I remember my first visit to the United States well. The year was 2018. My colleagues and I had just returned from the funeral of trumpeter Igor Bourco, one of the most important Russian jazz musicians, the creator of one of the

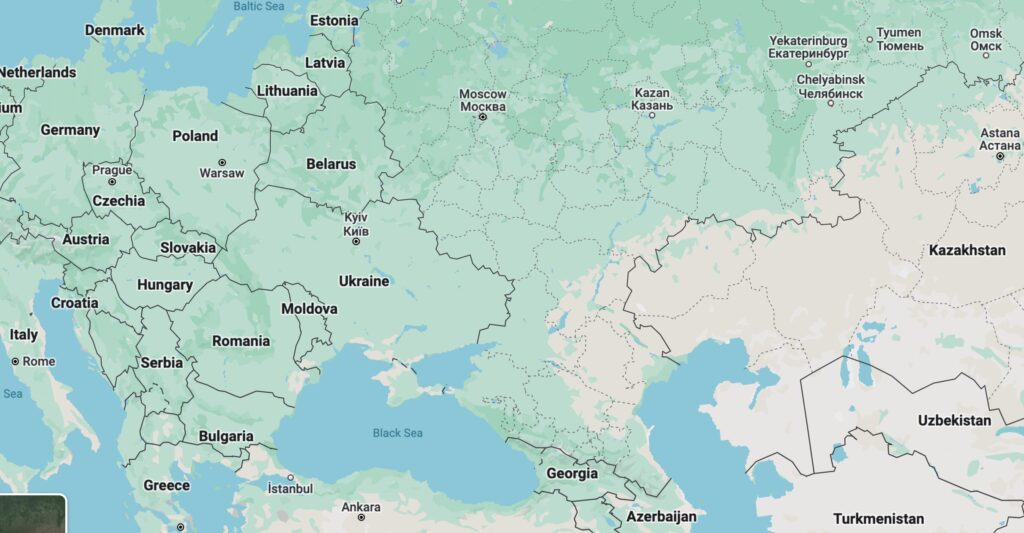

oldest ensembles of traditional jazz, “Uralskiy Dixieland” and founder of the Chelyabinsk International Jazz Festival, “What a Wonderful World,” when I received an invitation to visit America to participate in the State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program.

Sadness and joy often go hand in hand. Bourco had played a significant role in my life. Many years ago he’d taken me on stage, entrusted me with hosting concerts and festivals. So it was a strange coincidence that on this grievous day I had gotten such a gift.

For wasn’t it a gift to spend almost a month going to the homeland of jazz, visiting several states, gaining new knowledge in performing arts management, meeting with outstanding figures of theater, music, ballet?! After that momentous trip, I decided that I definitely needed to return to the US in order to immerse myself in the realm of jazz.

A new journey across the ocean was made possible only five years later. In 2023, I was working at the Chelyabinsk State Philharmonic as a musicologist, concert presenter, director on tours in Russia and abroad of the Uralskiy Dixieland jazz ensemble, jazz festival art director, teacher of “History of Modern Mass Music” and “Music Industry Management” at the Institute of Arts. I’d published dozens of articles and a large book about jazz. It was time to open a new chapter and try to become an international specialist. Why not share my knowledge with a wider audience? Maybe I could also embrace the role of a representative of Russian culture and jazz. I understand that may seem a bit melodramatic, but jazz does not exist without passion. This type of music cannot accept indifference.

Since 1972, the Fulbright International Academic Exchange Program for artists and scientists has operated in Russia. Applying for participation, I offered my lecture course on Soviet jazz as a project proposal. My friends laughed, remembering the old Russian saying “They don’t take samovars to Tula” (similar to “They don’t bring coal to Newcastle”), hinting that, to put it mildly, America has no shortage of jazz experts. Moreover, some music colleges in the USA have their own experts in the field of Soviet art. For example, Gabrielle Cornish, Assistant Professor of Musicology at the University of Wisconsin has dedicated her work to the post-Stalin period in the USSR.

However, my course aroused some interest. Several universities sent positive responses. Kimberly Hannon Teal, a professor at the University of North Texas, recalled that the UNT student orchestra One O’Clock Lab Band successfully toured the Soviet Union in 1976. I considered this as proof that the path I had chosen was right. So I crossed my fingers and hoped to be the first Russian Jazz Fulbrighter!

To be honest, the dramatic events of the external socio-political context fueled my anxiety surrounding the trip. I thought that no one in the world could predict what would happen tomorrow or when there would be a detente in international relations. It was difficult to say whether it was worth waiting for a more favorable moment to leave for the US. However, my chosen “mission” to show the achievements of Soviet art overseas and to speak of their artistic value seemed undoubtedly noble.

