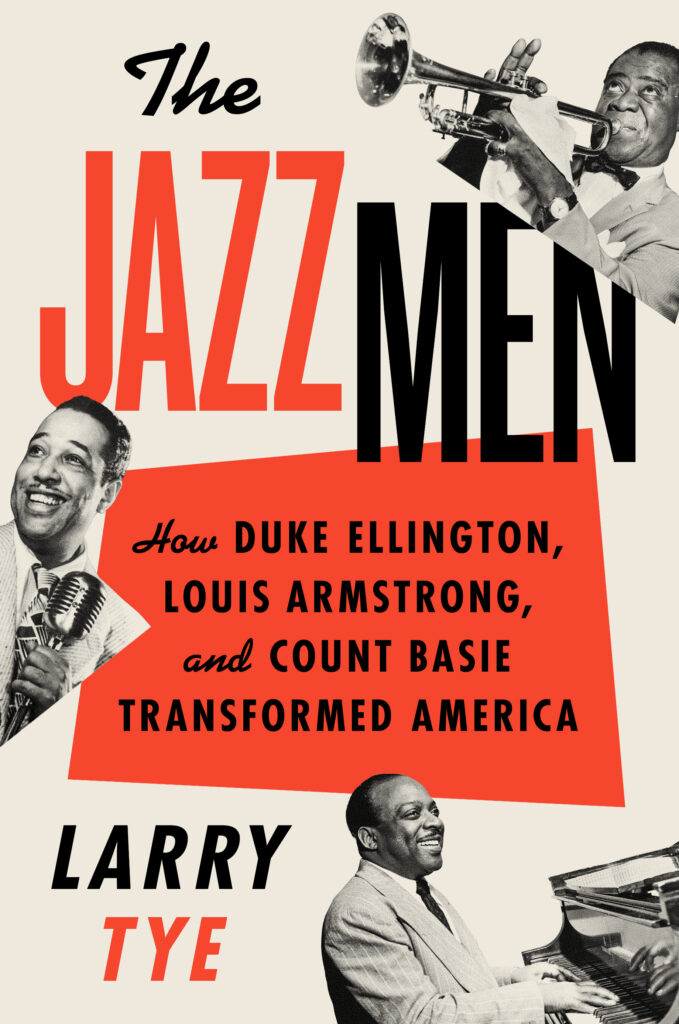

Insults couldn’t pierce the thick skin of musicians like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong or Count Basie, long accustomed to bigoted slurs and crude critique. But when reviewers blithely demeaned them as uncultured clowns, or savage beasts, something snapped

Armstrong “might have come straight from some African jungle and then, after being taken to a slop tailor’s for a ready made dress-suit, been put straight on the stage and told to ‘sing,’” Hannen Swaffer, one of Britain’s best-known drama critics, wrote in the Daily Herald in 1932. A competing London rag, the Daily Express, described Satchmo’s singing as “savage growling [that] is as far removed from English as we speak or sing it – and as modern – as James Joyce.”

Louis absorbed the attacks without publicly responding. He knew it was futile to take on journalists who bought their ink by the barrelful, and that even negative write-ups built his following. He’d grown up being told which urinals, schools and friends were off-limits to Negroes like him, and he knew his bid to break through to white audiences would open him to abuse. But it stung, and years later he explained that “when I was coming along, a black man had hell.” He boasted how he’d snapped back against one hateful reviewer: “I told that bastard, ‘You telling me how to blow my god damn horn and you can’t even blow your goddamn nose.’”

The racial condescension was by no means limited to Satchmo or to America. A year earlier, the Cleveland News’ Archie Bell said this of the Ellington Cotton Club Orchestra: “These chocolate-tinted folk have something distinctly artistic and fine to offer, when they adhere to their own idiom.” Even John Hammond, Basie’s enabler and a social crusader, reverted to racial stereotypes in trying to tell Black musicians like Ellington how to behave. “Ellington is fully conscious of the fact that Broadway has not treated him fairly, knowing many of the sordid details,” Hammond wrote in 1935. “And yet he did not lift a finger to protect himself because he has the completely defeatist outlook which chokes so many of the artists of his race.”

Duke delivered a titanic response with each new riveting composition telling the story of his race. While he preferred to speak through his piano and his orchestra, two years before Hammond’s rebuke, Duke told a Scottish journalist, “You have no idea of the fury with which people have attacked me through the press and by personal letters. One man wrote saying that as my music is at present it is an insult to the word.” Duke’s counter was that much the way bagpipes captured the spirit of Scotland, so “my contention about the music we play is that it also is folk music, the result of our transplantation to American soil, and the expression of a people’s soul.”

Basie also was occasionally singed by racist reviewers, although he took less flak than the other two because he maintained a lower profile in those early years and kept his focus on Black audiences and Black reviewers. Yet even the Count couldn’t escape Jim Crow’s strictures. At a 1938 faceoff at Madison Square Garden with purported King of Swing Benny Goodman, Basie and his band “practiced some plain and fancy carving at the expense of Benny Goodman’s reputation,” wrote reviewer George Avakian. Sadly, because he was Black and Goodman white, “Basie wasn’t even mentioned on the tickets and half the posters. He got $400 for the date. BG got $2,500.”

Basie’s response to the slights and the barbs was, as always, boiled down and low- pitched: “I learned a critic is nothing but a human being.”

Over the years, however, the professional critics softened to the point of being difficult to distinguish from adoring fans. Reviewers clutched for metaphors to describe Basie. He was a master at meshing egos, creating a communal blueprint. His rhythm section was “nothing less than a Cadillac with the force of a Mack truck,” while the Count himself was the best accompanist – and the most laconic. “The number one jazzman in the world today,” concluded one writer.

They showered similar accolades on Duke. “I could go on writing from now until the Judgment Day on the topic of Duke as a person and an artist, of the way he starts his numbers by rippling away at the piano until the band is set to go, of how he accompanies tap-dancers, of how his personality, as he sits in front of the band, expresses every mood of his own glorious music,” English composer and journalist Spike Hughes wrote in 1933, sounding decidedly different notes than his countrymen who a year earlier had maligned Armstrong as a “gorilla” and a “savage.” Thirty-six years later a US reviewer gushed, “Like motherhood, practically nobody is against Duke Ellington.”

As for Satchmo, in 1949 he became the first jazz musician to be splashed across the cherished cover of Time magazine, a publication that 17 years before diminished him as “a black rascal raised in a waifs’ home” whose “eyes roll around in his head like white, three-penny marbles.” Now it saluted him, delighting that “both jazz and Louis emerged from streets of brutal poverty and professional vice – jazz to become an exciting art, Louis to be hailed almost without dissent as its greatest creator-practitioner.”

Not all reviewers were smitten. Paul Eduard Miller wrote in 1941 that “Armstrong had chosen to play exclusively for the box-office.” Hammond had been even tougher on Ellington, saying his “music has become vapid and without the slightest semblance of guts.” And Leonard Feather would deliver this overly personal and thoroughly damning verdict on the Count: “What has happened to the Basie juggernaut illustrates a classical pattern: You start out making musical history by accident, and wind up making plenty of money by design. Somewhere along the way, sidemen get bored and quit the band, or worse, get bored and stay on.”

Ellington spoke for all three when he answered the attacks this way in a 1965 article in Jazz Journal: “If you find a beautiful flower, it is probably better enjoyed than analyzed, because in order to analyze it, you have to pull it apart, dissect it. And when you get through you have all the formulas, all the botanical information you need, and all the science of it, but you haven’t got a beautiful flower anymore.”