LeoRecords was to document, safeguard and disseminate the invaluable contribution to the evolution of jazz by musicians originating from the totalitarian space.

Among the anthological albums with musicians from the Eastern Bloc edited by Leo Feigin for his record label, I would mention in addition to those above-named: Ganelin Trio’s masterstrokes, such as Con Anima, Concerto Grosso, Poco-a-poco, Ancora da Capo, Con Affetto, Old Bottles…, Strictly for Our Friends, Encores, Vide, Ttaaango In Nickelsdorf, New Wine; the three anthologies entitled Golden Years of the Soviet New Jazz, containing four albums each; Vladimir Chekasin’s own projects, e.g. New Vitality, Exercises, Nostalgia; Sergey Kuryochin’s The Ways of Freedom, Pop Mechanics, Divine Madness, Subway Culture; Anatoly Vapirov’s Sentenced to Silence, Invocations; Valentina Ponomareva’s Fortune Teller; Petras Vysniauskas’s Viennese Concert; Homo Liber Quartet’s Siberian 4; Jazz Group Arhangelsk’s Pilgrims.

Quite often Leo facilitated fruitful meetings between musicians of Eastern European origin and prominent figures from other realms. Thus, I was impressed by two of the albums made by reedsman Keshavan Maslak (American, born into a family of Ukrainian immigrants): Romance in the Big City, in duet with Paul Bley, and Excuse Me, Mr. Satie, with Japanese pianist Katsuyuki Itakura;

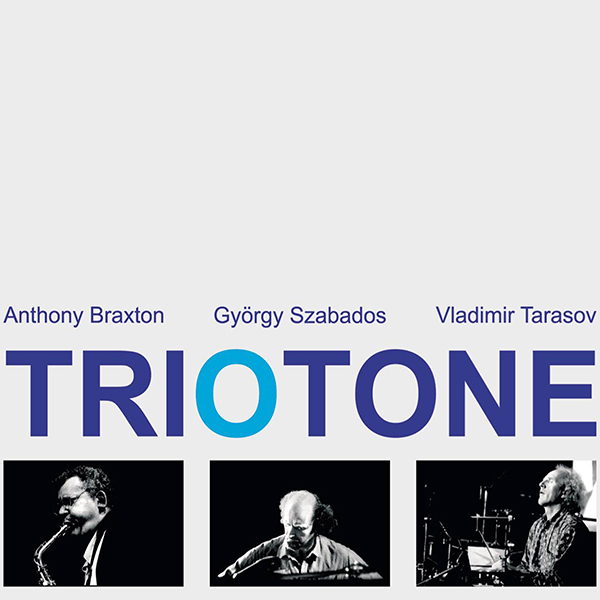

Likewise, the album Triotone bringing together Anthony Braxton with Hungarian pianist György Szabados and Russian-Lithuanian percussionist Tarasov; or the Upside Down album, performed by Russian accordionist Evelyn Petrova in duet with Romanian based-in-England violinist Alexander Balanescu; and yet another striking combination: the revered Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stanko, in the company of Irish guitarist Mark O’Leary and the utterly versatile American drummer Billy Hart on the LR 445 CD entitled Levitation.

As I’ve said above, Ioana was kind enough to invite me to the ASTRA Festival premiere screening of Leo Records. Strictly for our Friends. A unique occasion to enjoy a reunion with my old comrade of ideas, who has now reached a venerable age. Despite his 86 years, Leo Feigin stoically endured the grueling transcontinental flight from England, and delighted us with his lucid, vivacious, seductive presence.

I would say that his main asset in confronting existential vicissitudes is a personal combination of (self)irony and humor, sometimes cynical but always comforting. In a sequence filmed in his home on the British Atlantic coast, he leads Ioana through the countless shelves and crates in which records from his company’s catalog, which has reached many a hundred titles, are stored. When he comes across an empty crate, he bursts into bitter laughter and tells Ioana: “See? This is how success is measured: if everything in a crate has been sold, it means that the record was successful.“ It’s just that in today’s world overwhelmed by mediocrity, most of the boxes in the warehouse are crammed with unsold records.

While living under Soviet totalitarianism, Leo had forged – like some peers of his generation – an idealism expressed through his devotion to jazz. Arriving in the hyper-mercantile British society marked by Thatcherism, he reacted by founding a non-commercial record label!

In the preface to his aforementioned autobiography, Feigin confesses: ‘‘From the very beginning of my career as a producer, I have dealt with music that, as I believe, is ahead of its time. This circumstance alone makes it intended for a minority who understand the music of tomorrow. It cannot, in principle, be sold in large quantities. Nevertheless, I have been happy to publish precisely this kind of music for the smallest audience with advanced tastes, and to help musicians document their works.”

In Sibiu, Feigin was accompanied by his smiling daughter Sasha, as well as the duo of British improvisers Carolyn Hume/piano and Paul May/drums, who gave a recital in line with the theme of the film, after the successful screening in Thalia Hall. My heartfelt reencounter with Leo Feigin, after precisely three decades, strengthened my faith in the redemptive virtues of music.

Although Leo has always lived far away from me, through our common elective affinities and thanks to an amazing mutual empathy, our friendship has persisted, albeit mostly as a constant virtuality. Such a feeling of unity of action can strengthen a man’s mind, defying the horrors that seem to overwhelm us.