Did it have to be done 33 years after the collapse of the Soviet state? Without a doubt, yes! The jazz movement in a country shown back in 1926 as comprising “a sixth part of the world” is barely described in English, despite the fact that jazz in Russia celebrated its centenary in 2022. Russia’s contribution is inscribed in the world’s musical context, as my compatriots have achieved recognition both at home and abroad. Some artists born in the USSR — for instance saxophonist Igor Butman, trumpeter Alex Sipiagin, double bassist Boris Kozlov and pianist Vyacheslav Ganelin, who formed the avant-jazz trio Ganelin-Chekasin-Tarasov — can be considered jazz stars of the first magnitude.

This is not a recent phenomenon: In the late 1980s, Howard Mandel (now JJA president) wrote about the Ganelin trio’s American tour for The Washington Post, saying, “As any artists who play for an audience without defeating them, who trust the audience with their heart, these musicians say they hope for audiences who will not be wearing blinkers or reject what they offer.”

I achieved my coveted victory. I received the precious invitation that I needed to participate in the Fulbright program from North Texas University, located in Denton, Texas. It was like winning the lottery! The UNT is one of the world pioneers of jazz education. Since 1946, the One O’Clock Lab Band has been based there – as mentioned above, an orchestra with a glorious historical past, which has seven Grammy Awards® to its merit. Now this incubator of talents who come to Texas from almost all states is led by conductor and arranger Alan Baylock. His orchestra sounds highly professional, playing a diverse repertoire – from pieces by modern composers to the jazz tradition.

A similar educational model has been adopted in the Old World. I have worked at jazz festivals with The Bundesjazzorchester (BuJazzO, founded in Germany in 1988), and with the Academic Band jazz orchestra of the Gnessins Russian Academy of Music (launched in 2003) operating along the same lines. UNT Music College is of grand Texas scale: there are ten educational orchestras here – the Two O’Clock Lab Band, the Three O’Clock Lab Band, etc. Each has its own focus.

Having dealt with a weighty bundle of documents and taken a leave of absence from my jobs, I flew to the United States. It took 19 hours with transfers in Moscow and Istanbul. On January 6, 2024 Kimberly Hannon Teal met me at the Dallas-Fort Worth airport. It was already dark outside. We headed off to Denton, 42 miles from Dallas. Along the way we tried to buy a local SIM card and made an excursion of Denton’s historic center.

Kimberly warned me that for the UNT students the topic of “Soviet Jazz” is very exotic, and therefore there weren’t many people willing to attend my class. However, for a debutante, any audience has value. I was not displeased.

Throughout the semester students and I listened to themes by Soviet musicians, followed the evolution of jazz in the USSR, and explored the creativity of its key representatives – from the first experimental jazz orchestra by Valentin Parnakh in 1922 to collectives that arose in the late 1980s, during the era of perestroika and glasnost and survived in the post-Soviet period. It quickly became clear that many elements of Soviet life, so natural for Russia and completely uncharacteristic for the United States, required an explanation.

What is the Komsomol, the Palace of Culture? How do I correctly translate the contractions GosKoncert or LenGosEstrada? How does the Soviet jazz club differ from the American one? Sometimes I had to explain Soviet realities as if to the inhabitants of another planet, my listeners found them so unusual and incomprehensible. Even the performance of songs in Russian surprised them. Of course, I tried to convey the songs’ contents, to decipher the multiple Soviet acronyms, for instance CPSU – Communist Party of the Soviet Union or CHAW – The Central House of Art Workers, and many others.

The adoption of the word “estrada”, known in European languages in the meaning “an open street stage”, may be representative a number of my pedagogical successes. Since the late 1930s, thanks to the pioneer of Soviet jazz Leonid Utyosov, it has become synonymous with popular music in the Russian-speaking space. In the same sense, it is used by S. Frederick Starr, the American author of Red and Hot: The Fate of Jazz in the Soviet Union – 1917- 1980, the fundamental monograph in English on Soviet jazz. After several lectures and colloquiums in our class, “estrada” became part of the daily vocabulary.

Besides their vocabulary, the students’ perception of Soviet music also changed. As the music appeared to them as more complex, acquiring national features and intonational richness, it aroused their increasing interest. Over time, each student had his own Russian favorites: One admired the talent of multi-instrumentalist David Goloschekin, who plays ten(!) instruments; another was close to the fusion style of saxophonist Alexey Kozlov; the third found German Lukyanov’s compositional discoveries and his appeal to Russian folklore attractive. Of course, Russian names were a challenge for the Anglophone audience. Just try to say the name Goloschekin correctly and without pauses!

