The breadth of jazz journalism is rapidly changing in the midst of existential cultural enlightenment and incremental improvements regarding the intense and complex Western and global racial climate. These changes are inviting the possibility of tonal journalistic adjustments and acknowledgment of the contributions of oppressed peoples, particularly Black women jazz musicians, composers and singers.

We cannot tell the true story of jazz without Black women and their intersectional experiences. The experiences, perspectives and resilience of Black women overcoming the dark barriers of racism and sexism to become success stories promises to brightly color the history of jazz, allowing critics, through this context, to deliver it more depth, examine different angles and untapped ways to address difficult issues within the jazz canon.

Black feminism has been brought to the fore of conversation, particularly, through the “This Is A Movement” symposium that took place January 15 – 17, 2022. Jazz community members from the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, M3 (Mutual Mentorship for Musicians), The New School, NYC Winter Jazz Fest and esteemed musicians such as Angel Bat Dawid and Georgia Anne Muldrow came together to explore jazz and gender through the Black feminist provocation. The convening, at the very least, opened the door for rumination of how Black feminism can be enfolded into the realities, perspectives and language of jazz professionals and the new generation of jazz artists.

There are few outlets, communities and organizations specifically dedicated to combat the limitations of male-dominated jazz journalistic writing outside of the tangible work of Women in Jazz Media (meaning it’s the only org specifically dedicated to this cause, focusing on journalism and criticism). It is understandable that white jazz critics may struggle with being told that their work is being considered incomplete after years of writing, but these disparities are not personal, they are systemic and it is important that there be an openness to the notion. If white men covered Black women as often and as passionately as male jazz musicians there would be no conversation. White men must accept that they could have done more and now is the time to reflect and engage. This is not about the past, it’s about the future and the future includes an in depth examination of Black women’s stories in jazz.

Any community or creative field that has a majority of people with the same background, race or creed will overlook the experiences of the minority, even if they do their best to cover other communities. Certain stories must come from writers who have shared similar experiences as their subjects. One cannot learn or buy empathy, it has to come from an authentic understanding and source of care that is immaterial.

So, of course, Black women should be commissioned to write more, but it is also important to search out Black women writers who are adept in political and theoretical works of Black feminism along with general cultural critics. It is important to be intentional about reaching out to Black feminists and offering journalistic opportunities to write about jazz. Their knowledge is rich and it will bring desirable results of evocative works that have never been written before.

With this said, it is also vital to ask the question how do all jazz critics and journalists embed Black feminist theory into their work? Journalists with any background can begin with research.

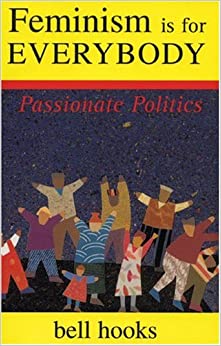

bell hooks’ Feminism Is For Everybody: Passionate Politics; bell, a

Black woman, gathers fodder and solutions in a broader race and gender, class, global feminism, marriage and reproductive rights. Her 1984 book Feminist Theory: From Margin To Center goes deeper into the specifics of Black feminist theory by directly challenging the whiteness of feminism and breaking down the presence of intersectional differences all feminists need to be aware of when pushing against oppression.

Other books to explore are Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality by Jennifer C. Nash, Black Feminist Anthropology by Irma McClaurin and Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins. And of course, the renowned author Angela Davis has been an incredible thought leader on feminism in Black music, including blues and jazz.

A specific and recent correlation to jazz can be gleaned from “Billie Was A Black Woman,” described as “a four-part podcast series that refracts Black womanhood through the prism of legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday.”

MORE RECOMMENDED READING

Corregidora, a novel by Gayle Jones

The Drum Is A Wild Woman: Jazz And Gender

In African Diaspora Literature, by Patricia G. Lespinasse

Constructing A Nervous System, a memoir by Margo Jefferson

Bebop-Rebop, a novel by Xam Wilson Cartiér

Jazz Fan Looks Back, poems by Jayne Cortez

I Put A Spell On You, the autobiography of Nina Simone

Why should jazz critics and journalists consider learning about Black and intersectional feminism? What does it have to do with covering straight-ahead jazz or writing reviews and features about people who aren’t Black women?

Any source of knowledge is going to bring interesting context to articles. A journalist who covers international politics cannot ignore elections and war in second and third-world countries if they do not want to be limited in the work they acquire. A jazz journalist who cannot intelligently write about the (many) plights of Black women cannot cover women in jazz in the way they deserve, and in the way readers deserve.

We must share what we’ve learned and challenge ourselves to face disparities head-on in order to keep up with the world around us. And the world around us is asking for us to acknowledge, listen to, learn from and to write fair, thoughtful and thorough analyses of Black women in jazz.