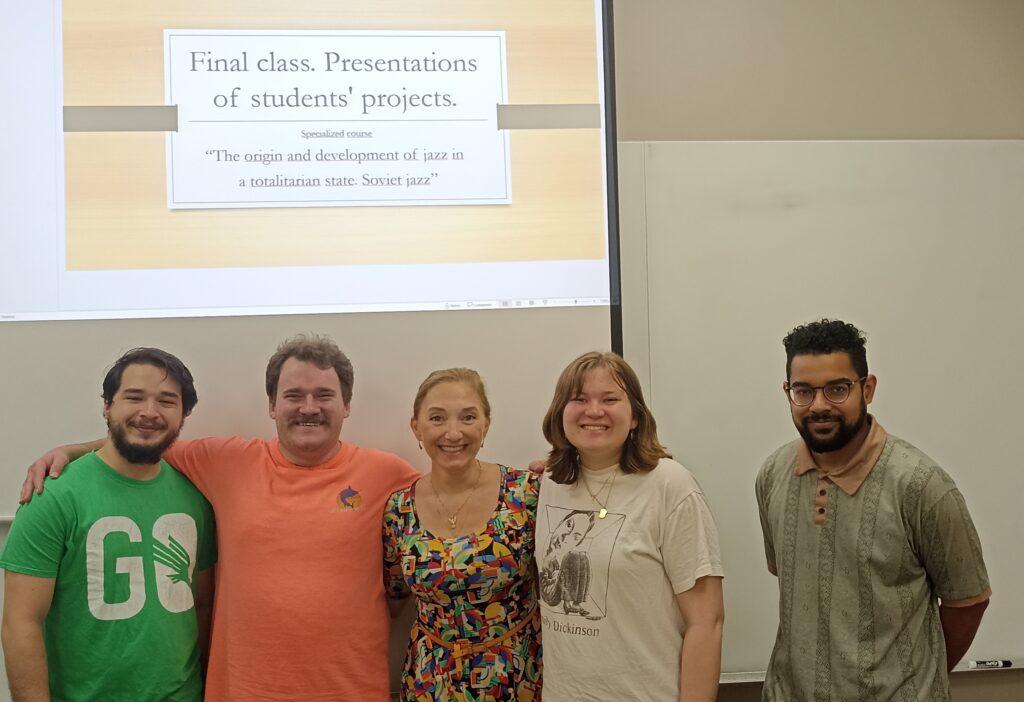

It is difficult to say now how useful this semester with a Soviet flavor was for the future professional lives of Lily, Garrett, Jacob and Nabil. But I know for sure that their horizons became wider.

And my horizons have been enriched equally. The creation of a new educational course always implies the relentless intellectual growth of its author. You never know which question you will need to answer in class. And besides that, during my free days and spring break I managed to travel and discover my America.

Throughout my trip, it was nice to remember that I could always return to Dallas. But I am fascinated by Chicago, New Orleans, Cleveland, Denver, Fort Collins and I love New York with all my heart. Each city gave me unique meetings, impressions and new friends.

In Cleveland, my dear “siblings” Oliver Ragsdale,Jr. and Brenda Terrell twice arranged for me a visit to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (for a teenager of the 1990s, this is almost a temple) and meet with the cultural community of the city. I could never have imagined that my humble persona and jazz in Russia could cause such great attention! In Chicago, Howard Mandel showed me the historic jazz and blues South Side, took me to a Monty Alexander concert at the Jazz Showcase and told me a lot of stories. In Dallas for a Herbie Hancock concert, I saw a total solar eclipse for the first time in my life.

Thanks to my participation in the Fulbright Environmental Seminar, in Fort Collins I made new friends and spent my birthday in Rocky Mountain National Park. Hot New Orleans boomed with a jazz festival, and New York, literally every minute brought new meetings and strong aesthetic experiences, including the Louis Armstrong House Museum; an exhibition and tour dedicated to the Harlem Renaissance; concerts by Dianne Reeves, Chucho Valdés and Joe Lovano, Kurt Rosenwinkel, John Davis and Boris Kozlov, Allan Harris; the Käthe Kollwitz exposition at MoMA, and walks around Manhattan with my friend the Russian trumpeter Kostya Gevondyan . . .

Will I miss all that? Don’t even ask. This experience turned out to be so exciting that I made a new promise to myself, set a new goal. Life moves on. I flew back towards Chelyabinsk on May 20.

Now that I’m at home and busy with concerts, tours, lectures, interviews, I can see that jazz in Russia is currently experiencing its Golden Age. A phrase from a song by the popular Russian singer Zhanna Aguzarova repeats in my head: “I recently visited a wonderful country . . .”

In fact, I still continue to discover my America, because this is the first article I have written for a foreign publication, my first attempt to reflect on my immersion in the jazz culture of the United States and my first experience as a jazz ambassador from Russia. Reflection is, as Confucius said, the way to knowledge.